And at night the wond’rous glory of the everlasting stars – Banjo Paterson.

Photo: James Gilbert, Australian Astronomical Observatory. More sizes

It’s a long way from from Potsdam, Germany, to Coonabarabran, NSW: 15,781 kilometres, in fact.

Yes, it’s a long way to come for a Saturday night party. But Matthias Steinmetz thought it worth the trip. Last week he flew to Australia for just such an event.

But why?

Potsdam, Germany (left) and Coonabarabran, NSW (right).

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Matthias Steinmetz – that’s Professor Matthias Steinmetz to you – is the Director of the Leibnitz Astrophysical Institute at Potsdam.

For the past decade he’s also headed up a nine-country collaboration that set out to get the personal details of almost half a million stars: their brightness, colour, and distance; how fast they move and in what direction.

From all that, astronomers can work out how old these stars are, where they came from, and how they’re related.

And that’s the key to unlocking the history of our Galaxy.

The project is called RAVE, the radial velocity experiment.

Among much else, RAVE has found a ‘dwarf’ galaxy swallowed by our own Galaxy, like a rat swallowed by a python. It’s detected how the Galaxy wobbles. And it’s re-weighed the Galaxy.

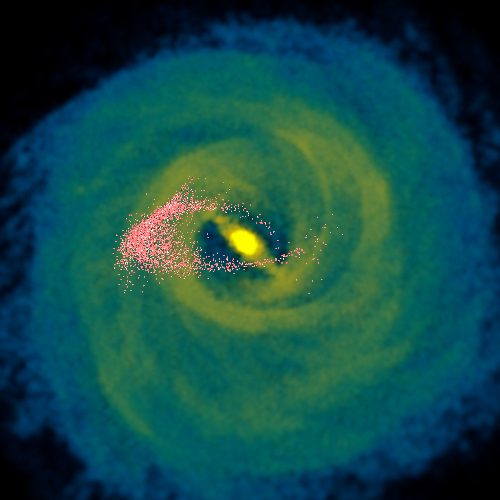

The "Aquarius stream": the stars of a dwarf galaxy swallowed by our own Milky Way galaxy.

Visualisation:

The “Aquarius stream”: stars of a dwarf galaxy swallowed by our own Milky Way Galaxy, identified by the RAVE team. Visualisation: Arman Khalatyan, AIP

This grand enterprise has been taking place at Siding Spring Observatory, 25 km from Coonabarabran.

Siding Spring Observatory: back in business after the fire of January 2013. Photo: Iraklis Konstantopoulos

The actual business of getting the data has been carried out by a few Australian astronomers and their robot sidekick, 6dF.

6dF stands for Six-Degree Field, which is the size of the chunk of sky the system can see. In astronomy terms, it’s big. (For comparison, the Moon is half a degree across.)

The 6dF robot picks up optical fibres with its pneumatic gripper and places them precisely on a metal plate that goes into the telescope. Each fibre is positioned to catch the light of a single star.

The telescope itself is the venerable UK Schmidt, operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory (AAO).

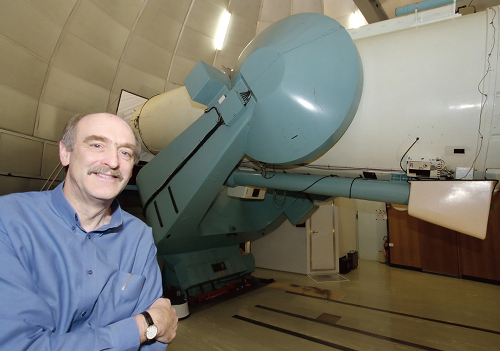

Dr Fred Watson with the UK Schmidt Telescope.

Photo: Shaun Amy

Dr Fred Watson with the UK Schmidt Telescope.

Photo: Shaun Amy

Last Friday the AAO’s Fred Watson, Project Manager for RAVE, switched off the 6dF robot and hung up his optical fibres for the last time.

And on Saturday they all drank to the Universe and its glory.

Professor Matthias Steinmetz cuts the cake at the post-RAVE party. Photo: David Malin