Astronomers are like explorers: they push boundaries, search uncharted territory and challenge conventional wisdom.

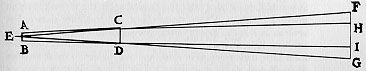

While Indigenous cultures around the world have been studying the heavens for millennia, modern astronomy was born in the 1600s when Italian astronomer Galileo Galilei looked at the stars through a telescope.

Galileo rocked the establishment when he challenged our understanding of Earth’s place in the Universe. Not a winning strategy in an era when the Church had the power to criminalise ideas and imprison anyone who publicly defied the order of things.

He courageously published his evidence, was found guilty of heresy and sentenced to life in prison but his legacy lives on and telescopes have become our eyes and ears on the Universe.

Telescopes have since been used to observe visible light from stars and, more recently, to detect radio waves and other types of electromagnetic radiation from space, transforming our understanding of the Universe.

Galileo’s telescope transformed our understanding of the Universe and today’s astronomers stand on the shoulders of visionaries like him and others who dared to dream and push boundaries. Image: ATNF CSIRO

A new telescope for a new era of discovery

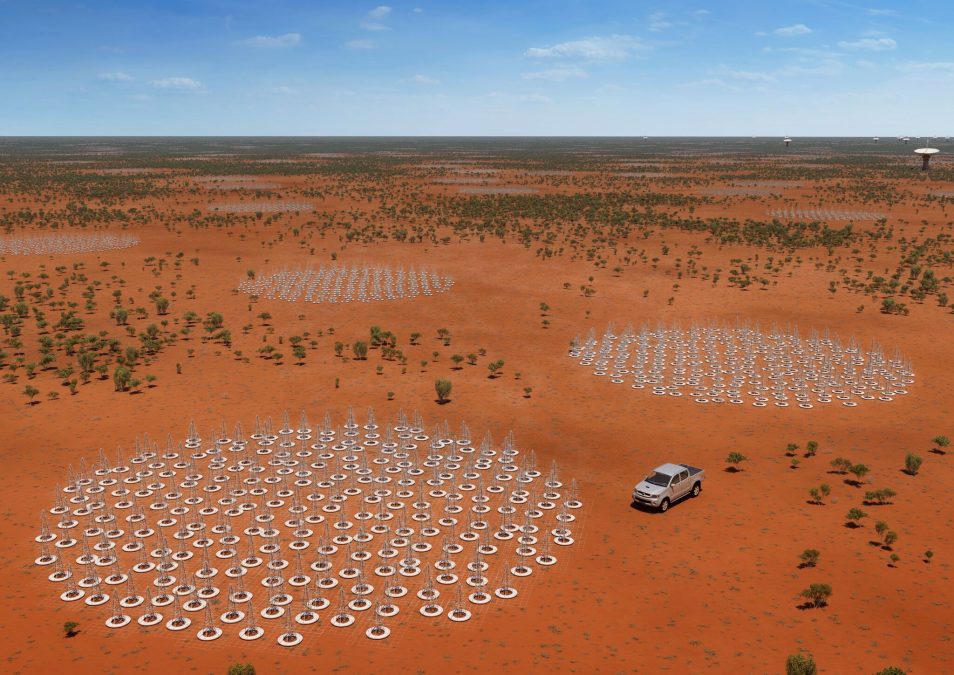

In the 1990s an international group of astronomers imagined a new telescope that could answer the biggest questions and solve the greatest science mysteries of our time. The instrument would have to be the largest radio telescope ever built and would require technology that didn’t yet exist.

Named the Square Kilometre Array (SKA), this new machine would not only require inventive engineering, science and technology, but a substantial financial commitment by multiple countries and cooperation across governments.

Could an international consortium come together and build this next-generation instrument?

Australia joined with Italy, China, Portugal, South Africa, the Netherlands and the UK to become the founding members of the SKA Observatory, with more nations to join. Image: SKA Organisation.

Taking the next steps to realise the SKA

This week the international radio astronomy community pulled off an impressive feat of science diplomacy with a gathering of Government Ministers, Ambassadors and high-ranking officials to sign a treaty establishing the Square Kilometre Array Observatory, an intergovernmental organisation committed to building and operating the SKA.

The ceremony was fittingly held in the country of Galileo’s birth, at Italy’s National Institute for Astrophysics.

Negotiation of this ‘SKA treaty’ has taken several years. At the same time, more than 1,000 engineers and scientists from 20 countries formed 12 international teams to design the telescope.

Once all the design packages are complete and approved, a review of the entire SKA system will take place before construction begins in 2020.

Construction of the SKA – at our Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory in Western Australia (like the artist’s impression above), and in southern Africa – is expected to begin in 2020. It will be the first global mega-science project hosted by Australia.

In its 50 years of operation, astronomers from participating countries will be able to study gravitational waves and test Einstein’s theory of relativity in extreme environments, map hundreds of millions of galaxies, and look for signs of life elsewhere in the Universe.

As well as making new discoveries, the SKA will drive technological advancement, inspire students into STEM careers, and open new areas of research.

I wonder what Galileo would make of this impressive machine and how far we’ve come – and will go – in understanding our place in the Universe?

We acknowledge the Wajarri Yamaji people as the traditional owners of the Murchison Radio-astronomy Observatory site.