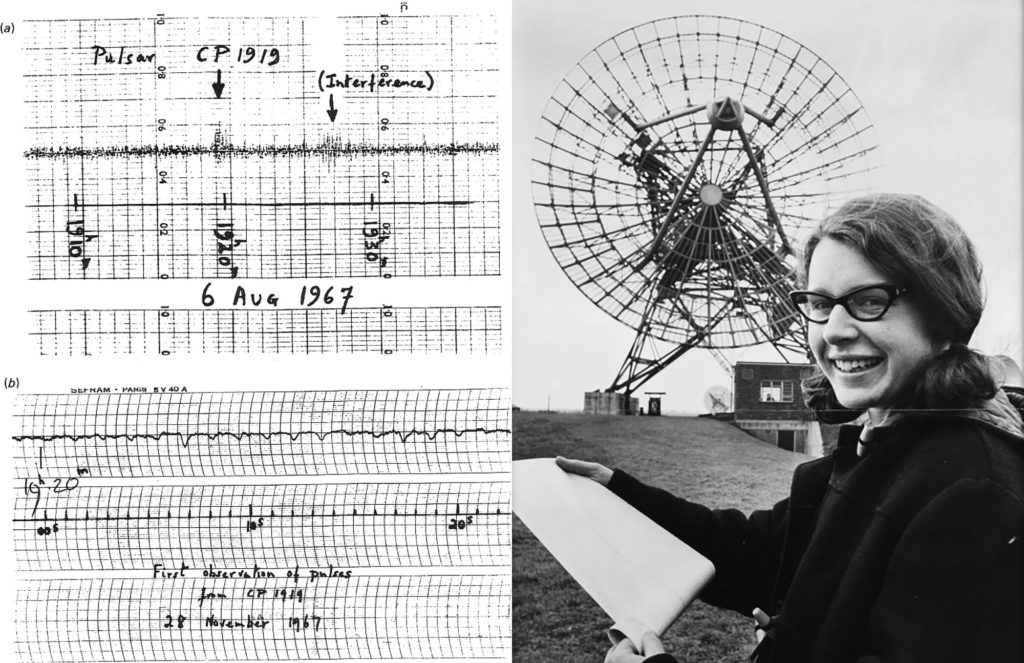

Dame Jocelyn with the record of her discovery

In 1967, as a 24-year-old PhD student at Cambridge University, Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell made one of the most significant scientific discoveries of the 20th Century when she identified and precisely analysed the first pulsar.

Dame Jocelyn recently visited Australia, and while she was in Parkes to deliver the John Bolton lecture at the local Astrofest event, she had the chance to pop in to see our Parkes radio telescope, which you probably know as ‘The Dish’. This was the first time Dame Jocelyn had visited The Dish, which has detected more than half of the more than 2500 pulsars found since her original discovery, and when the opportunity presented itself she just ‘couldn’t resist.’ And while she was here we had the chance to catch up with her to hear her thoughts on the breakneck speed of modern science, as well as the adversity women face when pursuing a career in science.

Puzzling pulsars

A pulsar is a small star left behind after a normal star has died in a fiery explosion, which spins up to hundreds of times per second and sends out beams of radio waves. We now know those radio waves can be detected as a ‘pulse’ when the beam is pointed in the direction of our telescopes.

Dame Jocelyn discovered pulsars by spotting a tiny bit of ‘scruff’ in the 30 metres of chart recordings made by the telescope each day.

“It was troubling me because it didn’t fit into any previously known category, so I was a bit puzzled by what it actually was. I started calling it ‘LGM’, which stood for Little Green Men, although I didn’t seriously believe it was little green men,” Dame Jocelyn said.

It wasn’t until she found the second pulsar that she was able to relax a little and know that the first detection wasn’t an anomaly.

“It wasn’t till that point I was able to stop and think aaah…this is a new branch of astronomy we’re opening up.”

Celebrating her 75th birthday at The Dish with a surprise cake

A trailblazing pioneer

Dame Jocelyn’s ambition when starting out was to develop a career in radio astronomy.

“I’d already felt like a bit of a pioneering woman during my time as an undergraduate, when I was the only women in a class of fifty people doing their honours physics degree,” she said.

And even though she’d been credited with such an important scientific discovery, she would go on to face adversity many times during her career. Perhaps the most high profile example is when the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded to her thesis supervisor and another astronomer in 1974 for the work discovering pulsars.

Reflecting on the incident now, Dame Jocelyn thinks “…it was far more important that there was a Nobel Prize in astrophysics, rather than what it was for, or who it went to, because it created a precedent and opened the door, because until then astrophysics hadn’t been recognised at all.”

“There were certainly discouragements, and you sometimes had to find workarounds, but it got even harder when I married and had a child, because mothers weren’t meant to work, so I ended up working part-time for about eighteen years,” Dame Jocelyn said.

“I knew that I needed to work… I was quite lucky that directors were prepared to give me part-time jobs, they weren’t very wonderful jobs, but they were intellectually engaging and enjoyable, and allowed me to work part-time, so that kept me sane and kept me in touch with the field.”

“The world is getting much better at recognising women, but there’s still not parity. There’s still more room for women, and as it becomes more normal for women to do scientific things more women will come through and play a role, which will be great,” Dame Jocelyn said.

Inspiring the next generation

Shivani Bhandari is one of our postdoctoral astronomers who had the opportunity to hear Dame Jocelyn speak while she was in Australia.

“It was an absolute honour to chair Dame Jocelyn’s colloquium and see her speak enthusiastically about her 50 year old discovery.” Shivani said.

“Her struggle to pursue research in a male dominated area of study, driven by pure passion for astrophysics, is truly inspiring for female scientists, including myself.”

Our Postoctoral astronomer Shivani Bhandari with Dame Jocelyn

Science at breakneck speed

Dame Jocelyn also had time to reflect on the breakneck speed of modern research.

“It’s fantastic seeing the technological change being applied to astronomy. The equipment on the Parkes telescope and others around the world is forever improving, and the pace of discovery just gets faster and faster as the equipment gets better. It leaves you a bit breathless, but it’s very exciting,” she said.

“It’s been magnificent to see so many developments in the field since the original discovery of pulsars fifty years ago. It’s since become a major field of astronomical research, especially here at Parkes.”

“It’s a very exciting time to be around, it’s fascinating!”

27th July 2018 at 5:07 pm

What a remarkable story and a ground-breaking scientist! Thank you!

27th July 2018 at 5:04 pm

Thank you Dame Jocelyn – you are an inspiration!

27th July 2018 at 3:43 pm

Nice to see a picture of Jocelyn and staff at Parkes after I first met her in Cambridge. Her chart records were in the drawer at Lord’s Bridge. It is also lovely to see she has now been made a DAME. Well deserved.

25th July 2018 at 5:22 pm

I am a great fan of Dame Jocelyn. She gave a fabulous lecture last time she was in Adelaide.

25th July 2018 at 3:40 pm

I have heard that Jocelyn’s PhD thesis was nearly derailed by her data discovery being somewhat unexpected. Is there any truth to this anecdote and if so, how did she manage to navigate that challenge also?

26th July 2018 at 1:00 pm

Hey David,

We asked one of our scientists who was at Dame Jocelyn’s colloquium and she actually did touch on this in her talk.

“Jocelyn’s thesis was building a telescope to make a survey of radio sources that scintillated (twinkling due to the interstellar medium which could be used to find quasars). This was the telescope that Jocelyn used to make the completely unexpected discovery of pulsars.

This discovery was a major interruption to her formal thesis work as you have heard but Jocelyn still finished her initial project and this was her PhD thesis. The pulsar discovery was added as an Appendix!”

Hope that answers your question.

Cheers,

Eliza