A chestnut teal (above) and a grey teal (below). The male chestnut teal is something of a peacock among ducks. Image credit: (Top) Steve Kelling, (below) Leo via Flickr http://www.flickr.com/photos/0ystercatcher/3230589301/

There’s a Dreaming story told by the Bardi people of the Kimberley in Western Australia about how birds got their colours:

In the Dreaming all birds were black. One day Dove hurt his foot on a sharp stick and developed an infection. As he lay dying the other birds gathered around to help – all but Crow. Parrot saved Dove’s life by using her sharp beak to burst the wound on his foot. Colours sprang from the wound, painting Parrot and the surrounding birds in many different colours and patterns. Having refused to help, Crow’s feathers stayed black.

Genomics also has a story to tell about the colours of Australia’s birdlife. Take Australia’s grey teals (Anas gracilis) and chestnut teals (Anas casanea). They’re close cousins, sharing a common ancestor very recently in evolutionary terms – probably well within the last 2 million years. The females of both species and male grey teals are a dull grey, but male chestnut teals are colourful.

We can recognise grey teals and chestnut teals as two different species by their feathers and by the different environments in which they live. But this is like looking at the universe through binoculars – you don’t get the whole picture. To understand more we need to look at these ducks‘ DNA using the molecular biologist’s answer to the Hubble Telescope: genomics.

It turns out that the genomes of these two ducks are very similar, until we look at a particular area on one of the sex chromosomes.

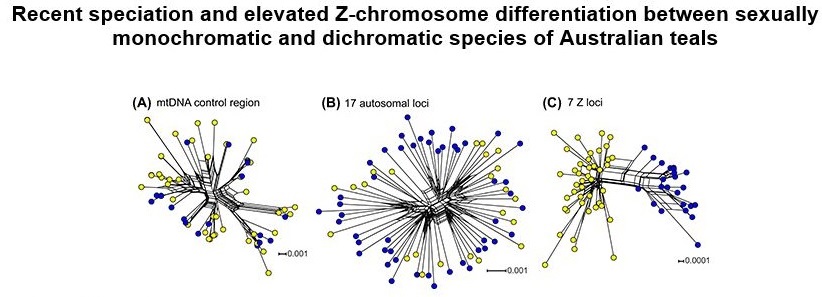

These network diagrams (taken from the Journal of Avian Biology) show genomic differences among the two species. Yellow circles are grey teals. Blue circles are chestnut teals.

Journal of Avian Biology28 SEP 2015 DOI: 10.1111/jav.00693http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/jav.00693/full#jav693-fig-0002

The networks on the left and in the middle show there are no particular differences between grey teals and chestnut teals when looking at a wide sampling of their genomes.

The network on the right, however, shows grey teals and chestnut teals form very separate groups when looking at genomic differences on the Z chromosome, which is one of the sex chromosomes of birds. (This suggests we could take a closer look at this region of a bird’s genome for genes to do with colour and plumage.)

These two species of ducks have evolved from a common ancestor because something happened to cause that ancestor to give rise to two different species – to speciate. According to Dr Leo Joseph, Director of our Australian National Wildlife Collection, this research shows us how the many-times-great grandparents of these two ducks might have parted ways.

“We’re pretty sure that the common ancestor of these ducks was grey, both the male and the female. Sex chromosomes seem to have played an important part in speciation in this case but also among birds in general.

“It’s important to solve mysteries like this about the relationships between different birds as it gives us another piece in the larger puzzle of describing, understanding and protecting Australia’s biodiversity.”

Much of what we know about Australia’s biodiversity, and what we will come to know in the future, is thanks to natural history collections like our Australian National Wildlife Collection.