CSIRO researchers are using a world-renowned program to make maps of the future, to predict how climate change will affect our oceans and devise strategies to minimise its impacts. Marine modelling is a way of using scientific information to decode what is happening in the real world, and predict what the future might look like.

Dr Beth Fulton, a CSIRO science fellow and recipient of the prestigious Science Ministers Prize and Pew Fellowship, is a world leader in marine ecosystem modelling, and the creator of the Atlantis modelling tool.

“It’s about making a little version of the world inside a computer and all the different parts that come together, rather than just focusing on one part or another,” Dr Fulton explains.

It may sound complex, but Dr Fulton says we all unconsciously use modelling.

“You don’t put your hand on a hot heater because in your head you have a little model that says if I do that I’ll get hurt,” she says.

Previously, individual components of an ecosystem, such as water quality or fisheries, were each examined in isolation. Dr Fulton started developing the tool 15 years ago because there was a need to see how different parts of an ecosystem were influencing each other.

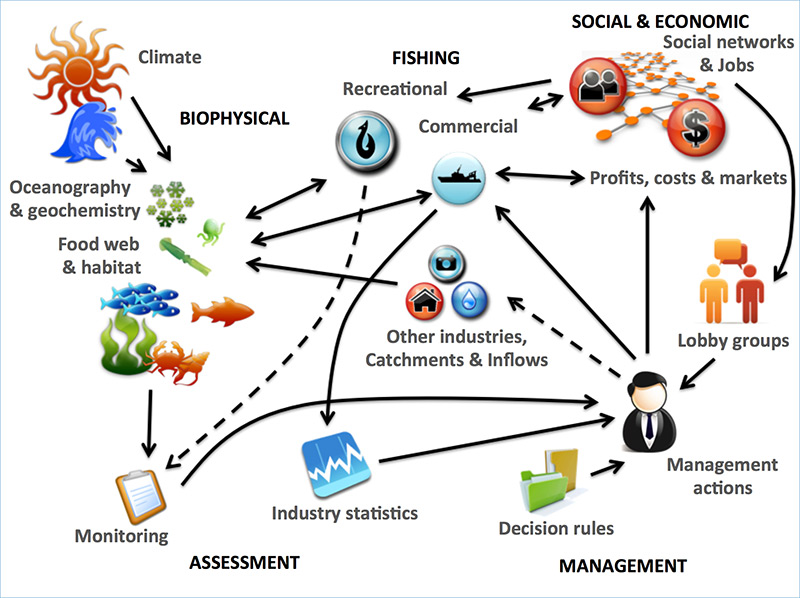

Atlantis has grown to include some of the major climate drivers. It gathers information including ocean currents, and how the food web is built up starting with phytoplankton – tiny plants that exist in oceans and sustain the marine food web. They build up through to seaweed and sea grasses, different kinds of fish, to marine mammals like dugongs, sharks and seabirds. The modelling gauges the ways people interact with the oceans and the earth. The modelling framework also includes coastal industries including ports and fisheries as well as social and economic drivers.

Dr Fulton and her team are the number crunchers, pulling all the information together. “Using maths as a language to describe the world is what we do, and then we effectively make science-based computer games,” she says.

Atlantis conceptual model

Atlantis is used in 26 ecosystems, primarily in Australia and the US. It also has a presence in Antarctica, South America, Africa and Europe. A 2007 United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation report rated the Atlantis system the best in the world for considering alternative potential futures for fisheries and marine ecosystems.

Using this modelling can help coastal communities make decisions about the way they live. It can also help industries, such as fisheries, oil and gas, shipping, ports, biosecurity and tourism, make decisions taking into account economic and social factors.

This more holistic approach is known as ecosystem-based management.

Our oceans are an economic asset. In hard dollar terms, the oceans are worth $45 billion to Australia, according to the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Dr Fulton’s own modelling suggests once you take into account all the other things that marine ecosystems do for us, like oxygen production, nutrient cycling and flood prevention, the figure rises to $700 billion.

Dr Fulton says the oceans are also close to people’s hearts. “It’s a part of our identity.”

Ocean hot spots

Atlantis has its longest history in south-eastern Australia – an area of about 4 million square kilometres, and home to Australia’s largest fishery. This is one of the world’s hot spots for ocean warming. Here, the ocean temperature is rising faster than anywhere else because the Australian current that extends down the eastern seaboard is pushing further south to Tasmania. Previously, it stopped at Victoria.

The carbon dioxide that gets sucked up into the ocean is making conditions for the animals living there more acidic. Animals subsequently don’t grow as much, and are more vulnerable to predators. Work by researchers at James Cook University shows it even affects how they think.

“They don’t realise that they shouldn’t be attracted to their parents,” Dr Fulton says. “They don’t realise that they should be afraid of predators.”

Winners and losers

A very likely outcome of climate change is that some species of fish will not grow as large. This will radically change the structure of ecosystems, with the predator and prey trading places.

As it becomes hotter, the physiology of fish changes. In the ocean, big things eat little things. Think of all those classic images of little fish being gobbled up by bigger fish. But this relationship is becoming more complex.

A baby fish might grow into a big predatory fish. But a baby fish is also prey to species that it could actually eat – if it survived long enough to become an adult!

Take the flathead of south-eastern Australia. If its maximum size reduces by as little as 5 per cent in the next 50 years, it’s a win for the barracouta, jellyfish and cephalopods like squid and octopuses.

“The flathead becomes a tastier prey that’s easier to catch,” Dr Fulton says.

For the barracouta, its survival might be enhanced. Large flatheads eat small barracoutas. If the flatheads stay small, they remain prey for the barracouta for longer. Further boosting their prospects is the existence of fewer large flatheads to eat baby barracoutas.

So while the flathead is shrinking in the physical sense, so, too, is its population – by as much as 20 to 30 per cent. Meanwhile, the barracouta population is getting larger.

“Climate change is already affecting the south east, but it’s going to affect it more and more into the future,” Dr Fulton says. “And that will be seen on dinner plates across the south-east of Australia.”

But it’s not all bad news. “We’ll still be eating fish in 2050 or 2100, or even further into the future, but exactly the kinds of fish will probably have to change quite a lot to remain sustainable.”

CSIRO is staying across the issue, to provide the best information so people can change their behaviour over time.

Sustainable fishing

The modelling also suggests that fairly large vessels will likely be the most effective in the future, because they can shift with the fish. That means they’re not tied to one place and depressing the local stock. They’re moving with the healthy population.

However, smaller vessels tied to a home port, are likely to be the most impacted by 2050. They can’t move as far or as fast as the fish. And social connections tying them to one port and the size of their boats mean they can only fish in nearby regions. Anchored in this way, people have no choice but to stay there, potentially causing local depletion.

“Under those conditions they can actually present an ecological threat to the system,” Dr Fulton says. This does not mean we should give up on Australian fisheries. Instead it highlights the importance of using up to date information as the system changes. Australian fisheries have put considerable effort in to achieving sustainability and are already investing in finding the best ways forward.

CSIRO, The Australian Fisheries Management Authority, the Fisheries Research and Development Corporation, theGordon and Betty Moore Foundation, the David and Lucille Packard Foundations and the Department of the Environment have all contributed to funding the Atlantis model.