By Merrin Fabre

While some of us have hairy backs (not a good mental image) there are those in nature that are lucky enough to have exoskeletons made of nano-size photonic crystals: back bling.

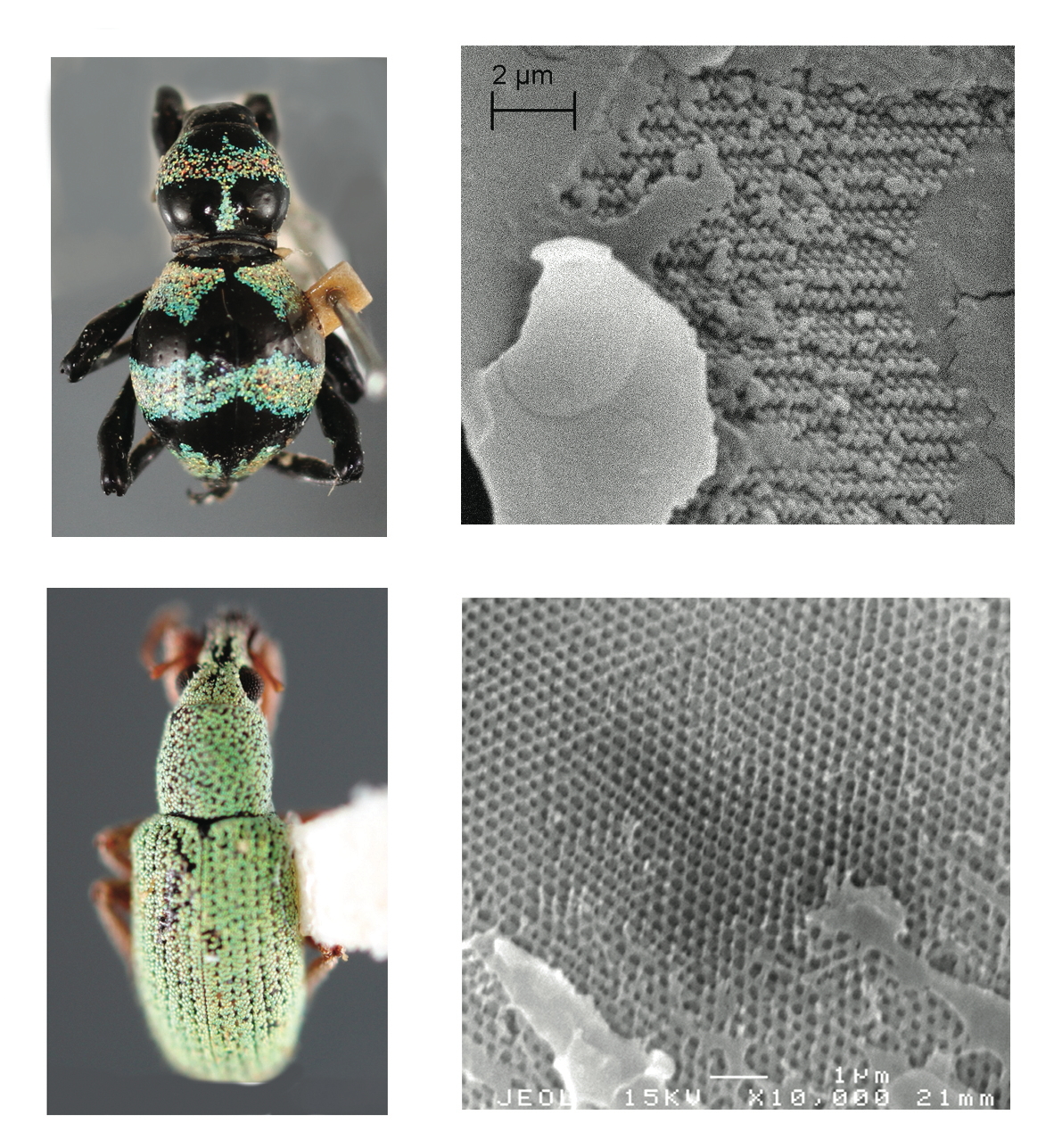

The lucky beetle – the opal weevil – has evolved to produce 3D crystals that can reflect light at any angle and produce bright, vivid colours that we see as metallic or iridescent.

Opal Weevil

“Nature has been producing nanostructures, such as the weevil’s crystals, since the dawn of time”, says Amanda Barnard the leader of our Virtual Nanoscience Laboratory.

“I think is it generally assumed that nanomaterials are a relatively new phenomenon but some nanoparticles have been present in animals and minerals for millions of years and are a natural occurrence.”

Amanda, along with Haibo Guo, has just released a book about nature’s nanostructures.

Here is a video of Amanda talking about her work.

The book, Nature’s Nanostructures, looks at naturally occurring nanostructures and it covers the scientific spectrum including entomology, geology, astronomy, physics, chemistry, molecular biology and health.

“There is a variety of naturally occurring nanoparticles and nanostructures and nature has been using them for functional technology,” Amanda says.

An example of this is birds that recognise weak geomagnetic fields. The Earth’s magnetic field provides and important source of directional information for many organisms, especially birds. The book looks at magneto-reception found in the beaks of homing pigeons and how the nanostructures in their beaks work as an efficient magnetic field amplifier.

So, once again scientists are looking to nature to find out how things are done so that we can eventually copy it.

“By studying how these nanomaterials are naturally produced we will be one step closer to being able to replicate these materials in a lab environment and exploring their potential applications in science and industry,” says Amanda.

Nature’s Nanostructures is available from the Pan Stanford Publishing site.