A simple geological classification of whisky.

What do our scientists do in their spare time? Paul Shand’s expertise lies in geology and hydrogeochemistry, and he’s discovered the ‘water of life’ – whisky that is – among the rocks.

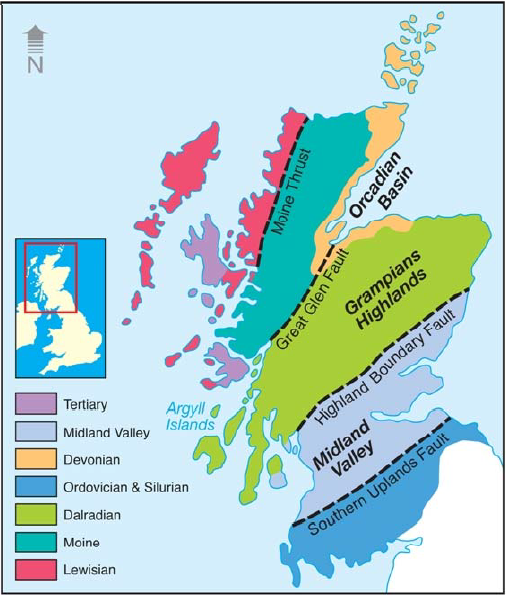

Paul is a scientific whisky buff; working to reclassify whisky according to geology. The simple classification used at present is based on numbers of distilleries in a region along with old political divides. This weekend, Paul is aiming to convince the Malt Whisky Society of Australia’s 4th Whisky Convention that geology is a much better way to classify whisky.

The link between geology and whisky

Geology’s influence on whisky is mainly due to its control on water chemistry. The chemistry of the water is believed to influence the taste of the final product. There’s little research in this area but there is a wealth of experience from seasoned distillers. Paul mentioned that the old timers certainly thought there was an effect from water chemistry, and since they developed the distillation techniques through trial and error it would be wise for us to listen. The importance of water chemistry is also a view of the people on site who actually make the whisky, but there is debate as some companies agree while other multinationals and writers don’t think it has an effect.

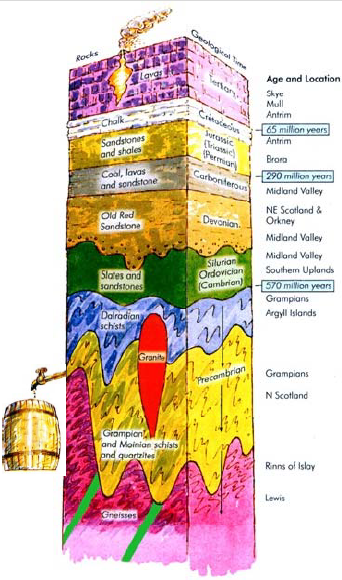

Essentially Scottish malt whisky contains components of the landscape, dissolved in the water via interactions with the bedrock and soil through which it has passed. Each sip contains part of that geological history which comes from the rocks ‐ it may be hundreds of millions of years old, it may be only a few thousand – that’s worth savouring and contemplating. We’ll drink to that, whether it’s a Devonian or Precambrian drop.

The whisky geological column. From Cribb & Cribb, 1998.

In search of the perfect dram

Paul was brought up in Wick in Scotland, and walked past the renowned Pulteney distillery on the way to school each day. He subsequently studied geology at Edinburgh University before completing a PhD on ancient volcanic rocks in the south of Scotland.

His baptism into malt whisky happened during an exploration for gold in the Scottish Highlands, where he not only discovered solid gold, but also sampled ‘liquid gold’ for the first time after a hard day of digging. He then worked for 15 years with the British Geological Survey travelling extensively in search of the perfect dram but under the pretense of research on ‘water for life’.

Paul Shand with a glass of liquid gold.

It was during a sabbatical to Australia that Paul found exciting scientific challenges and some of the world’s best Uisge Beatha, Gaelic for ‘water of life’. So he stayed, taking up a position as Principal Research Scientist in our Water for a Healthy Country Flagship. He is also an adjunct Professor in the School of the Environment at Flinders University.