Using sensitive radio telescopes, including our very own ‘Dish’ at Parkes, a team of international scientists have for the first time discovered a chiral molecule outside of our solar system.

An almost full moon shines brightly above our Parkes Radio Telescope.

An almost full moon shines brightly above our Parkes Radio Telescope.

Have a look at your two hands. Even though they are mirror images of each other, they don’t exactly match (try putting a left-handed glove on your right hand). Similarly, certain molecules come in seemingly identical pairs, although they cannot be superimposed onto each other. It’s a chemical property known as chirality.

Using sensitive radio telescopes, including our very own ‘Dish’ at Parkes, a team of international scientists have for the first time discovered a chiral molecule outside of our solar system.

Still listening? Good, this next bit is important.

So what and who cares?

Although laboratory experiments will tend to produce equal quantities of the left and right-handed versions of a given chiral molecule, life on earth is made up of groups of chiral molecules that share just one handedness. For example, the amino acids that make up proteins only exist in the left-handed form, while the sugars found in DNA are exclusively right-handed.

This bias towards one type of ‘handedness’, known as homochirality, is one of the deepest and longest standing unsolved mysteries in biology. Scientists believe that processes taking place in outer space, not here on Earth, hold the key to unlocking this mystery. Which is why discovering a ‘handed’ molecule outside of our solar system is such a coup.

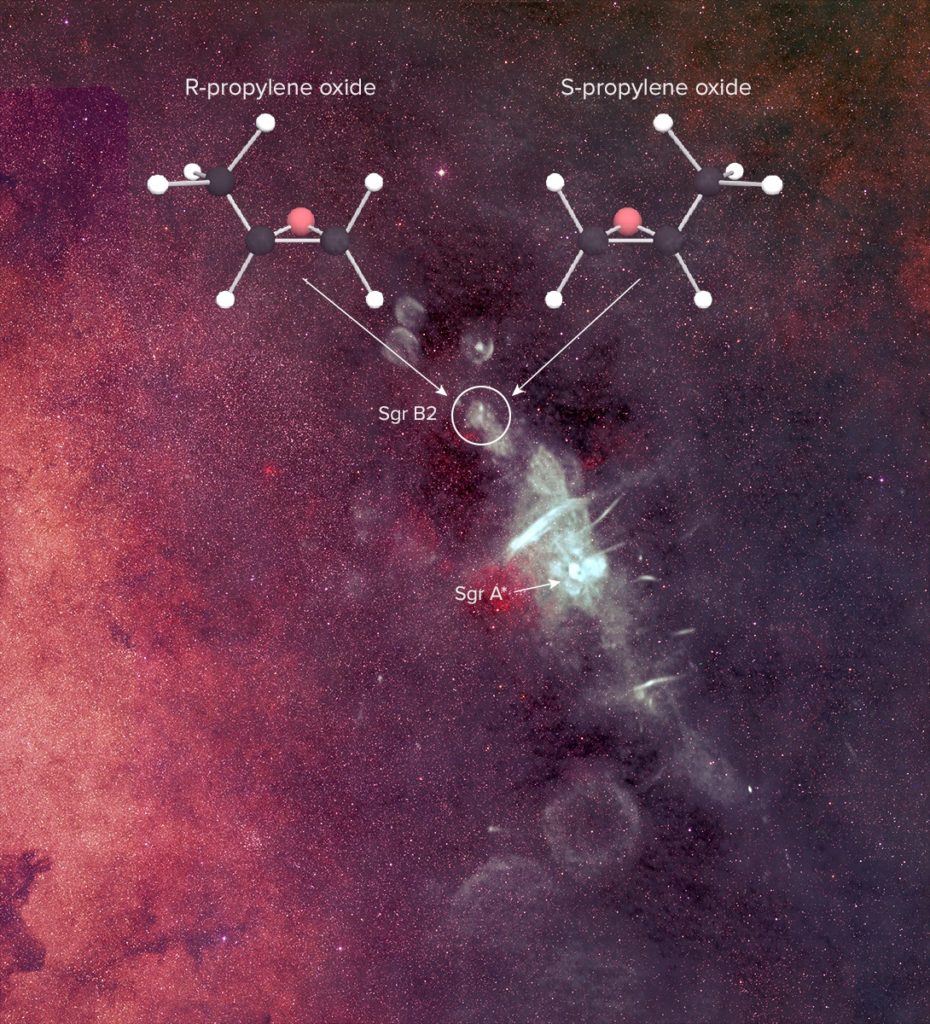

Scientists applaud the first detection of a ‘handed’ molecule, (propylene oxide) in interstellar space.

© B. Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF from data provided by N.E. Kassim, Naval Research Laboratory, Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

The first detection of a ‘handed’ molecule, (propylene oxide) in interstellar space. © B. Saxton, NRAO/AUI/NSF from data provided by N.E. Kassim, Naval Research Laboratory, Sloan Digital Sky Survey.

“The phenomenon of homochirality has exerted a powerful appeal over the scientists for many years now, as they believe solving the riddle can go a long way towards determining the origin of life on Earth,” said Dr John Reynolds Director of our Astronomy and Space Science Operations.

“We believe that the answer lies in deep space, which is why the discovery of an interstellar chiral molecule is so exciting.”

Scientists from the US National Radio Astronomy Observatory and the California Institute of Technology made the discovery by aiming two radio telescopes- the Dish at Parkes and the Green Bank Telescope in West Virginia- near the centre of our Milky Way galaxy at an interstellar cloud, Sagittarius B2, a cool 26,000 light years away (basically next door in cosmic terms). The radio waves they detected bore the fingerprints of a chiral molecule, propylene oxide, which is a common compound used in making plastic, and now the most complex molecule yet found in space

They found it – hooray! We can all pack up and go home, right? Not quite.

Now, the fun is just beginning. With a task somewhat mimicking the role of political pollsters, the next job for the scientists is to figure out if the molecules they’ve detected are mostly lefties, or righties.

14th September 2016 at 6:10 am

“Dish at Parkes serves up the answer to one of life’s greatest mysteries – maybe sometime in the future, if you’re lucky.” That’s what you meant the title to be, I’m sure. Anything else would be dishonest.

19th June 2016 at 11:01 pm

How on Earth can radio telescopes detect the structure of molecules 28,000 lightyears away?! Is it simply the frequency of the waves being emitted from the cloud?

13th September 2016 at 8:55 pm

Polarisation maybe?

14th September 2016 at 7:42 am

The molecules’ structure gives rise to emission and absorption spectra that show up as spikes in the frequency distribution. I suspect the chirality will show up in the polarisation of the light.