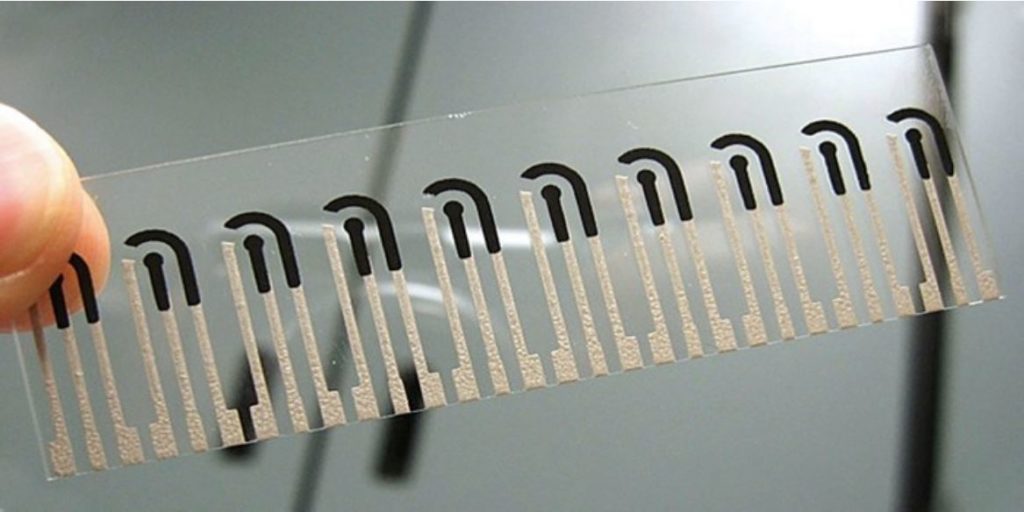

We’ve helped to develop a sensor strip that provides a rapid, low-cost screening tool for detecting fentanyl. Image: University of California, San Diego.

Are you a Netflix subscriber? Have you watched the series Dirty John? If you have, you might know about the drug fentanyl. ‘Dirty John’ Meehan, the criminal and con artist, secretly steals fentanyl from the hospital where he works. He becomes addicted to the drug that, as a nurse anaesthetist, he’s supposed to provide to his patients.

Skip forward to 2019, and fentanyl is fuelling the opioid epidemic here in Australia. Aside from its health impacts on users, there is evidence to suggest that increased exposure could put our ambulance officers and other first responders at risk. So, together with the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), we’ve helped to create a new way to detect fentanyl in the field, where it’s needed most.

Fentanyl: fuelling a worldwide opioid epidemic

Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine, and it’s misuse is having serious consequences in Australia.

Fentanyl is a highly-addictive prescription chronic pain killer, and acute analgesic. It’s 50 to 100 times more powerful than morphine. It’s inexpensive to make and easily combined with other drugs, making it a prime candidate for misuse. And if you get the dosage wrong, this highly potent drug is a killer.

Fentanyl has now become the leading cause of drug overdose deaths in the United States. And here in Australia, there has been an alarming increase in the number of accidental fentanyl-related deaths in recent years. Deaths from fentanyl increased 1800 per cent in 15 years in Australia. The drug was listed in Australia’s Annual Overdose Report as a major factor driving a rapid increase of accidental opioid-related deaths since 2011. This surge in use was confirmed by a 2018 national wastewater drug monitoring program.

In 2002, a fentanyl analogue aerosol was used to subdue a Moscow hostage situation. It resulted in 125 people accidentally dying from exposure to the drug.

All of this also means an increase in fentanyl exposure for ambulance officers, paramedics, police and other front-line personnel who respond to drug-related situations. There is evidence that first responders could face a moderate risk of harm through direct contact with the substance, so safety is a concern.

How will fentanyl-sensing strips help?

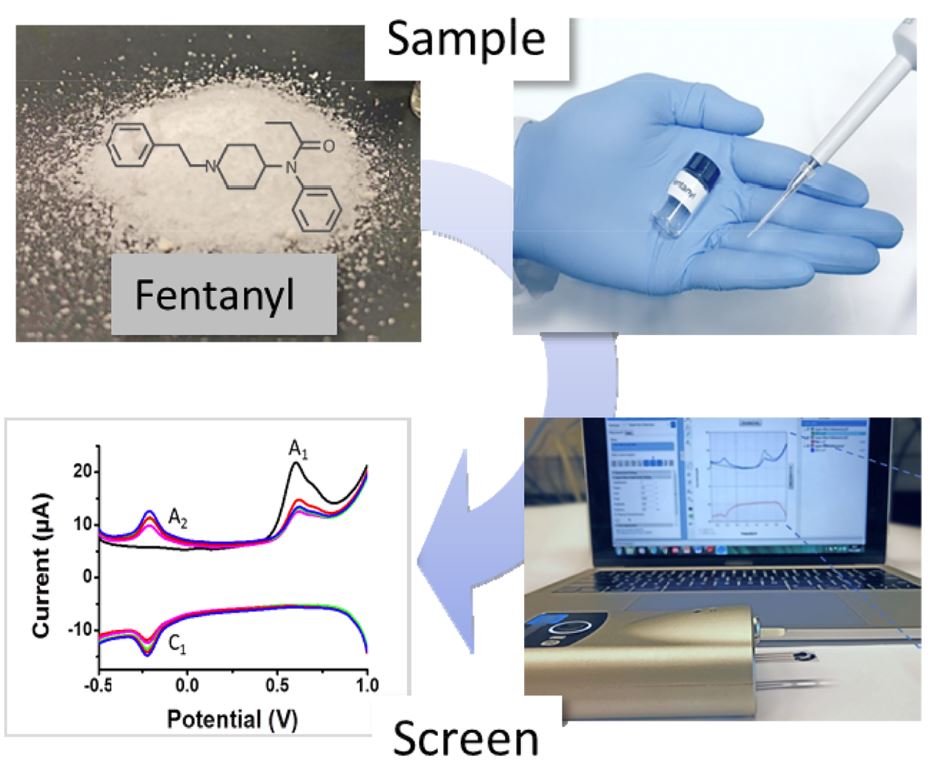

In breaking news, we have worked with UCSD to help create disposable electrochemical strips that detect the presence of fentanyl.

Traditionally, fentanyl detection has happened in a forensic lab. That’s time-consuming and requires expensive equipment. Having a portable fentanyl detecting system means first responders can quickly and safely identify what they’re dealing with on the spot, and react accordingly.

This technology helps first responders to identify whether a person/object has been in contact with the most miniscule amounts of fentanyl. In fact, we have the technology to pick up low micromolar concentrations of fentanyl in common cutting agents found in illicit drug formulas like heroin.

What’s the science behind the speedy sensor strip?

The individual disposable sensor strips are about 3 x 1cm. They look a little like a transparent sheet of stamps, with ten sensors printed per strip.

The sensors’ electrodes are screen-printed onto polyethylene terephthalate sheets, using ink embedded with carbon or silver/silver chloride. The carbon working electrode is treated with a stabilising room temperature ionic liquid which helps attract fentanyl to the electrode surface.

Next, the electrochemical strip analyses the chemicals in the sample. How? The strip measures the electric currents produced by its various compounds as they undergo oxidation or reduction processes, building a distinct electrochemical fingerprint. The strips are fed into a hand-held device for “on-the-spot” sample analysis, with results displayed within a minute.

The fentanyl sensing strips developed in collaboration with the University of California, San Diego, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL), and Imperial College London, take fentanyl detection out of the lab and into the field. Image: Analytical Chemistry (ACS Publications).

This is the first time electrochemical detection has been used to detect fentanyl. Compared to current methods, it provides a fast, cheap way to test for fentanyl in the field, when first responders need it most.

We’ve helped develop the strips through a multi-country, multi-agency collaboration. We worked with researchers from the University of California, San Diego in the USA, the Defence Science and Technology Laboratory (DSTL) and Imperial College London in the UK.

Remember Snow White and the lab-on-a-glove?

When we last left our friend Snow White, she and the seven dwarves were headed to their local bar to celebrate a foiled attempt on her life. The wicked queen’s evil plot to kill Snow White with a poisonous apple had been thwarted, thanks to our ingenious lab-on-a-glove: a device that detects toxic chemicals on the spot.

The team behind lab-on-a-glove is the same team who developed fentanyl testing strips, another particularly useful technology used by Snow White and the dwarves when the wicked queen, out on bail, managed to track them down and spike their drinks. The tech-savvy friends were once again prepared, making sure to test their drinks before consumption, and demonstrating once again that ‘love’s first kiss’ is no match for science when it comes to dodging acute analgesia.

1st April 2019 at 7:33 pm

You have a typo in the third paragraph, should be fentanyl not fentalyl.

2nd April 2019 at 9:25 am

Thank you for letting us know Urmila. We have fixed this accordingly.

Cheers,

CSIRO Social Media Team