Don't worry, it's still better to live with hundreds of mini-beasts than that terrible housemate you had to live with during uni.

Do you take pride in a clean house? They may not be obvious, but a recent US survey has shown that each of our homes harbours a fauna of perhaps hundreds of species of insect and other terrestrial arthropods such as mites, millipedes and centipedes.

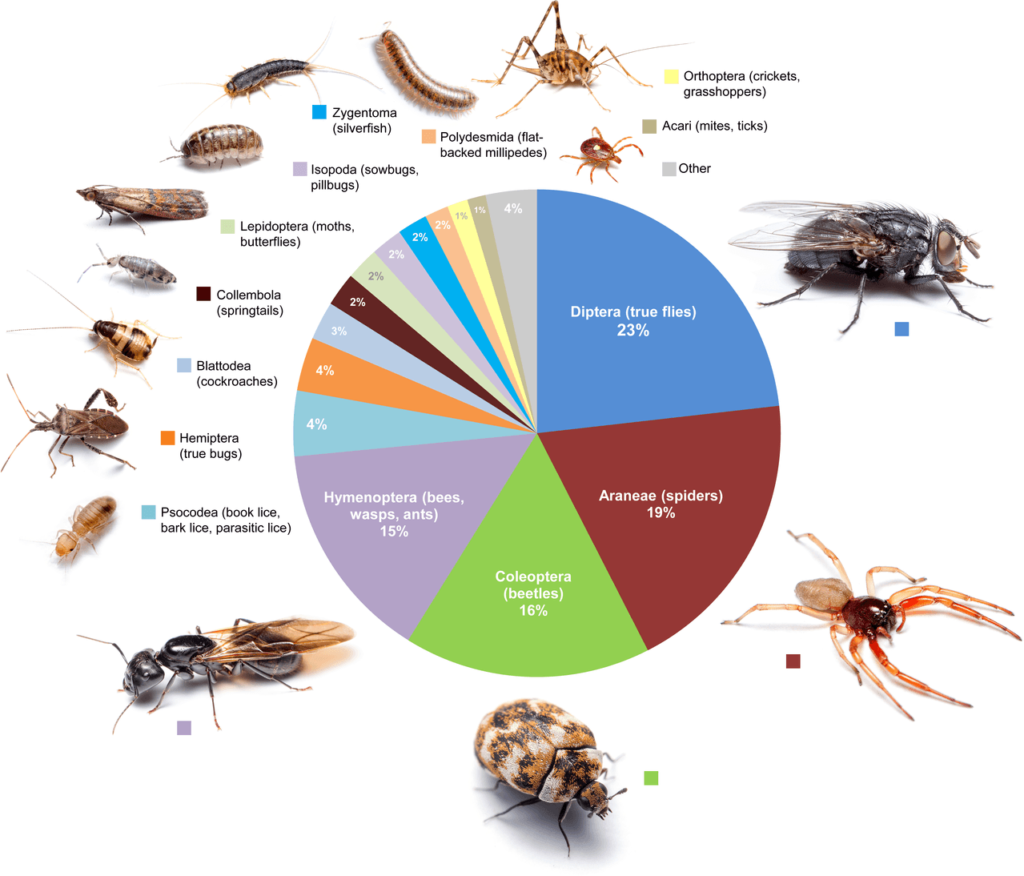

The survey, conducted in free-standing houses in Raleigh, North Carolina, sampled every arthropod, both known pests and others. Almost 75% of the diversity consisted of just four main groups, true flies (Diptera), spiders (Araneae), beetles (Coleoptera), and wasps and ants (Hymenoptera).

Most of the species are not the ones you might traditionally associate with houses, such as German cockroaches (Blattella germanica) and house flies (Musca domestica), but rather tended to be local arthropods filtered from the surrounding landscape.

More than 500 rooms were surveyed in total, and a staggering 99% of them contained arthropods. Insects were overwhelmingly common, with over 90% of kitchens, bedrooms and bathrooms harbouring them. The bigger the house, the more species it contained, and the human inhabitants were generally unaware of their uninvited guests.

How do these insects enter homes? As in Australia, most US homes have fly screens installed on windows, but many of these arthropods are small and can enter through the gaps around doors and windows, chimneys, drains, basements, attics and ceiling spaces.

Although no similar study has been done in Australia, it would probably uncover similar results. So what are all these mini-beasts doing in our homes?

Pie graph displaying different creatures found in the home.

Proportion of different arthropods found in homes: there are a lot of flies and spiders. Bertone et al, CC BY

Meet the arthropods

Arthropods have been living in our homes ever since we moved out of caves and built houses. For example, the remains of a variety of beetles that consume grains are common in Egyptian archaeological sites more than 3,000 years old.

Animal domestication and food storage brought many different opportunities for arthropods to make a living where we live. Some, such as bed bugs, may have followed us out of the caves.

Most studies have focused on known pests, with particular emphasis on medically and economically important species such as mosquitoes, termites, fleas and dust mites.

The US study was the first to uncover the multitude of other non-pest species in our homes. Their true interactions with humans remain largely unknown. None is known to cause us any direct harm.

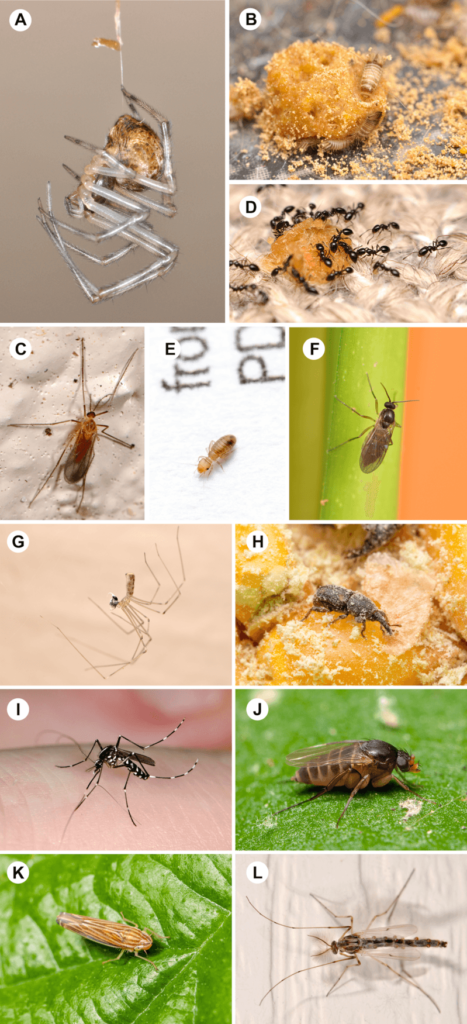

Table showing the most common mini beasts.

The most common mini-beasts in homes: (A) cobweb spiders (B) carpet beetles © gall midges (D) ants (E) book lice (F) dark-winged fungus gnats (G) cellar spiders (H) weevils (I) mosquitoes (J) scuttle flies (K) leafhoppers (L) non-biting midges Bertone et al, CC BY

Common groups found in almost all houses included cobweb spiders (Theridiidae), carpet beetles (Dermestidae), gall midges (Cecidomyiidae), ants, book lice (Liposcelididae), and fungus gnats (Sciaridae). Dust mites and American cockroaches were found in 75% of the houses sampled. Flies were found in over 80% of homes, but the commonest ones (non-biting midges, Chironomidae; and gall midges, Cecidomyiidae) are harmless and form part of the aerial plankton outside homes.

Interestingly, none of the homes surveyed had any bed bugs. This suggests these insects may thrive best in motels, hotels and hostels rather than in permanent residences.

Book lice have a broad diet, including grain, fungi, paper products and organic waste, and have a long history of living in close association with birds and mammals and their nests. They can survive for long periods without food and females can reproduce without sex (parthenogenesis). Both these attributes contribute to their success.

A whole ecosystem in your living room

The insects found have a range of different relationships with people, from species that have a very strong association (for example, carpet beetles, cobweb spiders), to others that seek shelter and resources only occasionally (ants, hunting spiders), to others that blunder into our homes and are trapped to their detriment (plant-feeding bugs and gall midges).

Many of the insects found were plant feeders. The were probably attracted into the home by lights at night, or introduced via cut flowers, and cannot complete their life cycle in the home.

Some, such as the fungus gnats (Sciaridae), may be able to complete their life cycle in the soil associated with indoor plants. Some predators, such as spiders, are able to feed on other arthropods in the home, and others are tiny parasitic wasps, which may be able to complete their life cycle on other arthropods in the home.

In these cases our homes may contain very simple, but self-sustaining, ecosystems.

Many of the insects found in the US homes are a sample of the local arthropod fauna that are not known to cause us any direct harm. All the pest groups in the US homes are also present in Australia and elsewhere.

These results suggests that if a similar survey was conducted in an Australian city, a minority of the insects would be the cosmopolitan pests found in human houses all over the world, whereas the majority would be a sample of the local Australian arthropod fauna.

Should we be worried? Probably not – other recent research has shown how diverse the arthropod fauna is in urban areas as well. If your home harbours a healthy arthropod fauna, it is safe for you as well. Whether we like it or not, we have evolved with a zoo of arthropod mini-beasts in our dwellings and suburbs for millions of years.

This article is part of a series profiling our “hidden housemates”. Are you a researcher with an idea for a “hidden housemates” story? Get in touch.

![]()

David Yeates, Director of the Australian National Insect Collection, CSIRO

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.

10th March 2016 at 12:27 am

if anyone can help…I have this Something floating around in my apt, if you go into the bathroom an turn the fan on you can feel it crawling in yo nose eas scalp, and after a bit it feels like you have sand on you face feel like these things igch through your cloths any thoughts? most are tiny tiny like lint and stick to you and some are black specs