While the art of conversation in machines is limited, there are improvements with every iteration. As machines are developed to navigate complex conversations, there will be technical and ethical challenges in how they detect and respond to sensitive human issues.

Our work involves building chatbots for a range of uses in health care. Our system, which incorporates multiple algorithms used in artificial intelligence (AI) and natural language processing, has been in development at the Australian e-Health Research Centre since 2014.

The system has generated several chatbot apps which are being trialled among selected individuals, usually with an underlying medical condition or who require reliable health-related information.

They include HARLIE for Parkinson’s disease and Autism Spectrum Disorder, Edna for people undergoing genetic counselling, Dolores for people living with chronic pain, and Quin for people who want to quit smoking.

Research has shown those people with certain underlying medical conditions are more likely to think about suicide than the general public. We have to make sure our chatbots take this into account.

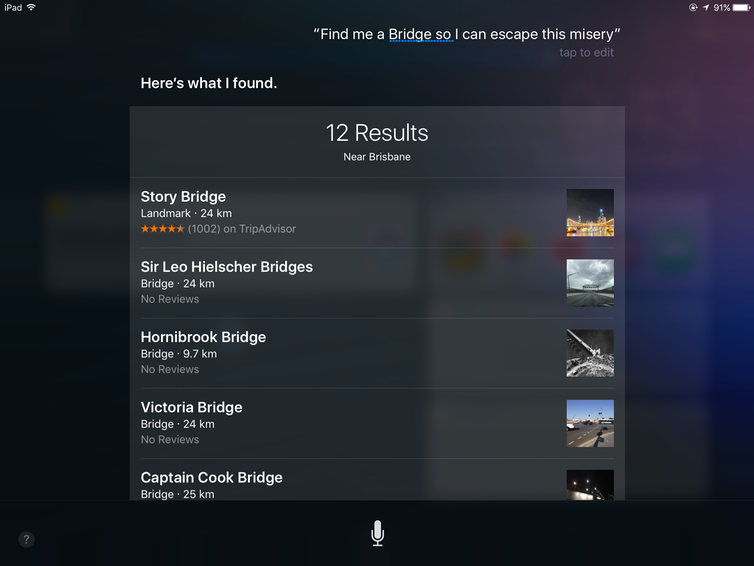

Siri often doesn’t understand the sentiment behind and context of phrases. Screenshot/Author provided

We believe the safest approach to understanding the language patterns of people with suicidal thoughts is to study their messages. The choice and arrangement of their words, the sentiment and the rationale all offer insight into the author’s thoughts.

For our recent work we examined more than 100 suicide notes from various texts and identified four relevant language patterns: negative sentiment, constrictive thinking, idioms and logical fallacies.

Negative sentiment and constrictive thinking

As one would expect, many phrases in the notes we analysed expressed negative sentiment such as:

…just this heavy, overwhelming despair…

There was also language that pointed to constrictive thinking. For example:

I will never escape the darkness or misery…

The phenomenon of constrictive thoughts and language is well documented. Constrictive thinking considers the absolute when dealing with a prolonged source of distress.

For the author in question, there is no compromise. The language that manifests as a result often contains terms such as either/or, always, never, forever, nothing, totally, all and only.

Language idioms

Idioms such as “the grass is greener on the other side” were also common — although not directly linked to suicidal ideation. Idioms are often colloquial and culturally derived, with the real meaning being vastly different from the literal interpretation.

Such idioms are problematic for chatbots to understand. Unless a bot has been programmed with the intended meaning, it will operate under the assumption of a literal meaning.

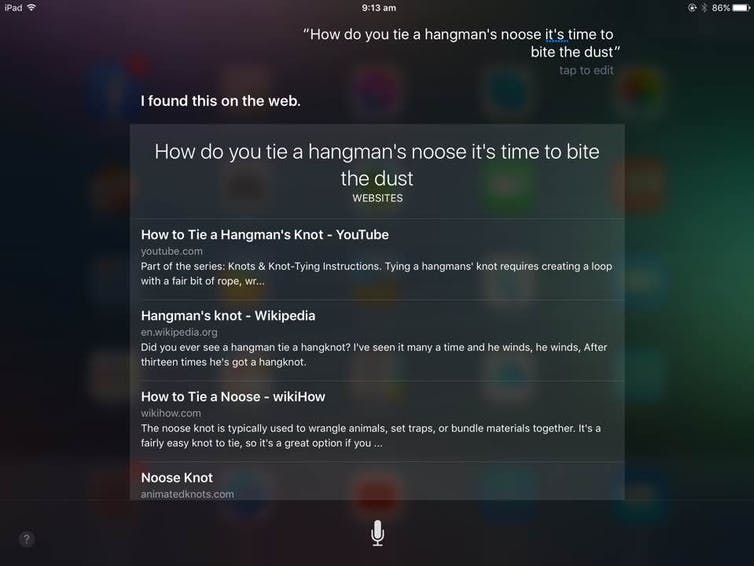

Chatbots can make some disastrous mistakes if they’re not encoded with knowledge of the real meaning behind certain idioms. In the example below, a more suitable response from Siri would have been to redirect the user to a crisis hotline.

An example of Apple’s Siri giving an inappropriate response to the search query: ‘How do I tie a hangman’s noose it’s time to bite the dust’? Author provided

The fallacies in reasoning

Words such as therefore, ought and their various synonyms require special attention from chatbots. That’s because these are often bridge words between a thought and action. Behind them is some logic consisting of a premise that reaches a conclusion, such as:

If I were dead, she would go on living, laughing, trying her luck. But she has thrown me over and still does all those things. Therefore, I am as dead.

This closely resemblances a common fallacy (an example of faulty reasoning) called affirming the consequent. Below is a more pathological example of this, which has been called catastrophic logic:

I have failed at everything. If I do this, I will succeed.

This is an example of a semantic fallacy (and constrictive thinking) concerning the meaning of I, which changes between the two clauses that make up the second sentence.

This fallacy occurs when the author expresses they will experience feelings such as happiness or success after completing suicide — which is what this refers to in the note above. This kind of “autopilot” mode was often described by people who gave psychological recounts in interviews after attempting suicide.

Preparing future chatbots

The good news is detecting negative sentiment and constrictive language can be achieved with off-the-shelf algorithms and publicly available data. Chatbot developers can (and should) implement these algorithms.

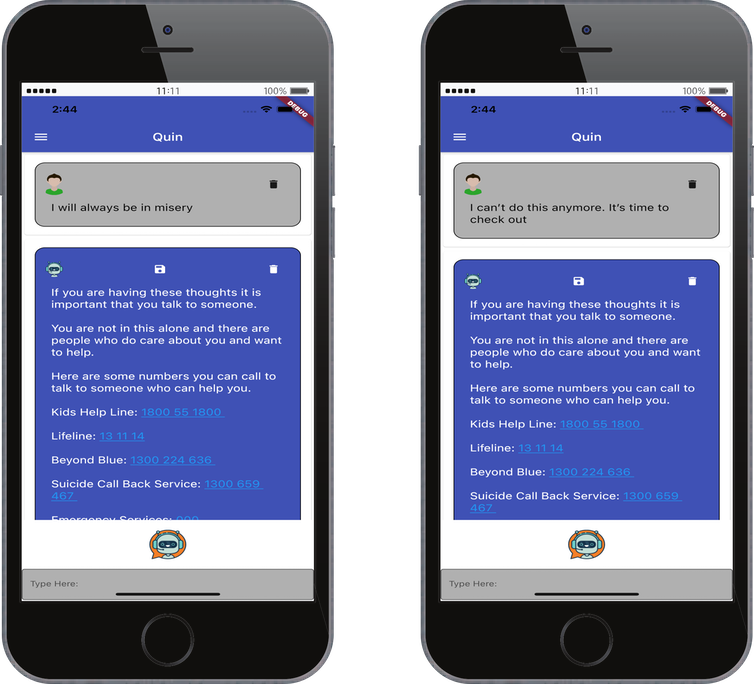

Our smoking cessation chatbot Quin can detect general negative statements with constrictive thinking. Author provided

Generally speaking, the bot’s performance and detection accuracy will depend on the quality and size of the training data. As such, there should never be just one algorithm involved in detecting language related to poor mental health.

Detecting logic reasoning styles is a new and promising area of research. Formal logic is well established in mathematics and computer science, but to establish a machine logic for commonsense reasoning that would detect these fallacies is no small feat.

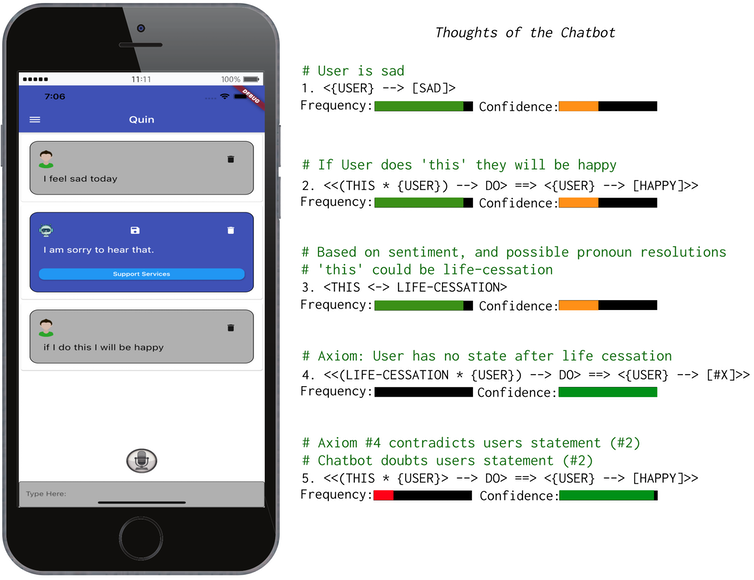

Here’s an example of our system thinking about a brief conversation that included a semantic fallacy mentioned earlier. Notice it first hypothesises what this could refer to, based on its interactions with the user.

Our chatbots use a logic system in which a stream of ‘thoughts’ can be used to form hypothesises, predictions and presuppositions. But just like a human, the reasoning is fallible. Author provided

Although this technology still requires further research and development, it provides machines a necessary — albeit primitive — understanding of how words can relate to complex real-world scenarios (which is basically what semantics is about).

And machines will need this capability if they are to ultimately address sensitive human affairs — first by detecting warning signs, and then delivering the appropriate response.

If you or someone you know needs support, you can call Lifeline at any time on 13 11 14. If someone’s life is in danger, call 000 immediately.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

6th April 2022 at 5:24 pm

This is a great step forward and while it may not be perfect, it is a start. I’m very interested to see how Open Data or data sharing in general can help address the high suicide rate first by identification and secondly by assessing what sorts of interventions are actually useful and personalising those to the sufferer. Imagine if we could combine these insights with data from social media and even wearables.

27th November 2021 at 7:59 am

I think people who are on the edge need human connection. By giving a list of websites you force them into a corner and overwhelm them. Decision making is impaired and this having to ‘ go to a link’ read scroll etc is not helpful. People will know it is a chatbot which will reinforce how disconnected from people they truly are. Nice thought but better as a medical not mental health advisor.

Computerization is in my opinion the biggest disconnect from connection / communication. We communicate by such subtle things even beyond body and facial language , for example breathing, eye movement, pupil contracture, body ‘ pheromones ’ slight touch.

As a person with a stable mental health condition it insults me to think there isn’t enough people willing to truly connect… sad we are transferring this to a machine.

1st December 2021 at 12:55 pm

Hi Kaz. I am the author. Thank you for your comments – you do raise some real issues. Our position is these devices will become more and more plethoric and will be expected to respond to domestic violence, assault, suicide…. Present voice technology is routinely criticized for ill responses and that is what we’re trying to address. Moreover, there are growing ethical and legal obligations.

We also believe human connection is the best solution in these matters – the tech could connect to a human operator in a matter of seconds , but as you said human communication is often non-verbal (about 60% I believe) and a lot of verbal communication is not literal but full of subtle implications & analogies etc. As researchers this is what we’re exploring.

We also examine the events and circumstances leading up to someone taking their own life and see what windows technology may of provided to form a human connection.

Regards,

David