A clever statistical analysis could lead to quicker healing bones. Image credit: Flickr.com/taedc

By Andrea Wild

Statistics help us with many things. Using stats we can count how many whales there are in the sea, protect the Great Barrier Reef from agricultural run-off, and even decide whether playing lotto is a good investment or not. In fact, stats could even help us better grow our own bones back.

Thanks to a mishap on the soccer field, a car accident or a disease like osteoporosis, many of us will need to grow new bone at some stage of our lives. Luckily, our stem cells are pretty good at patrolling our bodies and fixing any damage. But when bones need help to heal, surgical grafts (of either bone itself or a biomaterial) can encourage new bone to grow in the right place. These biomaterials are used in medicine to repair or replace diseased or damaged parts of the body.

The UK’s Imperial College London (ICL) has been developing a biomaterial known as strontium-modified bioactive glass for use as a bone graft. The bioactive glass dissolves slowly and releases the strontium, which coaxes mesenchymal stem cells to turn into bone cells, healing the damaged bone.

But how does it work? What’s happening inside the cell? Many researchers have wondered.

Thanks to what are known as gene expression microarrays, it’s possible to screen the body cells’ response to a treatment at the genetic level. But this process creates masses of data, which can be a mystery in themselves. The answers are in there, but where?

Enter our computational modellers, led by Dave Winkler, and their new statistical technique for analysing gene data: sparse feature selection. They collaborated with the ICL’s Helene Autefage and Molly Stevens, who head up one of the world’s leading biomaterials groups, to solve the strontium bioactive glass mystery.

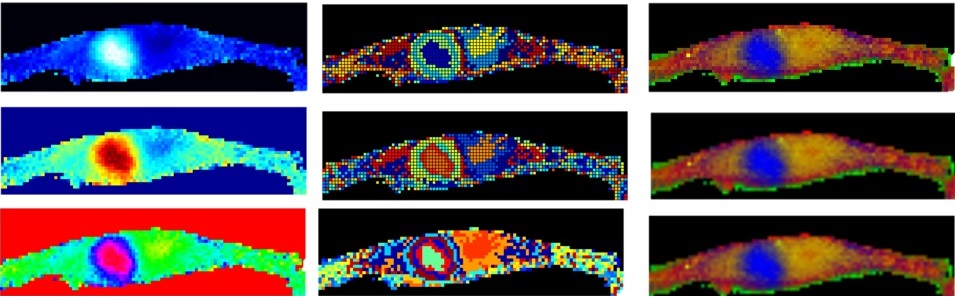

A close up of strontium-treated cells. Understanding why strontium helps bones grow could aid new drug development.

Here’s how it works, in four easy steps (not that we suggest trying this at home):

- Take human mesenchymal stem cells from three patients and treat them with strontium bioactive glass extracts.

- Run a microarray experiment to find out which genes have been effected by strontium in these cells.

- Put the data into a hat.

- Wave your sparse feature selection wand, and pull out eleven genes that matter most in stimulating bone growth from the 1000 or so genes that were influenced by strontium.

Sounds simple, right? We should note that we glossed over some very important researchers and their work, which you can learn more about here.

But the next step is the really exciting bit: drug discovery. Understanding why strontium helps new bones grow opens the way for drug development.

Statistical analysis has taught us that the biological pathways involved are those that make fatty acids and sterols inside our cells. If we can use this knowledge now to develop more targeted drugs, it’s possible that some surgical bone grafts won’t be necessary in the future. There may be a less invasive way of encouraging bone to regenerate and that would be fantastic news for an ageing population facing degenerative diseases like osteoporosis.

Taking similar steps to provide in-depth knowledge of the effects of specific biomaterials on cell behaviour could lead to new treatments for many different diseases that are more effective, easier to administer, less toxic, and cause fewer side effects.

And it’s all thanks to a little statistics.

This research was published today in the journal PNAS. Read about other new health technologies we’re developing.

For media inquiries, contact Andrea.Wild@csiro.au or +61 415 199 434

25th March 2015 at 11:06 am

I’m all for stats, however [and no offense], I don’t think stats allows us to “count” how many whales there are in the sea. Perhaps Calculate? estimate? divine? guess? figure?

Thank you for the interesting article. I presume the strontium glass is introduced surgically, are the 1000 or so genes that are affected, affected randomly or according to gene type/structure? Is the same process analogous to growing unwanted bone [spurs/arthritis etc]? Are there photoluminescent products?

26th March 2015 at 11:59 am

Hi Lu

Thanks for your question. We put it to the scientists who worked on the project:

“The effects on genes is not random. Genes are not isolated and so the expression of some genes influences the expression of others, in a kind of connected ‘social network’ way. This makes it very hard to work out which are the really important genes. The value of our research is that we’ve come up with a way of finding them.”

Cheers

Nick

24th March 2015 at 4:13 pm

Hi Alexander,

Regarding the other part of your question, there are four naturally occurring (non-radioactive) isotopes of strontium. 88Sr is the most abundant (83%), followed by 86Sr (10%), 87Sr (7%) and 84Sr (<1%). None of the other twenty or so radioactive isotopes of strontium are naturally occurring, they are generated in nuclear reactors, or by nuclear explosions. See wikipedia http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Isotopes_of_strontium

24th March 2015 at 12:54 pm

I hope this isn’t Sr 9O which was implicated in contaminating Ca in milk during

atmospheric atomic bomb testing in the fifties and sixties.

Strontium 9O has a half life of 28 years so it should have still significant levels

of radiation biohazard.

I don’t know what percentage of native Strontium is Sr9O a radioactive isotope.

24th March 2015 at 2:43 pm

Hi Alexander,

Thanks for your question. No – the strontium in the bioglass treatment is naturally occurring, and as such, not radioactive.

Nick