A decades-old problem in predicting Irukandji blooms has been solved by a team of our scientists, and the results could directly benefit northern Australia’s community and its tourism industry.

Last year we wrote about a new Irukandji forecasting system that Dr Lisa-ann Gershwin and her team were testing in northern Queensland.

The team were looking to prove a link between Irukandji blooms and weather conditions, based on a hindcast of previous Irukandji stings and correlating weather records, so that they could accurately predict future blooms.

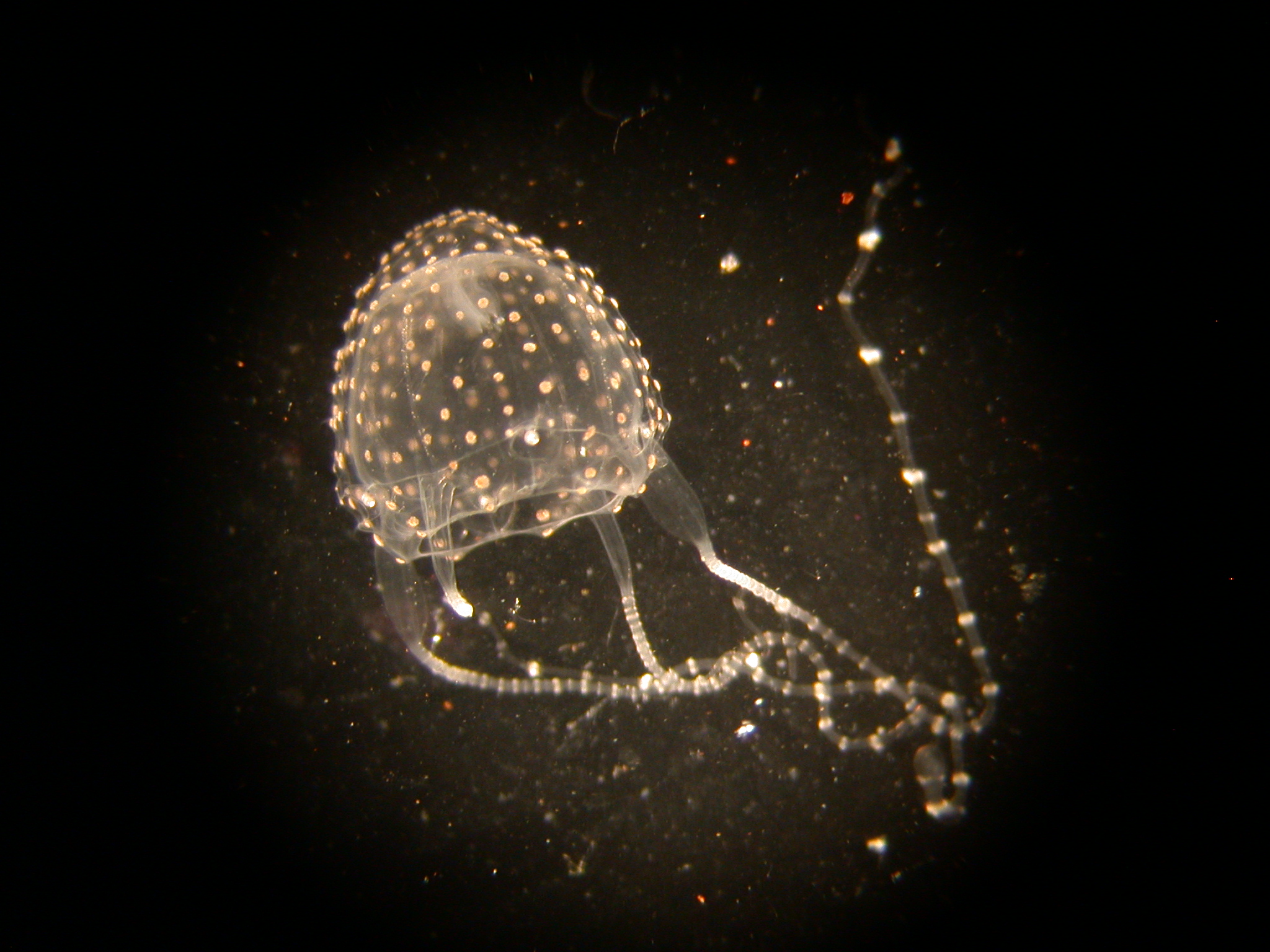

A picture of an Irukandji jellyfish.

Carukia barnesi, the so-called ‘common Irukandji’, taken in sampling nets at Palm Cove near Cairns. Credit: Dr Lisa-ann Gershwin.

In a paper published today in the Journal of the Royal Society, Lisa-ann and her team have presented their findings, which demonstrate a clear link between Irukandji blooms and trade winds – or lack thereof.

Says Lisa-ann, “We know that Irukandji blooms generally co-occur with blooms of another invertebrate, called salps. We also know that salp blooms are triggered by upwelling, which in northern Queensland is driven by subsidence of trade winds. Sure enough, when we investigated we found a clear connection between recorded Irukandji ‘sting days’ and days when there was little to no trade wind present.”

Around Palm Cove, a beach near Cairns where the tests took place, the southeast trade winds are the dominant wind most of the time. These trade winds cause a net downwelling pressure that pushes the water downward and out to sea. However, when these winds begin to ease in the summer months, an upwelling occurs. It is these upwellings that Lisa-ann and her team believe transport Irukandji to the top of the water column – and on towards shore.

A picture of an Irukandji sting.

The subtle marks of an Irukandji sting belie their deadly potency. Credit: Dr Lisa-ann Gershwin.

Finding this elusive key to Irukandji bloom prediction has been a long process.

“More than 70 years worth of work has gone into trying to accurately predict Irukandji blooms, and I myself spent 18 years attempting to establish a link,” says Lisa-ann

“It wasn’t until I came to CSIRO and collaborated with my co-authors, who are ecological and oceanographic specialists, that we made the connection.”

This early warning system could potentially allow individuals, communities, councils and governments, as well as other marine industries, to know about Irukandji blooms up to a week in advance. By being able to predict Irukandji blooms, we can reduce the direct threat to ocean-goers by closing beaches, and also reduce anxieties and uncertainties associated with areas known for Irukandji stings.

A picture of a sign showing a beach closure due to Irukandji.

A beach closure at Palm Cove due to an Irukandji bloom. Credit: Dr Lisa-ann Gershwin.

Lisa-ann says this study is just the first step. Further refinements and testing mean that we could provide greater certainty in prediction, and further reduce the rate of Irukandji stings. The system also has the potential to be rolled out at a national and international level.

“However, we must reiterate that this forecasting system is not a miracle cure for Irukandji,” says Lisa-ann. “We can never remove the threat completely.

Visit our website for more information on the Irukandji forecasting system.

For media enquiries or a copy of the Royal Society paper abstract contact Kirsten Lea, +61 2 4960 6245 or kirsten.lea@csiro.au