Tim Galvin has a big job ahead of him sifting through the masses of data generated by our world-leading ASKAP telescope

One of our Australian Square Kilometre Array Pathfinder (ASKAP) teams is preparing to produce a catalogue of 70 million galaxies. That’s a pretty solid number – it’s actually more data than has ever been detected by all radio telescopes across the entire history of radio astronomy. If you want to split hairs, it’s about 25 times the number of galaxies ever detected.

ASKAP is actually a precursor to the SKA which is a big international project to build the world’s largest radio telescope. Construction is due to start in the 2020s in Australia and South Africa. And that will mean even more data.

What to do with all that data?

So how to sift through the millions of galaxies buried within terabytes and terabytes of data? There’s a big project fittingly called The Evolutionary Map of the Universe (also known as EMU – cute!) and they have this challenge ahead of them. All that data can’t be waded through by humans alone and that’s where Tim Galvin from our Astronomy and Space Science team comes in.

Tim’s research group, which also involves the Western Sydney University and other institutions, is working to solve that data deluge with machine learning: training an algorithm to sift the supernovas from the Moon dust.

“We’ve never been so deep across such a large surface of the sky. We’re going to have way too much data,” Tim said.

Tim’s role is trying to see how machine learning can help solve particular problems. He’s working on an algorithm called ‘self-organising maps’ which will help organise different types of radio sources they’re seeing in the data surveys.

“We only want to have to worry about the cool interesting stuff. But we’re still figuring out what the ‘important’ data will look like.

“We’re at a special time where technology can do very cool things – that even ten years ago you would have said ‘no way’ to.

“For example, the idea that you could get affordable disks to store 30 or 40 terabytes of data – or CPUs capable of churning through that data.

“It’s a really cool time to be at CSIRO with big data instruments, because we’re getting to the point where we can make big strides in problems that we used to think were just too big to solve,” he said.

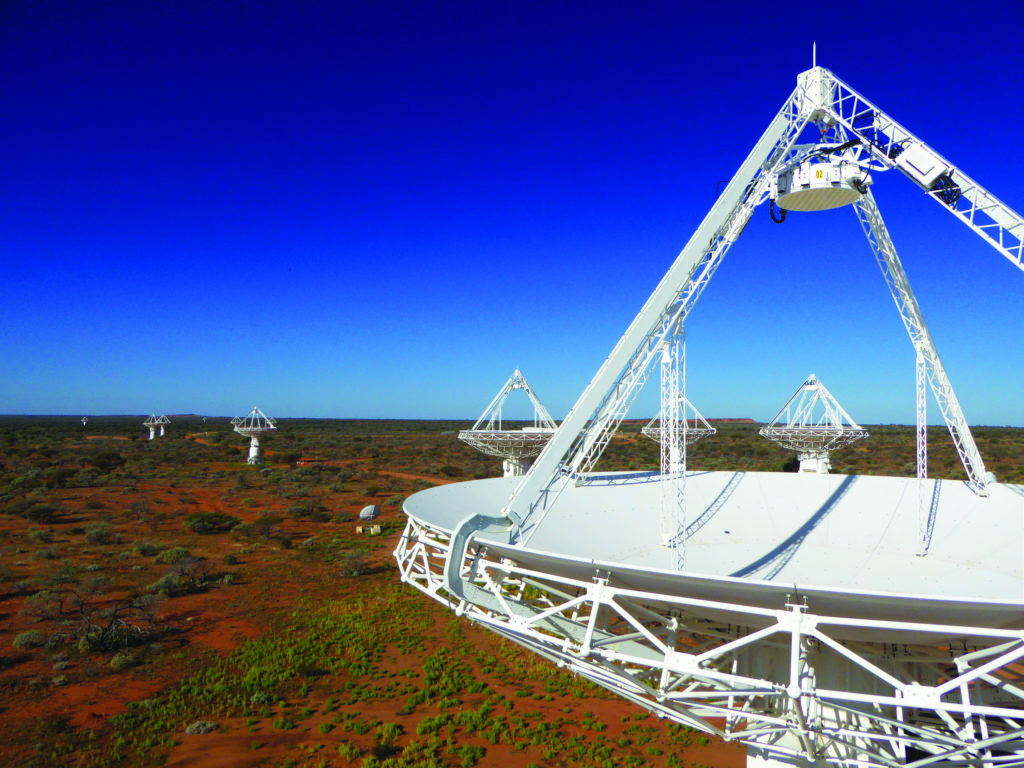

The Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP) telescope in Western Australia

Fields of vision

ASKAP is made of 36 identical 12-metre wide dish antennas that all work together as one telescope. The antennas have unique CSIRO-designed phased array feed receivers – each one creates 36 individual beams on the sky – traditional receivers have one beam. These special receivers effectively give astronomers a wide-angle lens on the Universe with a field of view of 30 square degrees – huge!

Tim’s vision is the opposite. He has a visual impairment called Choroideremia (sometimes abbreviated to CHM) which makes it like looking through a tunnel.

“It’s a visual impairment that I’ve had all my life. It’s a progressive condition – so it gets worse over time.

“My left eye is more or less gone – I can’t read or see with it, but thankfully my right eye has a really strong field of vision at the centre.

“Day to day, I can still read a computer screen easily. I have large text and colour schemes to help recognise what I’m reading, and generally the accessibility tools on most systems are exactly what I need. I’m pretty lucky.

“If I’m away from the computer, though – even doing simple things like walking around the office – that’s when I have to be quite careful.

Long-term, there’s no formal treatment for Choroideremia, and Tim will likely go completely blind. The timeframe on that is not clear but there are some promising trials from different treatments happening around the world.

CSIRO's new telescope, the Australian SKA Pathfinder (ASKAP), standing tall in Western Australia.

Don’t you hate it when you get so much data from your super-powerful telescopes that you have to build a fleet of robot brains to interpret it?!

Credit: Alex Cherney/terrastro.com

A room full of geniuses

When we ask our staff what they love most about working at CSIRO, there’s a pretty common response: the people. You can be in a room full of geniuses any day of the week. Sometimes you might be the smartest person in that room and sometimes you’re learning new and amazing things. Tim is no different.

“The more people I talk to, the more I realise how much there is that I just don’t know.

“It’s pretty common for me to walk out of a talk – and think ‘Okay, there’s five words I’m going to need to look up on Wikipedia.’

“Even within your field of expertise there’s going to be a hell of a lot of stuff you don’t fully grasp – it gives you something to work towards, and it makes me feel pretty hopeful.”