A white shark swimming with a research tag

Swimming with the fishes: a tagged adult white shark

Given white sharks get the (sea)lion’s share of media attention, you may be surprised to learn that we don’t know a whole lot about them. Sure, we know some pretty cool stuff already: they give birth to live young, can swim over 60km an hour and are an apex predator. But because they swim huge distances and are lone travellers it’s hard to get to know them really well. Scientists love a challenge though, so, courtesy of their tireless efforts to study these great creatures, here are four facts you probably didn’t know.

1. There are two main populations of white shark in the Australasian region

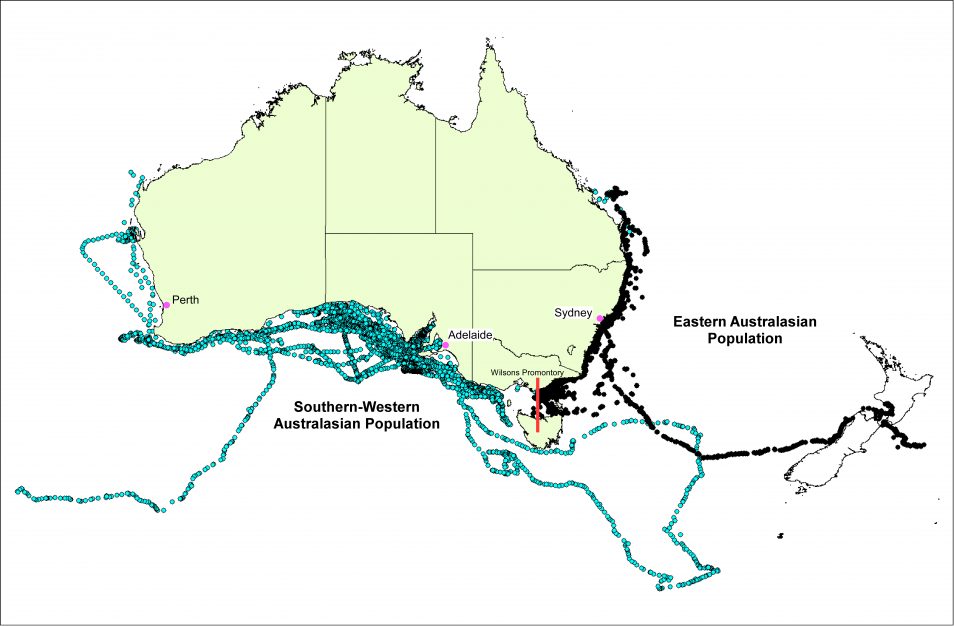

A map of tagged white sharks' movement showing two populations that don't mix

The two populations of white sharks rarely mix

Tagging data and genetic evidence suggests two populations of white sharks Carchardon carcharias (commonly known as the great white shark) exist in Australia: an eastern population ranging from Tasmania to central Queensland and across to New Zealand, and a southern-western population ranging from western Victoria to north-western Western Australia.

2. Until now, there were no reliable estimates of white shark population sizes in Australian waters

There’s a popular saying in the marine world: ‘counting fish is like counting trees, but you can’t see them and they move around all the time.’ Sounds impossible, right? Not for our scientists: in a world first we’ve used a unique combination of electronic tagging and tracking, collection of tissue samples, and a combined genetic and statistical technique called ‘close-kin mark recapture’ to estimate the Australian white shark populations. ‘Close-kin mark recapture’ means we compared the genetic data from juvenile white sharks to figure out how many shared a mother or father. This number can reveal the overall number of breeding adults: a smaller adult population means lots of half and full brothers and sisters, and vice versa. Through the juvenile’s DNA, we’re learning a whole lot about the adult population without having to track them down.

The only catch – you need to know where the cool kids hang (the nursery areas for juvenile white sharks) so you can tag them and collect samples. The eastern juveniles have a few choice locations but their southern-western counterparts are keeping tight-lipped about their favourite spots, meaning we couldn’t conduct the same study with them. Despite this, we were able to estimate the southern-western adult population size to be 1460 (with a range of between 760 and 2250).

But what of the eastern population? We estimate the total population to be 5,460 (with a range of between 2909 and 12,802). We’re not sure if this is historically high, low or somewhere in-between because we have nothing to compare it with, but at least we now have a starting point.

3. White sharks take a long time to mature

White sharks take a relatively long time to reach maturity — 12 to 15 years — which means they’re slow to reproduce. These are the badges of evolutionary honour a species gets to wear for being extremely successful. However, these same traits mean that if the number of mature white sharks dropped suddenly, the entire species could be under threat. Until now, we had no idea how many juvenile sharks survive to maturity, an important piece of the population puzzle. Another incredible thing our researchers have uncovered is the mortality rate of juvenile sharks in the eastern population. Using data from around 70 juvenile sharks fitted with an acoustic emitter we estimated that juvenile sharks had an annual survival rate of around 73 per cent.

4. More sharks in the water doesn’t mean more shark attacks

While it’s true the overall number of shark attacks has gradually increased in the past few decades in Australia, many different factors unrelated to shark numbers contribute to the overall increase in shark attacks. These include human population trends, changes in human population distribution and regional demographics, as well as variations in lifestyle and behaviour of people over time. However, clusters of shark attacks cannot be attributed to increases in human use of the ocean, or sudden increases in overall shark population size, because neither of these change over such short periods.

There are, for example, high human-use areas where white sharks are abundant but the incidence of shark attack is low. The drumline program in Western Australia revealed a significant number of tiger sharks present in coastal waters off Perth, yet no attacks have been attributed to this species in the area since 1925 according to the Australian Shark Attack file. Incidence and frequency of shark attacks may not relate directly to local shark abundance and cannot be used as a proxy for shark population trend.

So, what does all this new information mean? Now that we have a starting point for shark populations, we’ll be repeating the process over time to build population trends – a crucial step for developing effective policy outcomes for conservation and risk management.

Feeling fishy?