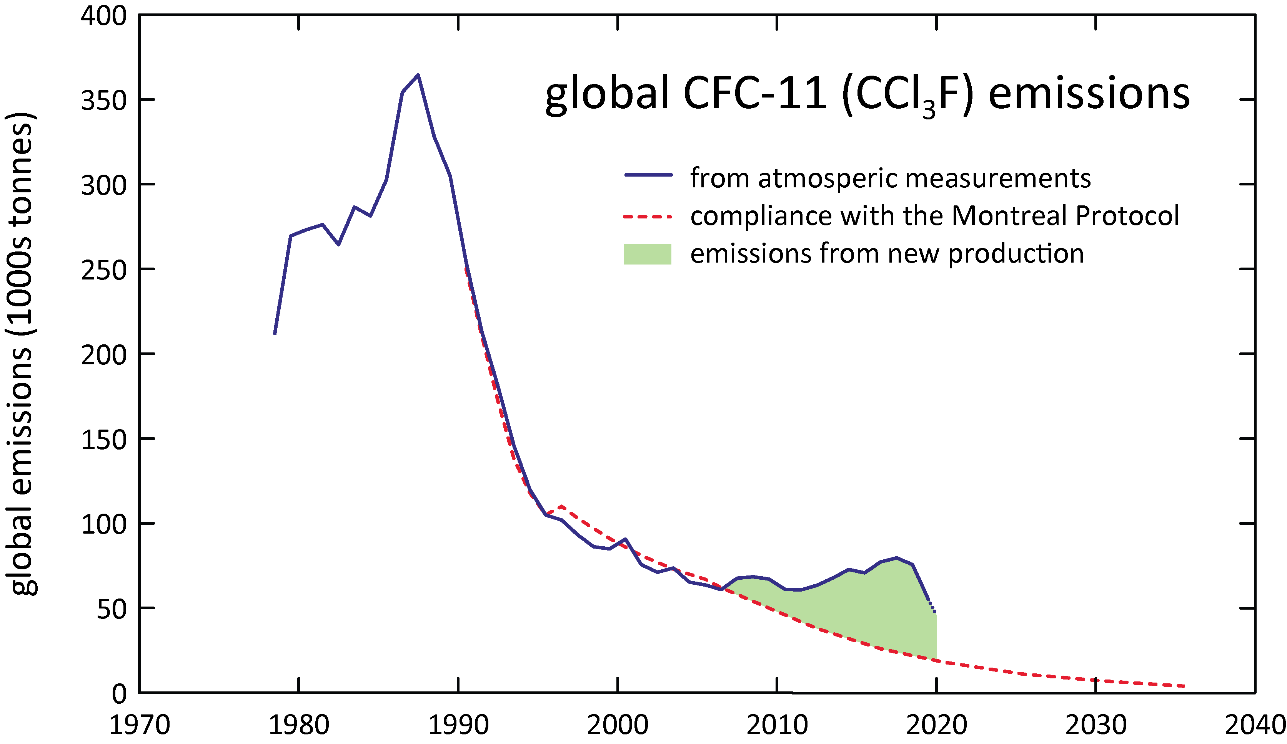

New research shows that global CFC-11 emissions have declined, returning to pre-2013 levels.

Good news! New research published in Nature shows that global emissions of chlorofluorocarbon-11 (CFC-11), an ozone-depleting substance, have begun to decline again.

Atmospheric monitoring shows they decreased by about 25 to 30 per cent from 2018 to 2019. As a result, current global CFC-11 emissions now appear to have returned to pre-2013 levels. Furthermore, monitoring showed a decrease in emissions from East China – the source of increased global CFC-11 emissions.

This follows an unexpected and concerning increase in emissions between 2014 and 2017.

Tracking the rise and fall of these damaging ozone-depleting and greenhouse gases is possible thanks to the global network of atmospheric monitoring stations. This includes our Australian Cape Grim Baseline Air Pollution Monitoring Station.

Emissions begin to rise

In 2013, it came as a surprise to the scientists monitoring global CFC-11 emissions that levels were rising. Until then, emissions were falling since the late-1980s thanks to the (previously highly successful!) Montreal Protocol. It outlawed the production and use of CFCs in developed countries and introduced a global ban in 2010. The 2013 finding was gravely concerning as CFC-11 is a powerful ozone-depleting chemical that plays a major role in the appearance each austral spring of the ozone hole over Antarctica.

To track down the source, researchers at the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration did some impressive detective work. They discovered that the rise in emissions was likely due to new, illegal production of CFCs in East Asia. This finding is impressive as it’s largely based on data collected at an atmospheric monitoring station over 8000 km away in Mauna Loa, Hawaii.

An international research team, which included scientists from our very own Climate Science Centre, determined a more exact epicentre of emissions in 2019. The team showed that the new CFC-11 emissions were coming from eastern China (and even more precisely the provinces of Shandong and Hebei). They used measurements compiled by the Advanced Global Atmospheric Gases Experiment (AGAGE), which includes those from Cape Grim.

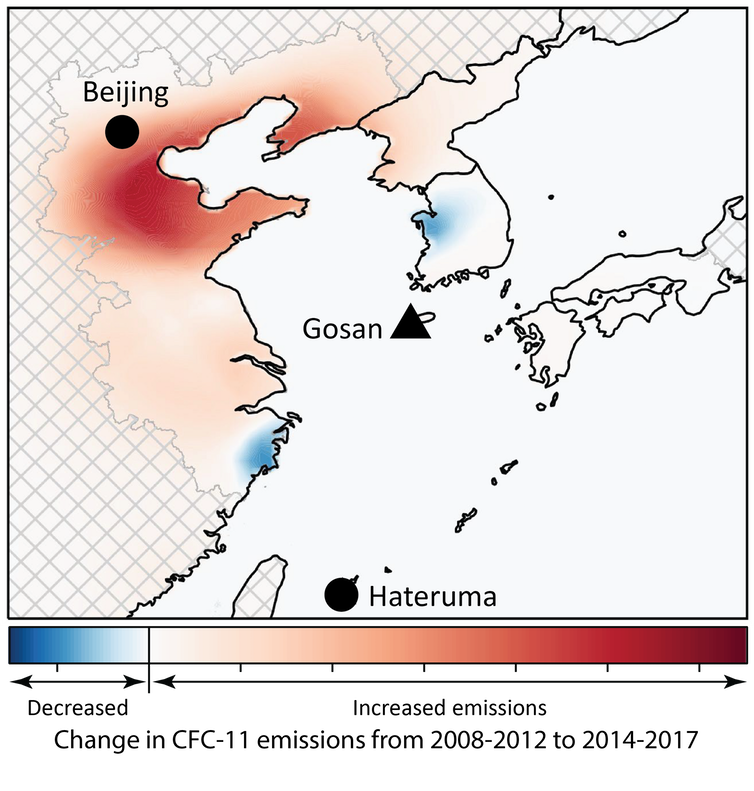

Map showing the region where the increased CFC-11 emissions came from. It’s based on atmospheric measurements and modelling report in the 2019 study. Image: University of Bristol/CSIRO

A global effort to minimise emissions

This finding assisted Chinese authorities to identify and close illegal production facilities. However, no one observation station could do this alone. The full network of observation stations was integral to finding the source of illegal emissions.

Gosan, South Korea and Hateruma, Japan were the stations closest to the epicentre of emissions. Their data showed an increase in the frequency and size of pollution episodes (times of high pollutant levels lasting hours to days) when air travelled from China. On the other hand, data from stations elsewhere around the world showed increases in the background levels of CFC-11 but decreases in the pollution episodes. Consequently, this helped pinpoint where the emissions came from.

Dr Paul Fraser, a CSIRO Honorary Fellow and the ‘Air Man of Cape Grim’, was surprised to see the rapid turn-around in emissions in the newly released research.

“Even more remarkable is that the decline over the past two years was as large as, or perhaps bigger than, the original rise,” Paul said.

“This whole story is really encouraging. It shows that the observational systems we have in place to ensure we get early warnings of violations of the Montreal Protocol are working. It demonstrates the importance of atmospheric monitoring stations in supporting the recovery of the stratospheric ozone layer.”

Global CFC-11 emissions based on atmospheric measurements from the AGAGE global network, compared to expected emissions under the Montreal Protocol. Image: CSIRO/AGAGE

More challenges to come

The global atmospheric monitoring network may have passed this test with flying colours. However, there are likely challenges ahead.

Two families of chemicals – hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) – will be phased out over the coming years. These chemicals have replaced CFCs and do less damage to the ozone layer. But, like CFCs, they’re very potent greenhouse gases that contribute to climate change.

The Montreal Protocol must continue to ensure the international community abides by their agreements to phase out HFCs and HCFCs. This also includes the monitoring network that supports it.

Expanding the global coverage of the atmospheric monitoring network would help meet this challenge. This would mean that likely emissions from India, Russia, Africa and South America could be added to those from Europe, North America, China and Australia. As a result, this would reduce the current uncertainties surrounding the magnitude and location of synthetic greenhouse gas emissions sources.

13th February 2021 at 11:33 am

there was no mention of when CFC’s were first banned.

When was it? I remember the time well but it was a good decade or two ago.

Maybe an article on it, reminding us all how long it takes for changes to be felt by the environment?