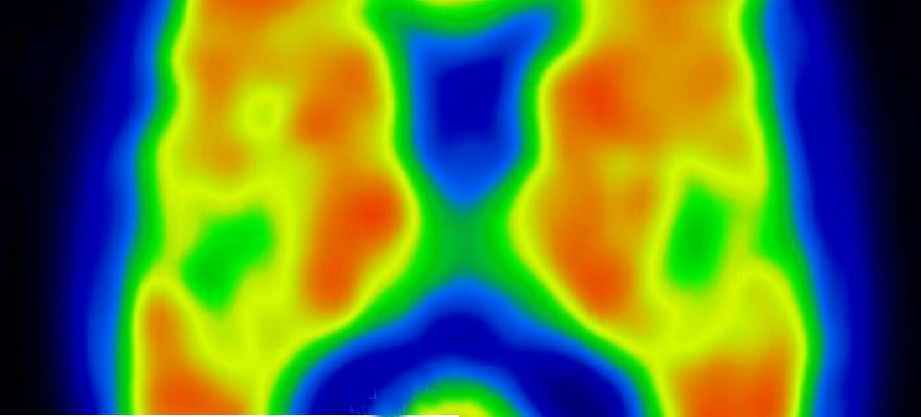

Scientists are using brain scans to help understand post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

Scientists are using brain scans to help understand post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

This Anzac Day, Australia and New Zealand commemorate 100 years since the beginning of WWI’s Gallipoli, a campaign famous for its heroism and infamous both for its terrible death toll and the horrific conditions on the battlefield.

Despite generations of war veterans developing mental health issues as a result of their service, it was not until 1980 that post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was formally recognised. Even today, PTSD remains a misunderstood, misdiagnosed condition, for which there is no widely effective treatment.

Currently diagnosis of PTSD in the military relies on paper-and-pencil tests and screening interviews by psychologists who assess servicemen and women pre-deployment, pre-extraction and post-extraction.

Now, researchers are turning to brain-imaging to improve their understanding of the condition. They’re trying to identify the physical characteristics that may help explain why some individuals subjected to trauma develop PTSD, while others exposed to identical trauma do not.

“You can be in the same armoured vehicle and only one of the four in the vehicle will subsequently develop mental health issues,” explains Miriam Dwyer, CEO of the Gallipoli Medical Research Foundation.

“When it comes to breaking your arm, we know how to fix it; or if you have blood-pressure issues, we can sort that out. But when it comes to mental health issues and the brain, we have a long way to go.”

A miltary psychologist’s interviewing set-up in an open-air chapel.

A miltary psychologist’s interviewing set-up in an open-air chapel.

Miriam is excited to see the outcomes of a major study by the Gallipoli Medical Research Foundation into the physical health and genetics of 300 Australian Vietnam veterans. Of the 300, half have PTSD, and half do not; and in a sub-study, 100 of the veterans (50 sufferers and an equal control group of non-sufferers) have undergone MRI brain imaging.

Stephen Rose from CSIRO is charged with analysing the 100 sets of images.

“We’re looking at the volume of particular parts of the brain that may predispose individuals to PTSD, believed to be the hippocampus and the amygdala, which are in the temporal lobe and some frontal lobe structures as well, particularly the anterior cingulate. These parts of the brain seem to be very vulnerable to injury, which may predispose people to PTSD, especially in the military,” he says.

“We can measure the volume of these regions of the brain very accurately and look at cohorts of Vietnam veterans who have PTSD, and compare those with cohorts of Vietnam veterans who don’t have PTSD. That may give us some insight into whether these parts of the brain are associated with PTSD, or predispose people to developing it.”

The study is also measuring the brain’s white-matter tracks using a combination of diffusion imaging and a technique called tractography to see the effect of mild traumatic injury on the brain.

These kinds of invisible injuries are prevalent in the military and can occur, for example, when a soldier is near an explosion, even if there is no observable physical injury.

“What is postulated is that having a mild head injury may increase the accumulation of toxic material in these vulnerable parts of the brain, and may increase the risk of people going on to have PTSD. There’s a lot of interest from the military in measuring these subtle brain injuries.”

Tracers developed by GE are also being used to study biochemical changes inside the brain that indicate either short- or long-term damage to brain tissue, which may be the beginning of a disease developing. These enable specialists to look for ‘hotspots’ in the brain, which previously was only possible post-mortem.

Stephen stresses that the team’s research is in its early days, but he’s excited by its potential to help.

As Miriam says, “we understand the consequences from a psychological perspective of PTSD, but not the specific causes”, which is why this research is so important.

“We know what the symptoms are when you develop PTSD, but the treatments are still not great. The standard treatment is exposure therapy, and that works well in about one-third of patients; doesn’t work at all in another third and it can actually have a negative impact for some patients if delivered incorrectly.

“There aren’t any very good drugs in development for PTSD, probably because of the complex combination of emotional, cognitive, behavioural and biological symptoms. We’re still really trying to understand how we can effectively engage and treat all sufferers—not just one-third.”

This is an edited extract from GE Reports. Read the full feature here.

27th April 2015 at 3:21 pm

Reblogged this on Darque Thoughts.