Animal super powers in action – Maya the Koala detection dog. Photo: Nic Gill

Nicole Gill is a self-described ‘story-hoarder’. An environmental management specialist by trade, she found herself squirrelling away notes and clippings that piqued her interest.

“I just stockpiled random news clips – miniature hippos found roaming the Australian outback, dogs that could predict epileptic seizures, bees trained to fly through wind tunnels. I was away for work at a particularly creepy, 80s motel when the idea hit me – I suddenly realised that among the stories I’d collected ran a theme of animal exceptionalism,” she said.

Nicole’s fascination with animals knows no bounds

And, so her idea for a children’s book was born. Released in 2017, Animal Eco-Warriors tells the story of a group of animals who use their special talents to help solve environmental problems – biosecurity beagles and guardian dogs, cyborg bees with backpacks, and landmine detecting hero-rats. While Gill had written about science for young readers in magazine articles (including CSIRO’s Double Helix), Animal Eco-Warriors marked her first foray in to book publishing.

Dogs can smell fingerprints and bees that make fake spiders out of mud

“I thought children would be amazed by what are effectively ‘animal super-powers’. Whether it be dogs’ super-sensitive noses – they can smell fingerprints! – or stingless bees that have evolved to sculpt mud spiders to scare away honey thieves. Most people are impressed by what over-achievers animals are in their respective fields,” she said

Overachieving animals also inspired Melbourne Zookeeper Rohan Cleave’s first children’s book, Phasmid: Saving the Lord Howe Island Stick Insect.

Each night, Cleave’s two children would curl up and listen to their dad reading bedtime stories. It soon occurred to Cleave that he knew a true story as extraordinary as fiction.

Rohan Cleave with an adorable bandicoot. Photo: Rick Hammond Zoos Victoria

For nearly 80 years, it was believed the Phasmid had vanished forever – pushed to extinction by hungry black rats. But miraculously the Phasmid had clung on, surviving on a sea stack called Ball’s Pyramid, 23 kilometres off the coast of Lord Howe Island. Cleave, who worked with Phasmids, began writing their story.

“I would read it aloud and gauge my children’s reactions,” he said. “I’d go back to the drawing board if something didn’t flow or they didn’t understand. This went on for years as it was a private story for my children.”

But Cleave began to see potential in his private story.

“My ambition was to bring different fields together: conservation work, children’s publishing, science and art.”

Cleave teamed up with illustrator Coral Tulloch and Phasmid was published in 2015. This year, Cleave published his second book with Tulloch, Bouncing Back: An Eastern Barred Bandicoot Story.

“Science is all around us and the more people we can inspire the better for our future,” said Cleave.

Communicating science

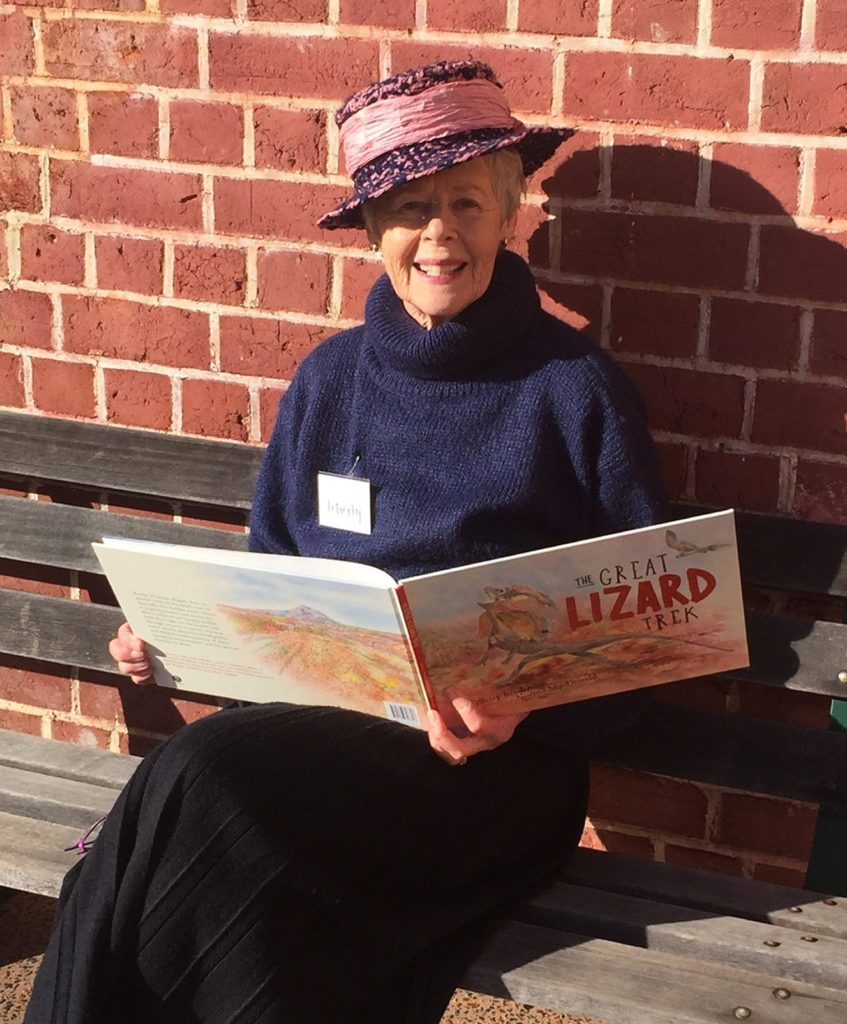

Felicity Bradshaw with her book The Great Lizard Trek

Environmental biologist Felicity Bradshaw has published books for children but doesn’t consider herself a children’s author.

“I love having a dialogue with children,” she said. “But I am really a science person who wants to communicate science. I aim to create pictures in children’s minds that let them see the biology, the chemistry, the physics and how interconnected it all is.”

A passion for conservation and the desire to introduce scientific concepts in a lived-way led Bradshaw to her latest children’s book, The Great Lizard Trek. Illustrated by Norma MacDonald, an Aboriginal Yamaji artist, The Great Lizard Trek introduces children to the potential effects of climate change on Australia’s animals.

“Lizards are an ideal subject for children, especially dragon lizards. They have the same body temperature as us (not cold-blooded); drink by putting their foot in a puddle; walk on water and can change the sex of their offspring. Perfect, I thought.”

The benefits of reading to children are well established – research found that reading to children six to seven days a week puts them almost a year ahead of those who are not being read to – yet the number of children and adults reading for pleasure has dropped over the past decade.