The litters of some species of sharks may share multiple fathers. We studied how frequently this occurs in two species of sharks caught by fisheries in Papua New Guinea and are using the information to help identify populations at risk of decline.

A photo of a grey reef shark swimming

We used DNA analysis in our multiple paternity study and found grey reef shark litters have more than one father.

From lizards that practise virgin birth, to birds that attract mates by displaying pretty objects and insects that eat their partners head first, breeding strategies in the animal kingdom offer endless variety.

In a recent study of sharks caught by fisheries in Papua New Guinea (PNG), a team of researchers looked at a breeding strategy called multiple paternity, which occurs when a litter of baby sharks has more than one father. Such litters are made up of both full and half siblings.

“We think multiple paternity might have advantages for both male and female sharks,” says Madi Green, a PhD student at the Australian National Fish Collection and the University of Tasmania.

“For males, it increases their opportunities to mate and sire offspring. For females, it increases the genetic diversity within a litter. For both sexes, multiple paternity might also help counteract the risks of inbreeding if the population is small and isolated,” she says.

Some shark species practise multiple paternity, while some are monogamous. Others can even reproduce by parthenogenesis, giving birth to offspring that develop from unfertilised eggs. Multiple paternity is thought to be more common in species whose females can store sperm after mating for later use, and in species that gather together at breeding time, which increases the number of available mates.

“The extent to which multiple paternity occurs in sharks is a bit of a mystery,” says Madi. “Solving it is important for conservation. Like most marine species, we can’t easily count sharks. Instead we estimate numbers using information like data from fisheries and exploring changes in the DNA of individuals within a population. Knowing the extent of multiple paternity helps us calculate that.”

Madi and the team measured multiple paternity in two species of sharks that are caught by fisheries in PNG, the grey reef shark, Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos, and the scalloped hammerhead, Sphyrna lewini. The sharks in the study were caught on-board commercial fishing vessels in the Bismarck and Solomon Seas.

“We took tissue from 11 pregnant females and their pups and used microsatellite markers, which are short repeating DNA sequences, to determine whether the pups in each litter were full or half siblings,” she says.

“We now know that multiple paternity is common in these two species. All five litters of scalloped hammerheads included half siblings, with an average of 17.2 pups per litter sired by between two and eight different fathers. Four of the five litters of grey reef sharks included half siblings, with a much smaller average litter size of 3.3, fathered by between one and three different males,” she says.

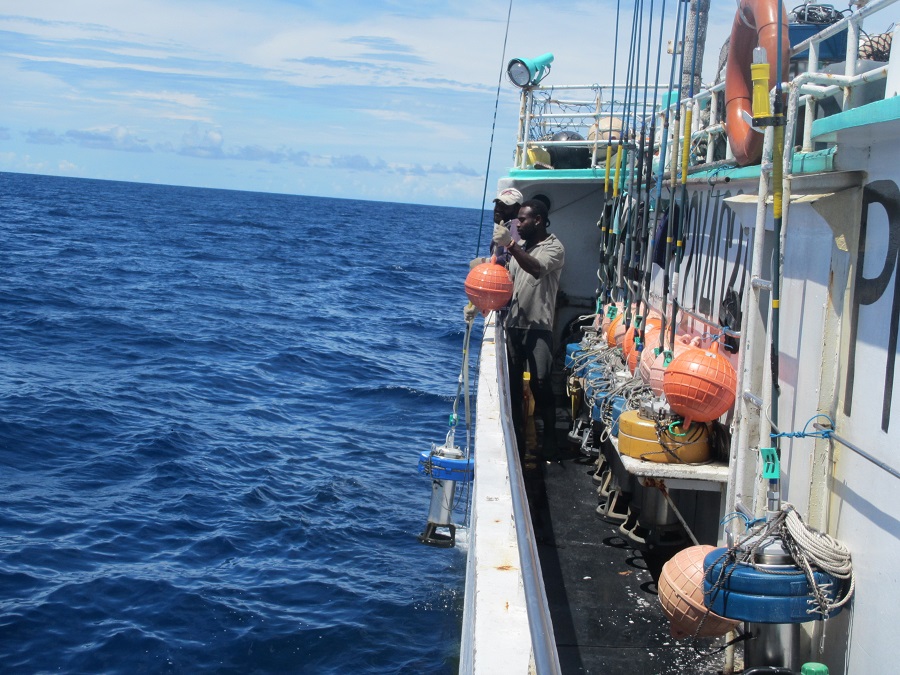

One of the commercial fishing boats we worked with in Papua New Guinea. Credit: National Fisheries Authority, Port Moresby.

The team found that two of the scalloped hammerhead litters had significant paternal skew, meaning that different fathers contributed unevenly to the number of offspring. The cause might be the order in which males mated with the female. But females of some polyandrous sharks, including scalloped hammerheads, are able to store sperm for months or even years after mating, releasing bundles of sperm from their oviducal glands. This suggests that female sharks are making choices about the use of sperm from different males. Another possible cause is sperm competition, meaning females mate with different males in order to let the sperm fight it out, hopefully resulting in fitter offspring.

“Mating systems in sharks are complex as well as fascinating,” says Madi. “They can be location-specific as well us unique to a particular species. We’re combining our observations of grey reef sharks and scalloped hammerheads with information on size and sex of sharks caught by PNG fisheries to find out if and where populations of these species are at risk of declining.”

The sharks in this study were sampled as part of an Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research project led by the National Fisheries Authority of PNG and ourselves to assess shark and ray catches in PNG’s commercial and artisanal fisheries. Madi is currently completing her PhD in the joint CSIRO and UTAS Quantitative Marine Science Program.

Find out more about our work at the Australian National Fish Collection in Hobart.