Bee with a backpack...of the sensor variety.

Bee with a backpack…of the sensor variety.

By Emma Pyers

How do bees in the Amazon jungle compare to those in Tasmania? They get up earlier, for a start.

Paulo de Souza and his team have been tracking bees in the two regions using tiny backpack sensors as part of our Swarm Sensing Project to gather biological and ecological data to improve honey bee health.

The tiny backpacks are just a quarter of a centimetre square and are fitted to the back of the bees.

“We have already attached the micro-sensors to the backs of thousands of bees in Tasmania and the Amazon and we’re using the same surveillance technologies to monitor what each bee is doing, giving us a new view on bees and how they interact with their environment,” Paulo said.

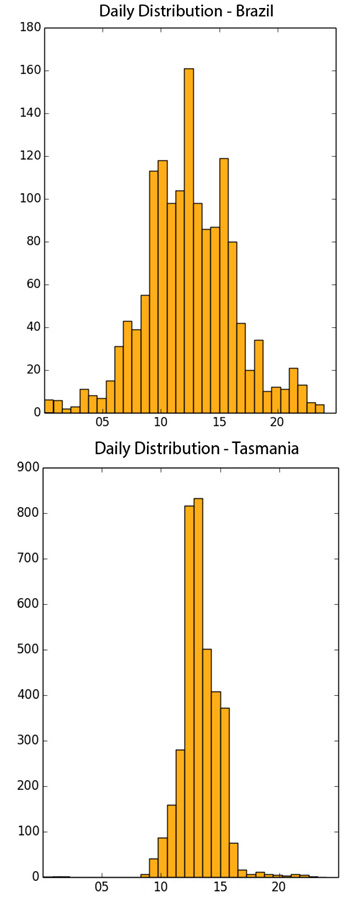

Daily distribution of bees in Brazil and Tasmania

Daily distribution of bees in Brazil and Tasmania (click for large version)

“Once we have captured this information, we’ll be able to model it. This will help us understand how to manage our landscapes in order to benefit insects like bees, as they play such a key role in our lives. For example, one third of the food we eat relies on bees for pollination, that’s a pretty generous free service these humble insects provide us!”

Early modelling has shown one notable difference between the bees in Tasmania and those in the Amazon; Amazon bees are up and about very early in the morning while Tassie bees prefer to wait until the day warms up before they leave the hive.

But finding out what time bees get out of bed is only a tiny part of what the research can show us. For example the research will also look at the impacts of agricultural pesticides on honey bees by monitoring insects that feed at sites with trace amounts of commonly used chemicals.

A global buzz in micro sensing

We’re working with the Vale Institute of Technology in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, on micro-sensory technology and systems (read more about what Vale is up to here).

Working with researchers across the globe has its unique challenges as well as its rewards, and it’s the physical challenges that have been the most interesting.

“As the Africanised honey bees were very aggressive, the hive was placed in an isolated area away from housing and domestic animals – and isolation meant working in densely vegetated areas,” Paulo explained. “We had to clear a path to the hive and we wore fully protective bee clothing which was tough given the extreme humidity and heat.”

The Brazilian media got a taste of what it was like to work in these conditions, when they suited up to interview Paulo and our colleagues from the Vale Institute of Technology about their work

Pressure from the press

Pressure from the press

The collapse in global populations

Bee health is important globally however, honey bee populations around the world are in danger.

Colony Collapse Disorder (CCD) – a phenomenon in which worker bees from a colony abruptly disappear – and Varroa mite are two major problems facing bee populations globally. While these two problems haven’t appeared in Australia, there is a very real risk. And what happens if it does? Catastrophe!

Check out this video where Peter Norris, Tasmanian beekeeper, describes his first hand experience with CCD while working in the United Kingdom.

So it’s a good thing our scientists, and their colleagues in Tassie and Brazil, are on the case.

To learn more about how we’re trying to save honey bees around the world tune into ABC Catalyst at 8pm tonight.

CSIRO’s Swarm Sensing Project is a partnership with the University of Tasmania and receives funding from Vale, a Global mining company.