We’re counting down some of our top 2020 science moments. This includes Airthena, a technology that pulls carbon dioxide from the air to put bubbles in your beer.

To say 2020 has been ‘quite a year’ is possibly the understatement of the year.

Many of our scientists have been working on you-know-what. However, most have been going about their work making sure CSIRO delivers practical solutions to real issues and challenges through innovative science and technology.

So, we decided to bring together some of our top 2020 science moments you may have missed.

Here’s cheers!

In February, we raised our glasses after finding a way to pull carbon dioxide (CO2) out of the atmosphere and put it into beer and other beverages.

In partnership with industry, we developed and trialled technology known as Airthena. It uses tiny sponges known as metal-organic frameworks (MOFs). They’re crystals with huge applications.

Essentially these MOFs suck the CO2 out of the air. As a result, Airthena can capture and recycle two tonnes of CO2 a year.

“As it requires just air and electricity to work, Airthena offers a cost-effective, efficient, and environmentally-friendly option to recycle CO2 for use on-site, on-demand,” our project lead, Dr Aaron Thornton said.

Bonus: it can be scaled up for commercial production. So you may see more atmospheric beers coming your way.

Window to a clear solar future

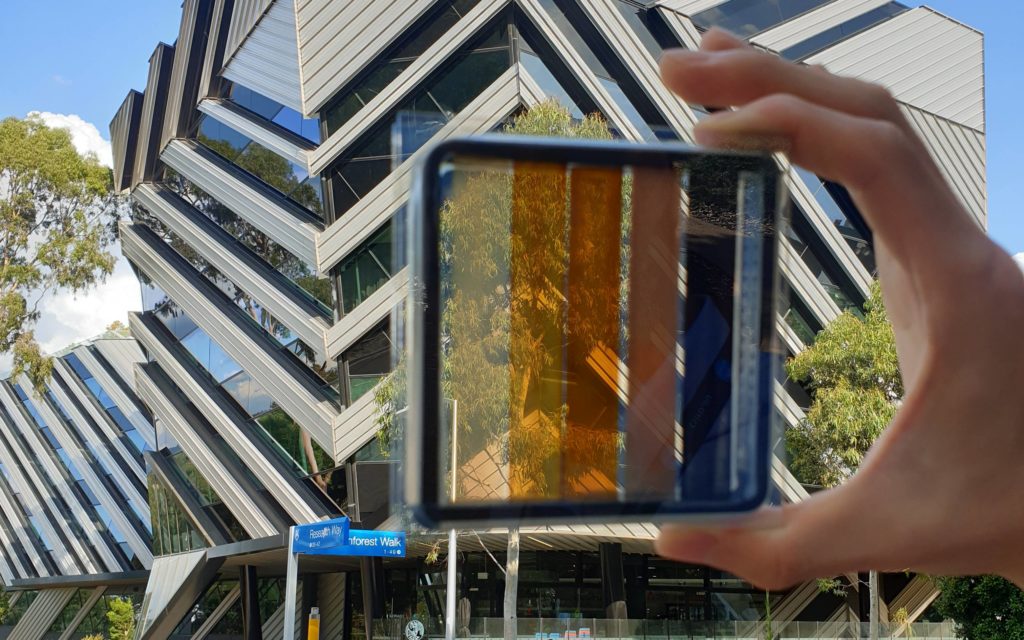

We created windows that will soon generate electricity! Or rather, semi-transparent solar cells that can be incorporated into window glass.

Amazingly, two square metres of this solar window will do the same job as a standard rooftop solar panel.

We did this alongside the ARC Centre of Excellence in Exciton Science (Exciton Science) and Monash University. Additionally, Viridian Glass, Australia’s largest glass manufacturer is now working on how the new technology could be built into commercial products.

Here it is! It’s a semi-transparent perovskite solar cell with contrasting levels of light transparency. Image: ©Dr Jae Choul Yu.

Cool coral

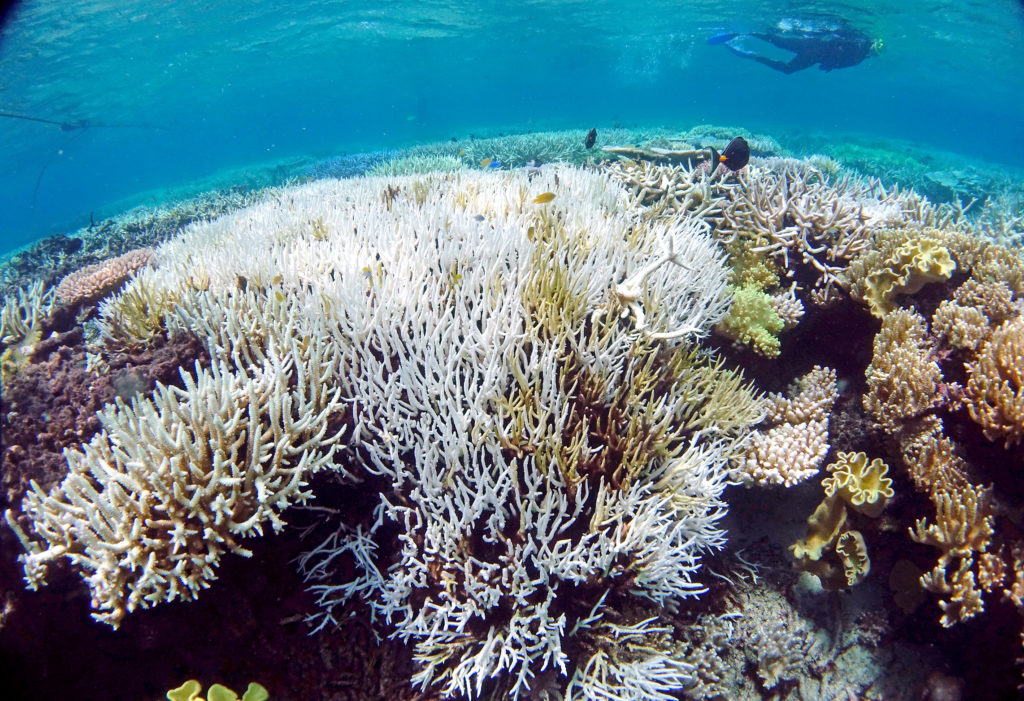

More good news on the environment front. A team of scientists successfully produced a lab-grown coral that is more resistant to increased seawater temperatures.

This potentially reduces the impact of reef bleaching from marine heatwaves. We were able to do this by boosting the heat tolerance of its microalgal symbionts, which are tiny cells of algae that live inside the coral tissue.

We helped develop this alongside the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) and the University of Melbourne.

Here’s what coral looks like when it’s gone through extensive heat stress. As a result, it’s lost their important algal symbiont, which supplies most of the coral’s nutrition through photosynthesis. Image: Chris Jones.

Move ’em on, head ’em up

Real space cowboys will swing into the saddle with this! More than 1000 feral buffalo and unmanaged cattle roaming Northern Australia will be tagged and tracked by satellite using our research.

The herd-tracking program uses GPS-tracking tags attached to the animals’ ears and delivers real-time, geographically-accurate insights into herd density, accessibility, and transport costs.

The animals will be tracked across a combined area of 22,314 square kilometres. The area covers the Arafura swamp catchment in Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory. It also covers Upper Normanby and Archer River on Cape York Peninsula in Queensland.

The program aims to turn the destructive pests into economic, environmental and cultural opportunities for Indigenous communities across the region. Additionally, it aims to create new best practice for managing large herds using space technology.

Even sponges have a nasty side

Marine scientists from Queensland Museum and the University of Munich have discovered the world’s largest number of new species of carnivorous sponges. And they did so from a single deep-sea expedition off the Australian east coast!

The scientists made the discovery while on board our RV Investigator.

Most sponges are filter feeders, which means they suck out passing plankton or nutrients in the water. But carnivorous sponges have evolved as predators and instead catch and digest their prey directly.

Previously, only three species of carnivorous sponges were known in Australia. As a result of this discovery, there are now 20.

How can you not find half the Universe?

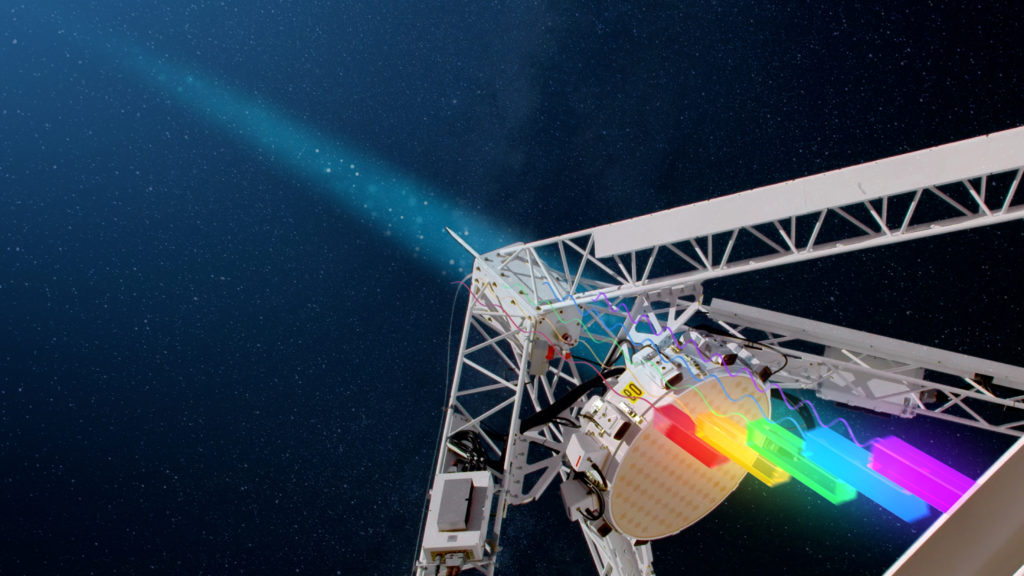

Our astronomers solved a decades-old mystery of ‘missing matter.’ It was long predicted to exist in the Universe but never detected.

Our scientists detected 50 per cent of the missing matter. All thanks to fast radio bursts (FRBs), defined as brief flashes of energy, that appear to come from random directions in the sky and last for just milliseconds.

Another key to finding the missing matter was our Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) radio telescope in Western Australia.

ASKAP has both a wide field of view, about 60 times the size of the full Moon, and can also image in high resolution. When the burst ‘arrive’ at the telescope, it records a live-action replay within a fraction of a second. It enabled scientists to determine the location of the fast radio burst to the equivalent of the width of a human hair held 200m away.

The radiation from fast radio bursts gets spread out by the missing matter in the same way that you see the colours of sunlight being separated in a prism. Scientists measure the distances to the fast radio bursts to determine the density of the Universe.

ASKAP radio telescope measures the delay between the wavelengths of a fast radio burst. This allows astronomers to calculate the density of the missing matter in the Universe. Image: ICRAR and CSIRO/Alex Cherney

The good oil

Omega-3 fatty acids are important for good health. They assist with brain and eye development and cognition, particularly in early childhood. They may also help to decrease the risk of cardiovascular diseases, neural disorders, arthritis, asthma and skin diseases in humans.

Omega-3 oils traditionally come from wild fish stocks and ocean krill. But minor sources are from nuts and seeds, and oils from flaxseed, soybean and canola.

Our new technology cultures and extracts omega-3 from specific strains of unique and endemic thraustochytrids, a marine microorganism.

We are working with Brisbane-based company Pharmamark Innovation to develop omega-3 oils, proteins and bioactives from marine microorganisms.

Name that species

From June 2019 to June 2020, our scientists gave scientific names to 165 new species. They included tributes to Marvel characters Deadpool, Thor, Loki, and Black Widow.

Deadpool is a fly whose namesake is the iconic comic character. Why? “It’s an assassin with markings on its back that resembles Deadpool’s mask,” entomology student and comic artist Isabella Robinsond said.

“I chose the name Humorolethalis sergius. It sounds like lethal humour and is derived from the Latin words humorosus, meaning wet or moist, and lethalis meaning dead.”

Deadpool fly (Humorolethalis sergius) has markings on its back that resemble Deadpool’s mask.

Capturing a comet

One of our biggest hits of the year was when the livestream camera on our RV Investigator captured an extremely bright meteor. It crossed the sky in front of the ship and then broke up over the ocean.

The bridge crew spotted the bright green meteor about 100 kilometres south off the Tasmanian coast. Consequently, they reported the sighting to the science staff on board the ship.

The ship was in the area to undertake seafloor mapping of the Huon Marine Park for Parks Australia, conduct oceanographic studies and run sea trials for a variety of marine equipment.

Top Aussie scientist

And topping off a big year for the national science agency, our Chief Scientist, Dr Cathy Foley will be Australia’s Chief Scientist in 2021.

Cathy, a physicist, has been with us for about 36 years. She began as a research scientist, working in manufacturing and eventually become our Chief Scientist in 2018.

As our Chief Scientist, Cathy led the development of a Quantum Technology Roadmap for Australia. It champions emerging and future areas of science research and capability within CSIRO. She has also been a high-profile and inspiring advocate for science and STEM careers.