Milking tarantulas may help to rid sheep of gastrointestinal parasites, a problem that costs our Australian sheep industry $400 million a year.

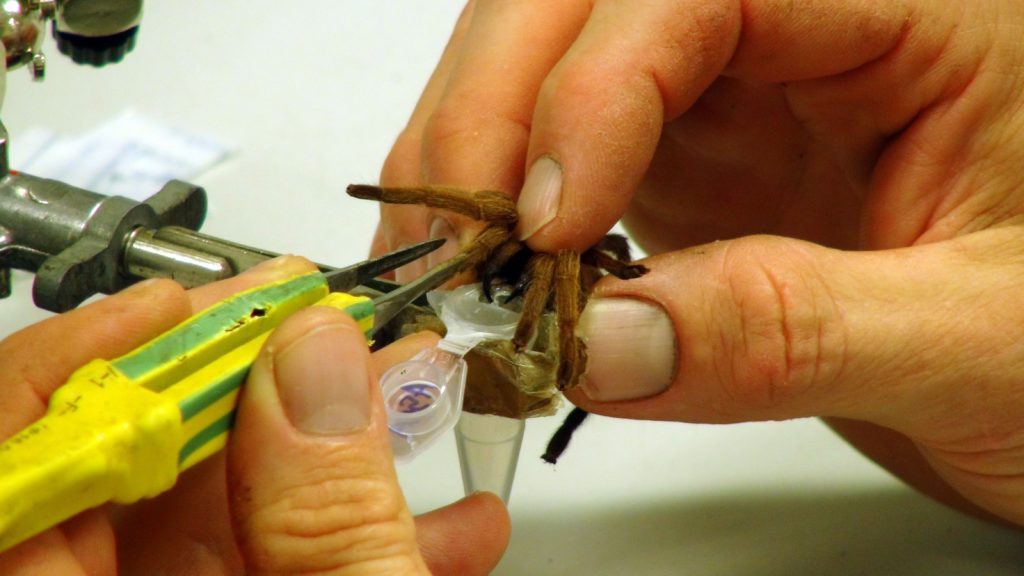

Just another day in the lab, milking a tarantula.

Cards on the table: if you’re squeamish this is going to be a difficult read.

Gastrointestinal parasites cost the Australian sheep industry around $400 million each year in treatment costs and lost productivity, with huge implications for animal welfare. The most common way of de-worming Australia’s more than 67 million sheep is by “drenching” them. No, that doesn’t mean cold-shocking the worms with the Ice Bucket Challenge. Instead, it’s a quick drug dose that’s delivered orally.

But the huge problem facing our farmers is that most worm populations are now showing resistance to the drugs which are used, making it more and more difficult to cure infections. This drug resistance is leading our scientists to work with The University of Queensland’s Institute for Molecular Bioscience (IMB) to look for new treatments derived from the venom of animals such as spiders, scorpions and assassin bugs.

Candy canes can spell death for sheep

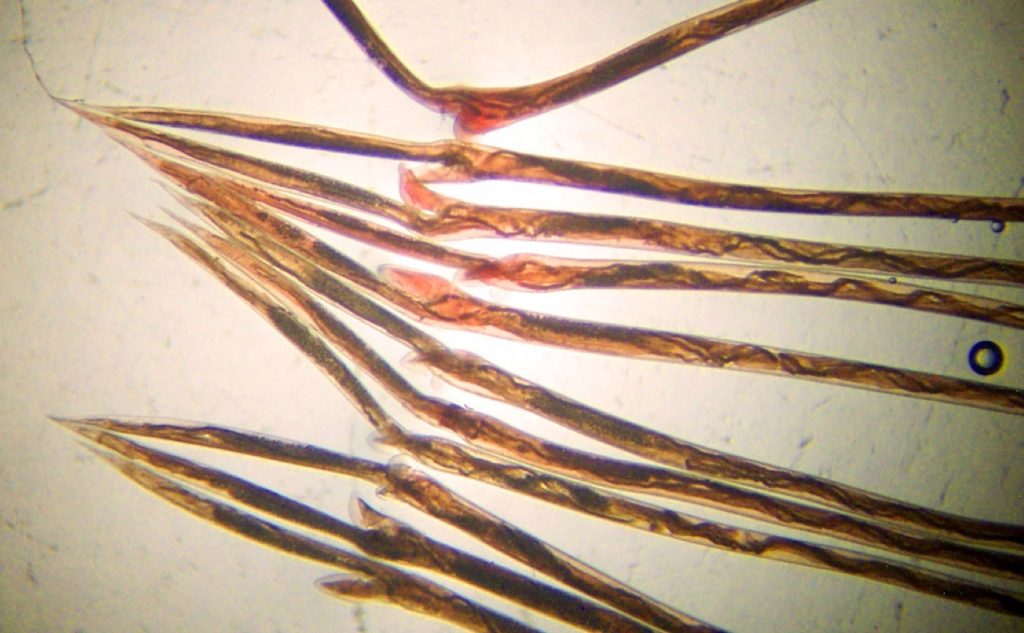

The Barber’s pole worm is named after their curly blood-filled intestines, which look like a red and white candy cane barber’s pole. Cute? No. Image: Peter Hunt.

Our very own Samantha Nixon, UQ PhD student and Westpac Future Leaders scholar is studying the effect of the venom from all things nasty on another particularly shady character – the Barber’s pole worm (Haemonchus contortus). A blood-feeding gut worm by trade, the Barber’s pole worm is a sheep’s worst nightmare.

Although these worms are relatively small (three centimetres in size) compared to tapeworms in sheep, which can be over a metre in length, Samantha says it’s the sheer number of the candy cane lookalikes that can overwhelm a sheep’s body.

“The number of adult worms in a sheep’s gut can be as high as 10,000, and these worms can actually drain 10 per cent of the sheep’s blood each day. If that happened to you, you can imagine that you would feel very ill,” Samantha explains.

This can quickly become a fatal spiral for a sheep’s health. They end up anaemic, malnourished and very weak, and can rapidly lose weight. Sudden death can occur if the infection remains untreated.

“From an animal welfare perspective, these parasites are absolutely devastating. From a farmer’s perspective, the loss of productivity is huge. You have drastic reduction in the quality and quantity of wool and meat, which really hurts the industry,” she says.

The good news is that spider venoms contain powerful chemicals that could be used to fight these infections.

Fighting the creepies with the crawlies

Venoms are an amazing untapped resource to look for potential drugs, having evolved over millions of years to deliver fine-tuned, potent and fast-acting chemicals.

Unfortunately though, drug discovery is a time-consuming process. The average drug takes more than 10 years to go through the process of discovery and testing before being released onto the market. The process is no different for Samantha’s work, though she had to overcome a fear of spiders just to get started.

“First we milk the venom, and then purify it before testing the crude venom against the parasite. Then we go back and forth between fractioning the venom and testing it to pick out the bioactive molecules,” she says.

“We’re looking to find individual molecules that work against the parasite, and only then can we start looking at how to produce them on a large scale.”

Factory farming venom out of animals like spiders isn’t feasible (not to be confused with the potential for farming spider silk from spider goats), so to develop a cost-effective drug you would need to create such a molecule at mass scale using methods like protein expression.

The hope is that such a drug would be effective against multiple types of parasites, not just the sheep’s arch-nemesis – the Barber’s pole worm. The drug might also be effective in other livestock like cattle, and even in people.

“When we find potential drug candidates, we will collaborate with researchers around the world to look for new ways they could be used. We want to make a genuine difference in the lives of people and animals affected by parasitic diseases,” Samantha says.

We're improving animal health and welfare.

22nd May 2021 at 11:38 am

Any plans to apply solutions to infected native fauna? Would be great to have Samantha’s ‘photo up here too. Women in successful roles in STEM – always great to hear about. Well done Samantha!

18th July 2018 at 1:57 pm

I presume all these parasites entered the country in the guts of the introduced sheep originally & have since spread to native fauna, ie. Kangaroos & wallabies, hence the anecdotal state of these species corpses

10th August 2017 at 4:11 pm

and I thought milking goats, sheep and cows by hand was a skill!