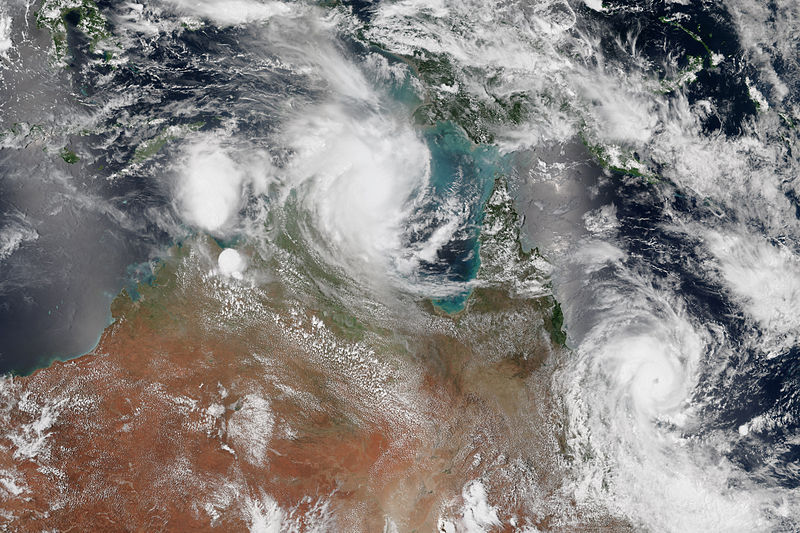

Within 6 hours, Northern Australia was battered by two potent tropical cyclones on the same day in February 2015. At 2 a.m, Cyclone Lam made landfall 400 km east of Darwin. At around 8 a.m, Cyclone Marcia made landfall near Rockhampton. Image: Suomi NPP Satellite

Updated 2 March 2021

Tropical Cyclone Idai hit parts of southern Africa in early March 2019. The Category 3 cyclone reached wind speeds of over 205 km/h and caused widespread flooding and mudslides. The damage was immense. With a suspected death toll of over 1000 and its damages costing affected countries over $7million USD, Tropical Cyclone Idai is, according to Clare Nullis from the UN’s weather agency, “Shaping up to be one of the worst weather-related disasters ever to hit the Southern Hemisphere.”1

Back home, tropical cyclones are an ongoing threat during our cyclone season, which generally lasts from November to April. On average, the Australian region experiences 11 cyclones a year, although typically only four to five of these cyclones will reach land.

We’ve got some answers to a few questions you may have about cyclones.

1. What causes tropical cyclones?

Several conditions must be met for a cyclone to form, including thunderstorms over a warm body of water and little change in the wind with height.

Warm and humid air from a warm ocean (typically, at least 26.5 °C in the current climate) rises, resulting in a low pressure system. Air rushes in to fill the gap but due to the spin of the Earth, it starts spiralling around the low pressure and flows upwards near the centre. Due to the dependence on the Earth’s spin, tropical cyclones typically do not occur within about 5 degrees of the equator.

2. Can tropical cyclones be predicted?

The ability to predict tropical cyclones has radically improved due to developments of global climate models. In Australia, the Australian Community Climate and Earth-Simulator (ACCESS) model is used alongside global models to predict cyclone tracks and intensity.

In the last decade, the accuracy of tropical cyclone forecasts has improved measurably—most notably cyclone track forecasts, which allow for better planning of emergency events and decision making. However, forecasting tropical cyclone intensity, including rapid intensification, is an ongoing challenge and remains an active area of research.

ACCESS was used to predict the path of Tropical Cyclone Yasi, which crossed the coast of North Queensland in 2011. This allowed the community, industry and emergency management agencies to make decisions and plan seven days ahead of the event.

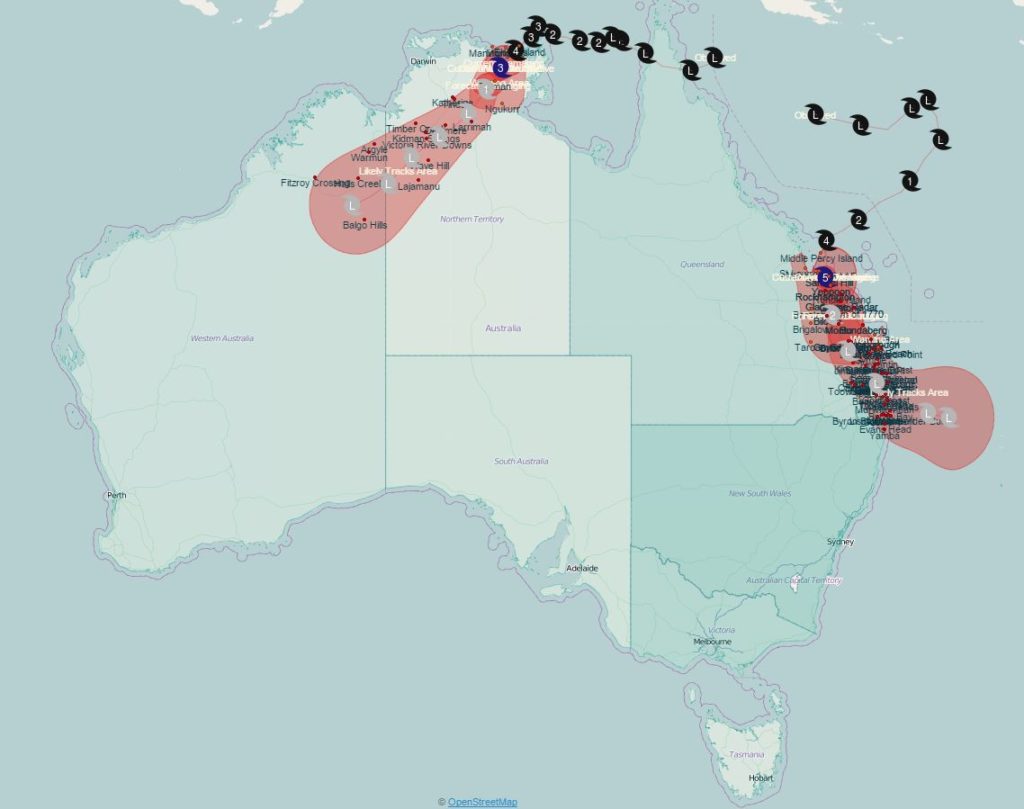

Once predicted, we can respond to cyclones with ERIC, our emergency response tool. Here, it displays paths of TC Marcia and Lam from the photo above.

3. Has the frequency of tropical cyclones changed?

Research has shown a statistically-significant downward trend in the annual number of tropical cyclones in the Australian region over the period extending from 1981/82 to 2017/18. The reasons for this downward trend are still being determined, but are likely to be due to a combination of both natural variability and longer-term climate change.

The Bureau of Meteorology’s satellite record is short and there have been changes in the historical methods of analysis. Combined with the high variability in tropical cyclone numbers and natural variability such as the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, this means it is difficult to draw conclusions regarding changes.

However, it is clear that sea surface temperatures off the northern Australian coast have increased—part of a significant warming of the oceans that has been observed in the past 50 years due to increases in greenhouse gases. Warmer oceans tend to increase the amount of moisture that gets transported from the ocean to the atmosphere, and a warmer atmosphere can hold more moisture and so there is a greater potential for intense rainfall events.

4. Will the frequency of tropical cyclones change in future?

The underlying warming trend of oceans around the world, which is linked to human-induced climate change, will tend to increase the risk of extreme rainfall events in the short to medium term. Studies in the Australian region point to a potential long-term decrease in the number of tropical cyclones each year in future, on average.

On the other hand, there is a projected increase in their intensity. In other words, we may have fewer cyclones but the ones we do have will be stronger. So there would be a likely increase in the proportion of tropical cyclones in the more intense categories (category 4 or 5). However, there is large uncertainty in these projections due to challenges associated with modelling tropical cyclones in coarse-resolution climate models.

We must prepare and plan for the many and varied impacts of cyclones. For instance, in far north Queensland, cyclones affect rainforest canopy cover, putting more pressure on endangered cassowary populations who depends on rainforest fruits to survive.

5. What are the impacts of tropical cyclones?

The most severe impacts of tropical cyclones are not just due to strong winds, which slow down once they reach the land, but are also due to heavy rains and storm surges.

Today, coastal flooding is often caused by storm surges, which occur when strong onshore winds from cyclones combine with their low pressure to elevate sea levels and drive water on to land. Storm surges can be particularly dangerous when they coincide with high or king tides.

Cyclone Yasi in February 2011 was one of the most destructive cyclones to hit Australia. Classified as a Category 5 cyclone, Yasi caused $1.4 billion worth of damage, according to the Insurance Council. Yasi destroyed infrastructure, flattened crops and caused extensive damage to corals on the Great Barrier Reef, but no lives were lost.

Both Cyclone Oma and Cyclone Idai were Category 3 when they hit the coasts of New Caledonia and Mozambique respectively in early 2019. However, Oma caused coastal damage and flooding, but Idai created an ‘inland ocean’ in Mozambique leading to the death and displacement of thousands of families.

6. How will the impacts of tropical cyclones change in future?

With rising sea levels and a projected increase in cyclone intensity, there is likely to be an increased risk of coastal flooding, especially in low-lying areas exposed to cyclones and storm surges. For example, the area of Cairns’ risk of flooding, by a 1-in-100-year storm surge, is likely to more than double by the middle of this century. Extreme rainfall from tropical cyclones is also likely to increase.

Banana plantations were flattened after Tropical Cyclone Larry in Queensland in 2006. Photo: Bureau of Meteorology

7. How can we adapt to expected changes?

In the longer term, better planning and design can help protect homes and infrastructure. This could include making sure new constructions have floor heights above sea level and lower floors are made with flood tolerant materials. Planning codes also need to prevent new development in flood prone areas.

Governments are now taking account of changes in climate and sea level through their planning policies. Just as the building codes and rules for Darwin changed in the wake of Cyclone Tracy, so they should now be re-assessed for each region and locality in Australia to take account of climate change.