It’s 1970: The Partridge Family’s I think I love you is tearing up the charts. Bell-bottoms are all the rage, and in just a few years the first Motorola mobile phones and Apple computers will hit the shelves. As computing technology begins its journey of ubiquity into everyday life, the world’s reliance on advanced technologies is reaching all-time highs.

In this brave new world it’s becoming increasingly important to protect rooms full of sensitive mainframe computers, telephone switches and circuitry from fires. As the world becomes more reliant on technology, solutions are urgently being sought to prevent infrastructure disturbances that might lead to debilitating technology outages.

An image of the original Very Early Smoke Detector Apparatus system (VESDA)

The original Very Early Smoke Detector Apparatus system (VESDA), detecting fire fast enough to prevent technology outage disaster!

A bright spark

Meanwhile, in the bushland of Western Australia, a team of our researchers, including researcher/pilot David Packham, are investigating forest fires using an aircraft and a sophisticated piece of technology called a nephelometer. Commonly used to detect air pollution, nephelometers use scattered light to measure suspended particulates in sampled air, detecting combustible particles like smoke and even gases at extremely low particle concentrations (to 0.005 per cent) down to molecular size.

Across the country, on a separate mission to thwart Australian infrastructure service interruption, Len Gibson and John Petersen from the Postmaster-General’s Department (PMG) are searching for suitable smoke detecting technologies. Their fire safety investigations lead them to our very own bushfire detection team in Perth. Len Gibson, a pilot like Packham, arranges a secondment to the WA bushfire research group.

Flying with Packham through some of the largest forest fire plumes ever deliberatively lit for research, Gibson has a ‘light bulb moment’ when he witnesses how highly sensitive the nephelometer is to smoke – and immediately sees application in his PMG telecommunication facilities.

Smoking hot technology

Off the back of a fruitless search for commercially available fire prevention technologies for telephone equipment, the PMG team looks to our work with the nephelometer and decide that applying the outdoor technology to this indoor challenge may be just the ticket!

After a number of false starts on the path to commercialisation, in 1978, the collaborative team meets Martin Cole, Managing Director of the Melbourne based electronics company IEI Pty Ltd. The team devise a way of sampling airflows in air-conditioning systems using multi-holed pipes to capture and filter air before testing it for smoke using the nephelometer’s sensitive sampling and detection system.

Voila! The first commercial version of the Very Early Smoke Detection Apparatus, VESDA, is born.

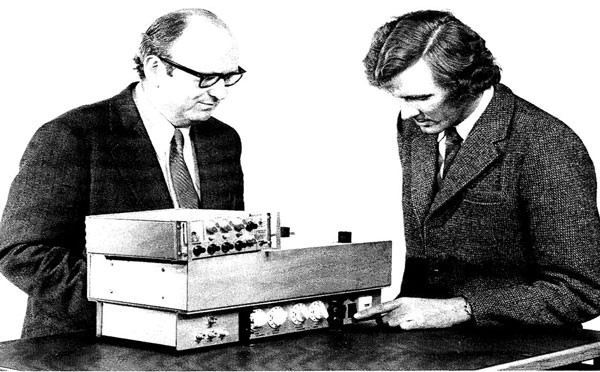

A black and white photo of two scientists with an early model smoke detector

Len Gibson and David Packham with an early version of VESDA.

In the 40-plus years since its development, the technology has been enhanced to incorporate solid-state electronics, laser-light sources and more sophisticated diagnostics systems. Our relationship with this Australian technology is ongoing. The owners of VESDA (Xtralis) remain our customers today and we continue to test their products for compliance to Australian and International standards.

Aspirated smoke detection systems have become the preferred technology for early smoke detection in telephone exchanges, data centres and industrial control rooms around the world. They play a vital role in asset protection and business continuity as well as providing safety protection for workers.

Smoke (no longer) gets in your eyes

Recently David Packham, John Peterson, Martin Cole and Len Gibson (posthumously) were awarded The DiNenno Prize, which is better known as the ‘Nobel Prize for public safety.’

Congratulations to all the team members honoured for their achievement with this truly collaborative innovation!

6th February 2018 at 2:53 pm

Hi Mike,

CSIRO is proud of its history in relation to aspirating smoke detectors, and enjoy working with numerous companies who develop and manufacture them today. We even the early porotypes shown in the photo in this article in our meeting room to show them to visitors.

It is quite certain that modern aspirating detectors are very sensitive to incipient stages of smouldering fires, such as might occur in overheating electronics. However, their use in high sensitivity ranges in a residential home would be rather impractical. They are well renowned for responding to smoke generated from remote locations, such as bushfires occurring many many kilometres away. This may not be surprising given that their initial development was to aid in the identification of bushfires!

While mass production on a scale comparable to smoke alarms, say, might lead to some simplification and efficiencies, ASD are naturally quite complex and also require a level of maintenance that would be hard to imagine being provided in a typical residential application.

Additionally, their use of a sampling pipe system would be difficult to accommodate in a typical residence. Admittedly there are now systems available that use flexible tubes rather than rigid piping, but the complexity at the detector would seem to overwhelm any possible advantages.

27th January 2018 at 2:24 pm

A very interesting article and well done to the inventors and the CSIRO involvement.

There is currently a lot of debate about which type of smoke detector alarm should be fitted in Australian domestic residences, namely Ionisation and Photoelectric technology – so why isn’t an Aspirated system in the frame? Is it a cost issue or is it because it is not deemed necessary.

There contradiction between the the two systems currently in use – one is designed to detect a ‘raging’ fire quicker than the other which is quicker at detecting a slowly smoldering fire – some states have made one type mandatory whilst other states have the other type mandatory. Would not a mass produced commercially competitive Aspirated system for residential use do the job of both of the units currently in use?

cheers,

Mike