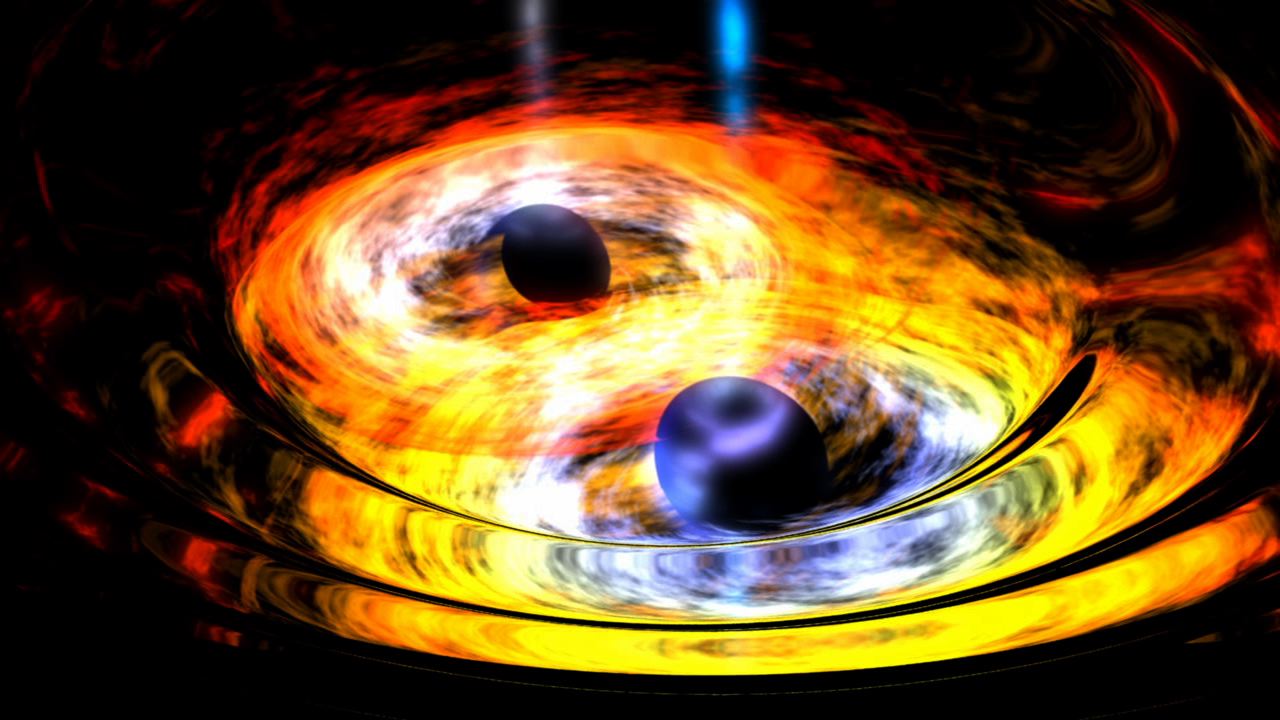

Two black holes are entwined in a gravitational tango in this artist’s conception. Supermassive black holes at the hearts of galaxies are thought to form through the merging of smaller, yet still massive black holes, such as the ones depicted here.

Image Credit: NASA

Astronomers using NASA’s Wide-field Infrared Survey Explorer (WISE) have spotted what appear to be two supermassive black holes at the heart of a remote galaxy, circling each other like dance partners. Follow-up observations with the Australian Telescope Compact Array near Narrabri, Australia, and the Gemini South telescope in Chile, revealed unusual features in the galaxy, including a lumpy jet thought to be the result of one black hole causing the jet of the other to sway.

The observations suggest that the jet of one black hole is being wiggled by the other. It is likely the two black holes are fairly close to each other and are gravitationally entwined. These findings could teach astronomers more about how supermassive black holes grow by merging with each other.

Almost every large galaxy is thought to harbor a supermassive black hole filled with the equivalent in mass of up to billions of suns. How did the black holes grow so large? One way is by swallowing ambient materials. Another way is through galactic cannibalism. When galaxies collide, their massive black holes sink to the center of the new structure, becoming locked in a gravitational tango. Eventually, they merge into one even-more-massive black hole.

The dance of these black hole duos starts out slowly, with the objects circling each other at a distance of about a few thousand light-years. So far, only a few handfuls of supermassive black holes have been conclusively identified in this early phase of merging. As the black holes continue to spiral in toward each other, they get closer, separated by just a few light-years.

It is these close-knit black holes, also called black hole binaries, that have been the hardest to find. The objects are usually too small to be resolved even by powerful telescopes. Only a few strong candidates have been identified to date, all relatively nearby. The new WISE J233237.05-505643.5 is a new candidate, and located much farther away, at 3.8 billion light-years from Earth.

Radio images built up using the six 22-metre antennas of the Australian Telescope Compact Array were key to identifying the dual nature of WISE J233237.05-505643.5. Supermassive black holes at the cores of galaxies typically shoot out pencil-straight jets, but, in this case, the jet showed a zigzag pattern. According to the scientists, a second massive black hole could, in essence, be pushing its weight around to change the shape of the other black hole’s jet.

The final stage of merging black holes is predicted to send gravitational waves rippling out through space and time. Researchers are actively searching for these waves using arrays of dead stars called pulsars in hopes of learning more about the veiled black hole dancers. Once such survey is being conducted by CSIRO’s Parkes Radio Telescope.