Colour is one of those stunning everyday phenomena we take for granted, that we don’t stop to appreciate. Not only do we see colour every day, but essentially every day colours are all we see. To try and rattle you in your boots and wake you up to the subjective beauty of colour and the wonder of it as known through science, Questacon’s opened a new exhibit — Colour: See the world in a new light.

To add a six-legged facet to the exhibit, our National Research Collections have contributed some of the phenomenal diversity of colourful insects, and the myriad ways they use those colours: mimicry, warnings, and camouflage. Speaking of taking colour for granite, Geoscience Australia are also contributing colourful geological specimens to the exhibit.

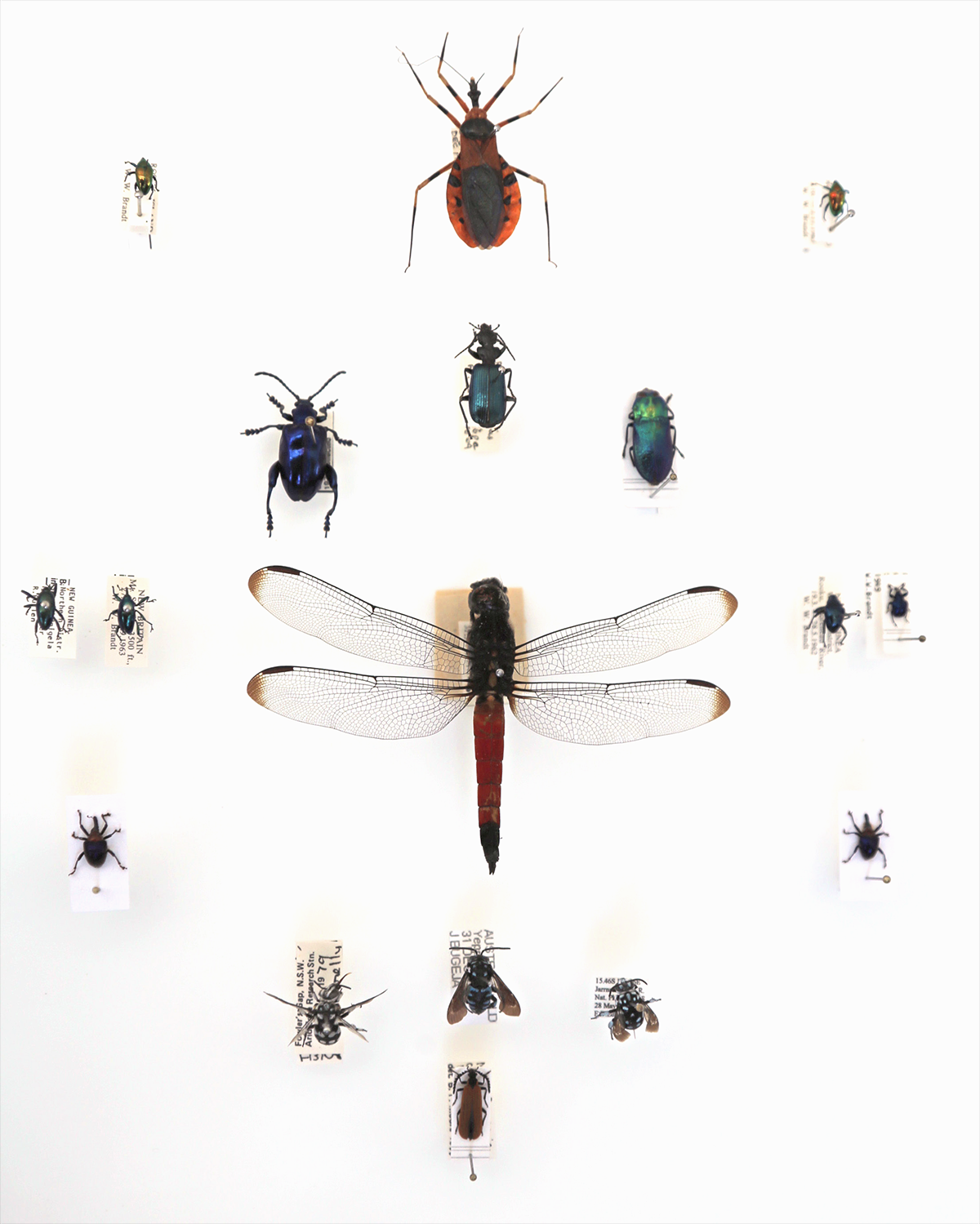

Here are some of the vibrant (and sometimes mute and coy) insects you’ll see when you visit the exhibit:

Butterflies? No, moths. Normally ‘drab’, moths like these Australian species (Miliona queenslandica, Agarista agricola) are active in the daytime so have re-evolved colours to warn away predators.

40% of insect species are beetles. The source of their wonderful iridescence lies in their wing coverings, ‘elytra’, which have structures in tight stacks that scatter incoming light, reflecting it in the rainbows you see above.

“Pigment molecules in these Australian Christmas beetles (family Scarabaeidae) are corkscrew-shaped, twisting the light they reflect (circular polarisation). We can use a mirror to reverse the direction of this twist. The filter absorbs light that twists in one direction, but not the other. The beetles’ colour is blocked while their reflection remains colourful.”

Fruits and berries are often brightly coloured to attract animals (like us) to eat them. But this certainly isn’t always the case. In fact, it’s often quite the opposite, called ‘aposematism’ meaning ‘sign for away’, where these brightly coloured insects are toxic to eat. Featured: beetles, true bugs, bees, and a centre-piece dragonfly.

“Insects mostly attract mates with chemical signals—not colours. However males and females can be coloured differently for other reasons. These are Australian Priam’s birdwing butterflies (Ornithoptera priamus). The male uses its green colouration to hide in the treetops where it spends its time. The female uses colour to dazzle predators—it is hard to keep track of in the dappled light of the rainforest understory. This tactic is also used by shoals of fish and herds of zebra.”

“These are weevils (family Curculionidae) from Australia and nearby islands. Their colours come from tiny iridescent scales, which contain structures similar to those found in opals. Weevils are the only insects in which this is known to happen.”

Unbeelievable: “These insects are mimicking (pretending to be) wasps and bees. Most of them are tasty food for predators but have independently evolved effective disguises.”

Want to take a peek inside our other collections?

The National Research Collections Australia are a vital resource for conservation and science. The collections underpin research in agriculture, biosecurity, biodiversity and climate change and are used by researchers all over the world.