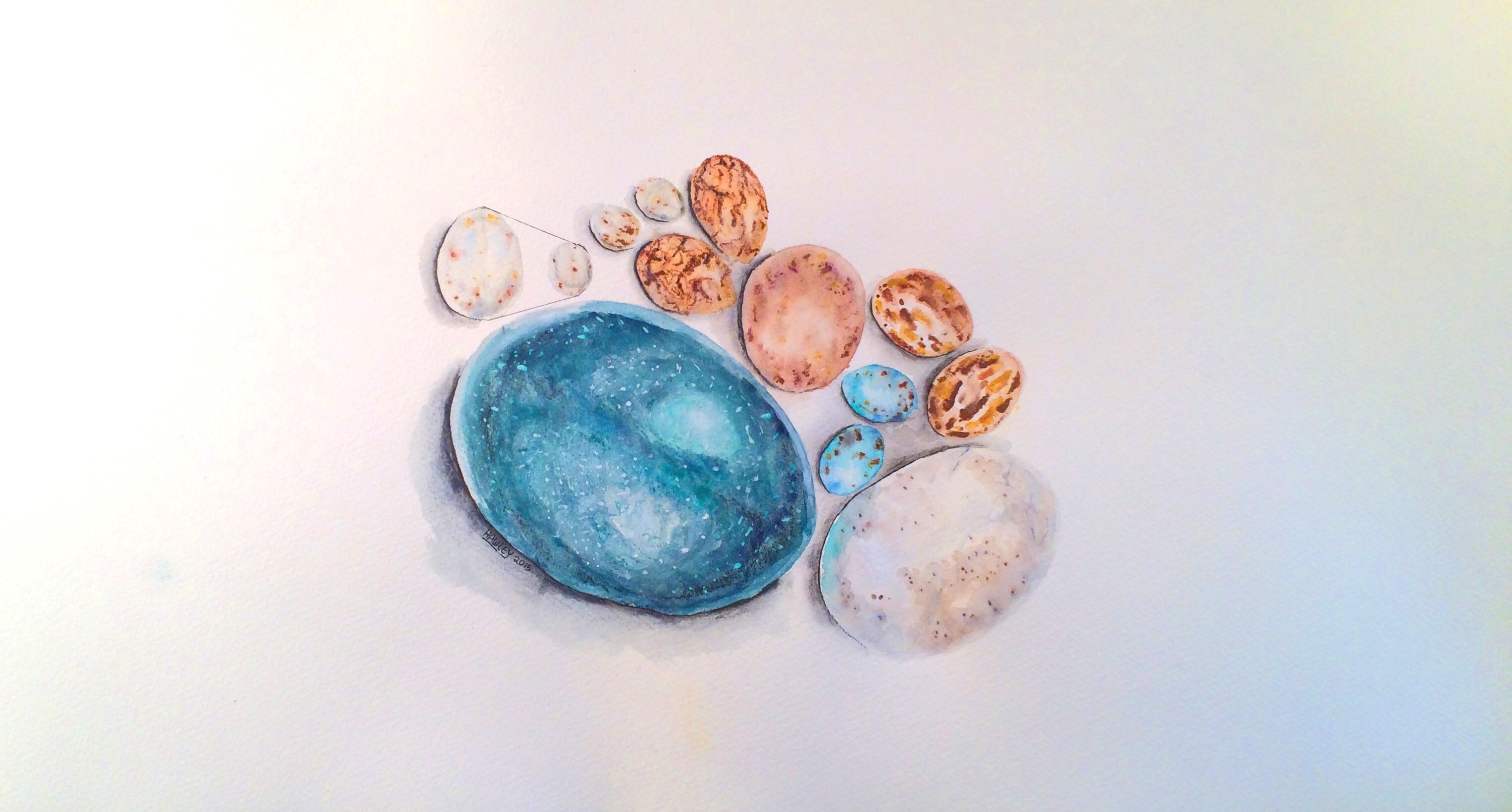

Get in my belly. Flickr: Allison Marchant

By Indra Tomic and Leo Joseph

Five whole days. This seems to be the maximum time that lapses between gold tinsel and Christmas crackers and the onslaught of chocolate Easter eggs beckoning you at every turn at the supermarket. White chocolate eggs, dark chocolate bunnies and chocolate filled with toothache-inducing gooey caramel. They’re everywhere, looking so darn fine and totally irresistible.

But it’s not just supermarket eggs that look darn fine. Nature pulls out all the stops when it comes to real eggs – the kind that hatch and create life.

Now whilst birds are the most commonly thought of animals that lay eggs, there are lots of other vertebrate animals that also lay eggs, from reptiles, to sea creatures and even some mammals. And just as different species of animals tend to look different to us in terms of their physical appearance, so too are their sounds, nests and even eggs.

For birds their egg shape is determined by a number of inter-related factors ranging from the bird’s natural history through to the shape and size of its pelvis. However, not all animal eggs take on the familiar shape of the chicken’s egg – they can be spherical, oval, long and elliptical and some not even egg shaped in the slightest.

Eggs of birds are either uniform in colour or patterned. Some eggs are pale blue, others green or dark brown, but it is fair to say that most birds’ eggs have a ground colour that is some shade of white, blue or brown, and can be patterned with speckles, spots or stripe like effects.

Eggs, glorious eggs.

So, why are eggs so important?

Eggs are a remarkable form of life and provide us with invaluable information, such as:

- the animal’s breeding biology

- patterns in how animals’ relationships have evolved

- the environmental pollutants at the time

- and how some birds’ eggs mimic other birds’ eggs.

Animals breeding records

First and foremost, an egg is a superb record of where a species was breeding at a particular point in time. A clutch of eggs is connected to a geographical location and a particular day, month and year – all of which can be linked to the overall climate and weather of that place at that time of the year. So, if we want to understand how environmental change will affect the reproductive cycles of birds, particularly migratory species that cover long distances, then the higher the quality of information that we can put into predictive models, the better our chances of getting higher quality and more meaningful results from those models.

Patterns of relationships

Another reason eggs are so important is their ability to help us understand patterns of relationship among closely related species. A few years ago we uncovered an unexpectedly close relationship of a bird that occurs only in Tasmania and which has the rather old-fashioned English name of Scrub-tit (scientifically known as Acanthornis magna). For many years bird experts had considered it to be a close relative of the scrubwrens, which are the species of the genus Sericornis. In fact it looked so much like a scrubwren that it was sometimes considered to be a member of that genus.

When we analysed the DNA sequences of both of these birds and their relatives, we learned that Acanthornis was in fact most closely related to a group of three species called whitefaces. Whitefaces live in semi-arid and indeed in some of the most arid deserts in mainland Australia, obviously nowhere near Tasmania and are in the genus Aphelocephala. After checking that no mistakes were made back in the lab, we also noticed that the eggs of Acanthornis, were actually rather distinctive in shape and patterning and a little more like those of whitefaces than of scrubwrens.

- Whitefaces eggs. Image: Atlas of Living Australia

- Scrubwren eggs. Image: Atlas of Living Australia

- Scrubtit eggs. Image: Atlas of Living Australia

Environmental pollutants

Eggs are also useful records of environmental pollutants. Because egg collections represent long time-series, they have been invaluable in determining at what point in time various pollutants began to accumulate in food-chains.

Eggs were a critical part of research that uncovered the adverse effects of the insecticide DDT. Museum collections of the eggs of raptors, such as Peregrine Falcons, showed that the eggs were becoming thinner over time. Research eventually showed that this was because DDT in the environment was becoming concentrated up the food chain and was reaching highest concentrations therefore in top predators such as birds of prey. Thinner eggshells meant that the eggs were more prone to breaking, leaving theembryos to die and so raptors were experiencing steep and rapid declines in their populations.

Evolution indicators

There are some birds, such as cuckoos and some finches that lay their eggs in the nests of other birds, leaving them to be cared for and raised by the bird host. These birds are called brood parasites. Depending on factors such as whether the host species’ nest is an open cup or a dome-shaped nest having a concealed nesting chamber, some brood parasites have eggs unlike those of their hosts whereas others have evolved egg patterns that are almost indistinguishable from the host’s own eggs.

Can you spot the imposter? (A: The cuckoo egg is on the right in each of these clutches.)

Flickr: Royal Society / Claire Spottiswoode, Dorothy Hodgkin

All of these research eggs-amples would not be possible if museum collections, such as our own Australian National Wildlife Collection, had not invested time and resources into building and storing egg collections.

Our collection is filled with all sorts of eggs from soft-shelled eggs of lizards, snakes and turtles to hard-shelled eggs such as birds and crocodiles, each of them special and unique, containing a tremendous source of data just waiting to be ‘cracked’ and provide another vital clue to be analysed, whether for distributional and migrational studies of birds, or as indicators of evolution, or as records of environmental pollutants.

Here’s a few of our favourites from the collection:

So, spare a thought for the 20,000 clutches of wonderful little real-life eggs in our collection this weekend, as you chomp through tens and tens of chocolate ones. Ours may not give anyone a sugar-high but they unlock mysteries in the world around us – and that makes them sweeter than chocolate.

2nd April 2015 at 10:17 am

Brava Anna Maria. Interesting to read effects of pesticides such as DDT. Pity scientists have to find and prove the adverse effects of such items after the harm is already in our food chain.

31st March 2015 at 6:51 pm

Molto interessante l’argomento, l’uovo è la vita, per questo è il simbolo della Pasqua, che vuol dire rinascita.