Not this one. It’s the Atlantis Hotel in the Bahamas.

Wouldn’t it be good if there were a spare ecosystem we could try things out on before making a decision about how we use resources? Sadly, there’s no Earth II, but at least we have Atlantis.

No, not the fabled sunken city, but a marine ecosystem modelling tool that lets resource managers and coastal planners test drive their decisions before they commit to them in the real world.

We’ve developed a model that encompasses oceanography, chemistry and biology, and simulates ecological processes such as consumption, migration, predation and mortality.

The United Nations rated Atlantis as the best ecosystem model in the world for looking at alternative management strategies for fisheries, and regional versions are being used in management strategy evaluation for more than 30 ecosystems in a wide range of places.

Before models like Atlantis were available, decisions about resource use were made in isolation. We’d make our plans about things like fisheries or water quality based on what we knew about fisheries or water quality, rather than on their effects on the entire system. And decisions like these – that don’t look at the system as a whole, interdependent web – can often be on the wrong side of the law of unintended consequences.

So Beth Fulton got to work and created Atlantis.

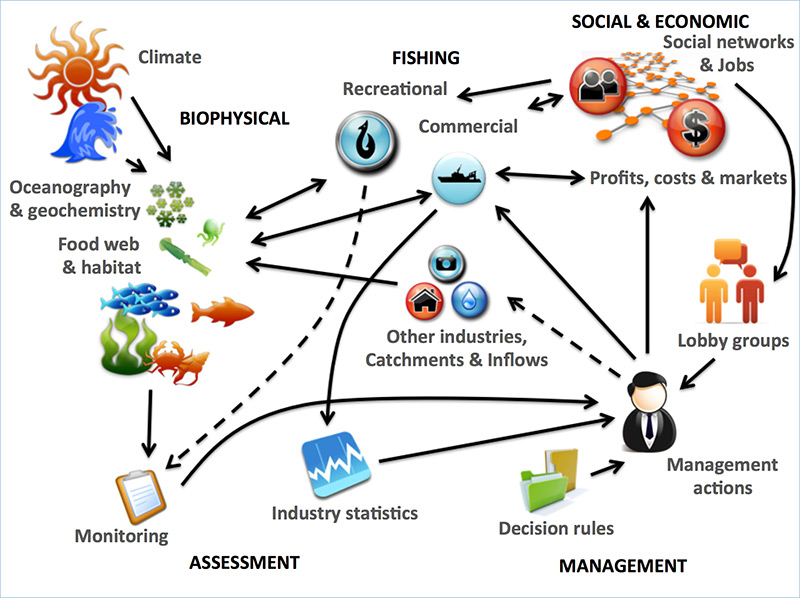

It gathers information including ocean currents, and the way the food system works, all the way up from phytoplankton – tiny plants that exist in oceans and underpin the marine food chain. They build up through to seaweed and sea grasses, different kinds of fish, to marine mammals like dugongs, sharks and seabirds. The modelling incorporates the ways people interact with the oceans and the Earth, and includes coastal industries such as ports and fisheries, along with the social and economic pressures that drive resource use decisions.

A conceptual diagram of Atlantis.

Atlantis has its longest usage history in south-eastern Australia. This is a marine area of about 4 million square kilometres, and home to Australia’s largest fishery. It’s also – literally – a hot spot for ocean warming. There the ocean temperature is rising faster than anywhere else, and the Australian current that extends down the eastern seaboard to Victoria is pushing further south to Tasmania.

The carbon dioxide that’s sucked up into the ocean is making the water more acidic. The balance of marine species, and their range, is likely to alter as the climate warms. We’ll still have fish and still be eating them, but there will need to be some major decisions made about how best to manage fisheries.

One of the beauties of the Atlantis model is that it can be re-calibrated with new data as the effects of warming oceans begin to be felt. This will be vital to making far-reaching decisions that can no longer be based on the old certainties.

For more on our work in oceans, head to our website.