UPDATE: 25 Sept.14 – NASA’s MAVEN and ISRO’s MOM spacecraft arrived successfully in orbit and have already been returning science from Mars. The Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex, as part of NASA’s Deep Space Network provided excellent command and telemetry services for both missions. Further updates on the missions can be found on their werbsites and Twitter feeds: MAVEN @MAVEN2Mars | MOM @MarsOrbiter

LISTENING: The deep space dishes of the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex. Image: Astro0

The giant antenna dishes of the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex are set to receive the radio signals from two new spacecraft signalling their arrival in orbit above the red planet Mars. NASA’s MAVEN (Martian Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution) spacecraft and the Indian Space Research Organisation’s (ISRO) Mars Orbiter Mission (MOM) are due to arrive at Mars on Monday 22nd and Wednesday 24th September respectively. These two robotic explorers are set to turn their instruments on the Martian atmosphere to understand its composition and how it has changed over time. Getting spacecraft into orbit around Mars is never easy. Over the past 40 years, nearly two-thirds of the spacecraft that have attempted to get there have failed and few have succeeded on their first try. At the moment, NASA has the best track record and right now are operating four spacecraft either in orbit (Mars Odyssey and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter) or on the surface with rovers (Opportunity and Curiosity). The European Space Agency has its own orbiter (Mars Express) currently collecting high resolution images and ground penetrating radar data. Each of these spacecraft have their unique science assignments: mapping, looking at the surface and subsurface environments, analysing rock and soil or studying the lower layers of the Martian atmosphere.

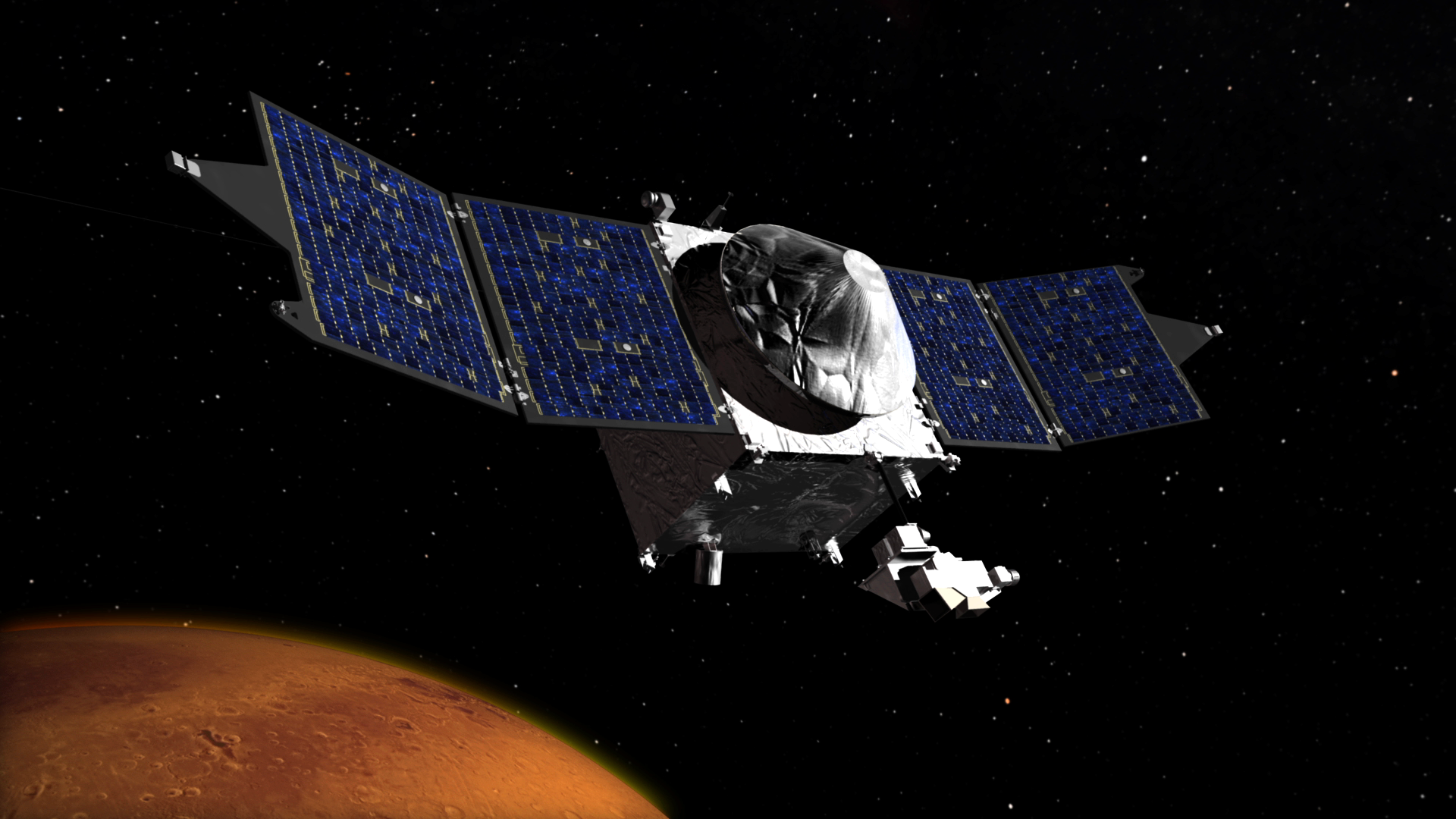

MAVEN: Mars Atmosphere and Volatile Evolution mission. Image: NASA

With MAVEN, NASA scientists want to understand changes that have happened to Mars as the sun stripped away most of its atmosphere, turning a planet once possibly habitable to microbial life into a cold and barren desert world. Previous missions to Mars have shown that the atmosphere and climate have changed over billions of years and found evidence of abundant liquid water on the surface in ancient times. Scientists want to know what happened to the water and where the planet’s thick atmosphere went. The MAVEN mission will study the nature of the red planet’s upper atmosphere, how solar activity contributes to atmospheric loss, and the role that escape of gas from the atmosphere to space has played through time. For the MOM spacecraft, ISRO’s goal is to demonstrate its launch systems, spacecraft-building and operations capabilities. As much a technology demonstrator as a science mission, MOM will showcase the technologies required for design, planning, management and operations of an interplanetary mission.

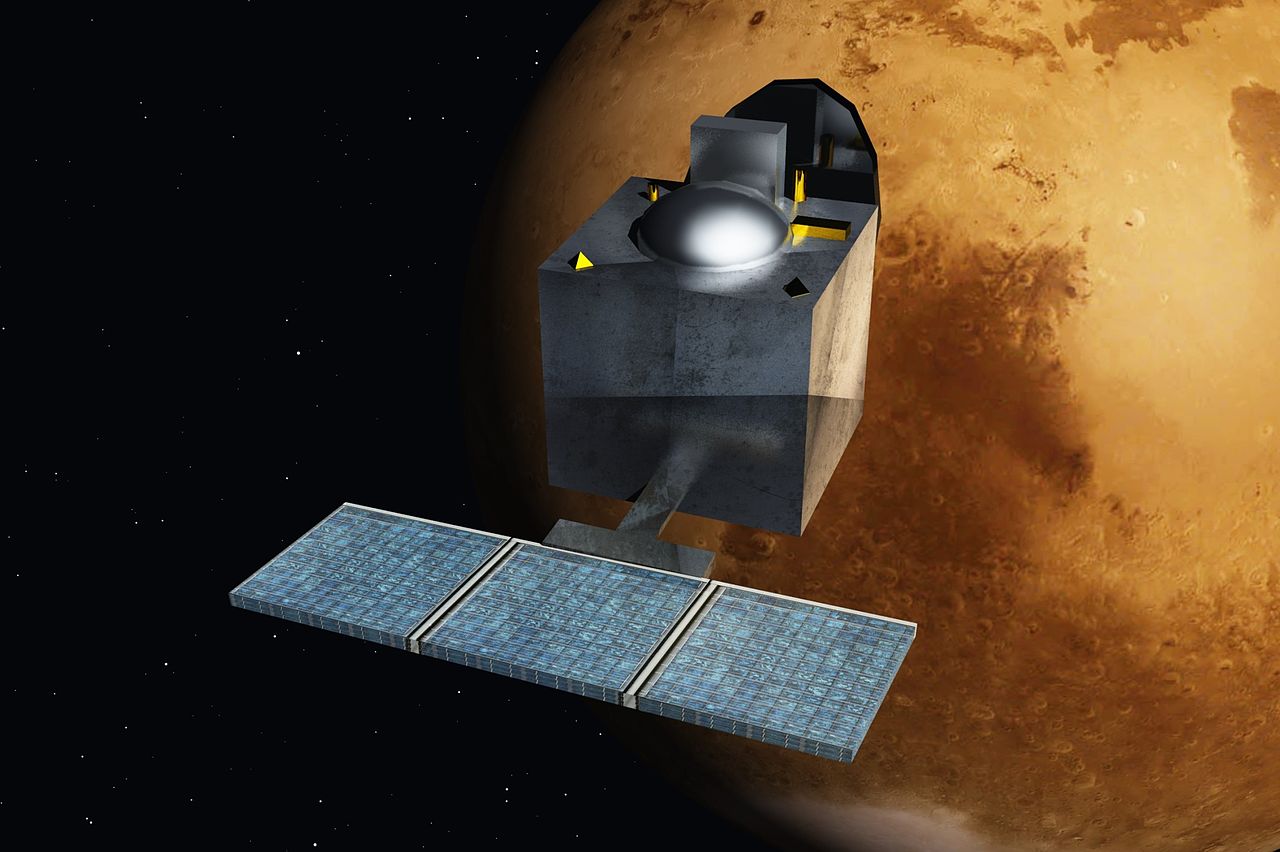

MARS NEEDS MOM: India’s first spacecraft to visit the red planet. Image: ISRO

MOM’s science goals are equally ambitious for a first time mission. Once in orbit it will explore Mars’ surface features, morphology, mineralogy and atmosphere using indigenous scientific instruments. One instrument, the Methane Sensor for Mars (MSM) will “sniff” the Martian atmosphere looking for signs of and concentrations of methane gas which can have both geological and biological origins. While studies by previous missions and Earth-based detectors have yielded ambiguous results, the detection of methane could suggest the presence of Martian microbes. For both of these missions to succeed, they first need to get into orbit around Mars. This is no easy task. One of the complexities for any mission is reliable communications to enable science teams to troubleshoot issues, relay commands and get their valuable science data back to Earth. This is the unique and high pressure role of NASA’s Deep Space Network (DSN) – three tracking stations around the world which provide two-way radio contact for the dozens of robotic spacecraft exploring the Solar System and beyond. With a third DSN station in Spain, it will be the two tracking stations in Goldstone, California and the CSIRO-managed Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex that will provide the vital link to both MAVEN and MOM during their critical Mars orbit insertion (MOI) manoeuvres. Approaching Mars at over 11,000 kilometres per hour, each spacecraft will fire their engines for approximately 30 minutes, slowing down just enough to allow Mars’ gravity to capture them into orbit.

TRACKING: Deep Space Station 43 – 70 metres wide and 22-storeys high at the Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex Image: K.McDonnell

Canberra will be the Prime station for both MOIs relaying data back to the anxious scientists waiting at the mission control centres at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California and at ISRO’s Telemetry Tracking and Command Network in Bangalore. Capturing these tiny signals and confirming that the spacecraft have successfully entered orbit will fall to the largest antenna dish in the southern hemisphere, Deep Space Station 43, which has been a workhorse for the DSN for over 40 years. It is a dish that has supported many great missions and the arrival of two new spacecraft at Mars this month just adds to its rich history. Along with her dedicated team of CSIRO engineers and technicians, and in hand with colleagues at the DSN station in the United States, MAVEN and MOM will be given the smoothest ride possible as they enter orbit above the dusty plains of Mars.

The Canberra Deep Space Communication Complex is managed on NASA’s behalf in Australia by CSIRO Astronomy and Space Science.