Investigator has returned to the East Australian Current to grapple with the challenges of maintaining IMOS deep water moorings.

Picture the scene. You’re standing on the gently rocking deck of a research ship in the middle of the ocean trying to shoot the top of a 4km long deep water mooring with a grappling hook so you can start hauling it on board to download the data it’s collected over the past 18 months.

Welcome to the world of IMOS deep water mooring research!

Could you hit a float at 20 paces with a grappling hook?

IMOS stands for the Integrated Marine Observing System. Since 2006, IMOS has been operating a wide range of observing equipment throughout Australia’s oceans to measure long-term changes in our oceans and climate. The Marine National Facility research vessel, Investigator, is currently at sea on a voyage in collaboration with IMOS to maintain a line of moorings in the East Australian Current (EAC) off the Queensland coast.

We join three scientists on board – Ana Berger, Paula Conde Pardo and Quran Wu – for the story of grappling with IMOS deep water moorings and find out what gets people clapping at sea.

Setting sail for science

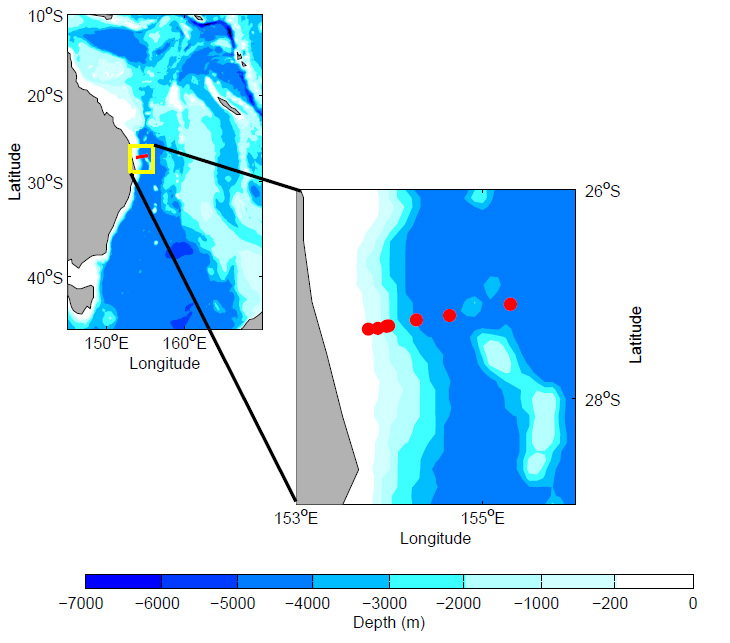

This is the third IMOS voyage dedicated to investigate the EAC, an important boundary current that transports heat to southern latitudes. The EAC sets the whole structure of the Tasman Sea and influences our climate, the ecosystem, commercial and recreational fishing, and much of what we see on the coast. To study its speed, structure and variability there are six moorings located in line off the coast. Each mooring collects data from the whole water column and the longest is 4800m long. As a support, we make Conductivity-Temperature-Depth (CTD) profiles before recovery and after redeployment of the moorings. These measurements also include the sampling of oxygen, salinity and nutrients.

Location of IMOS deep water moorings in the EAC.

The work in a mooring voyage is mostly during the day. It generally starts at 7:30 am and can last until late in the evening. This all depends on the weather and the conditions in which the mooring is found. There are many challenges in mooring management, including the dreaded ‘wuzzles’ (tangles in the cable) or bird nests of fishing line that are sometimes attached to it.

Even if the weather is generously warm and the ocean very calm (which has been happening frequently) the voyage is always busy for the crew who work the ship in shifts. Keeping everyone happy and healthy is a priority on the ship and there is nothing like a colourful icy pole to refresh those working the day shift!

Some have also discovered another challenge while working on deck – attack by kamikaze flying fish!

Kamikaze! Another reason to wear your hard hat on deck!

Mooring recovery

Mooring recovery is a complex process. Once the ship is on station in just the right spot (not always easy to achieve on the open ocean), a signal is sent to a special piece of equipment at the bottom of the mooring line that releases the whole mooring from the anchor on the sea floor.

After the mooring is released, many curious pairs of eyes on the bridge scan the ocean surface for the little yellow floats on the mooring line as they pop up. A mooring expert guy (a technical term) then shoots a grappling hook to it. The line is then tied to the ships winch and slowly pulled on board over many hours. The ships mooring crew on the deck does most of the recovery work. The scientists are in charge of bringing the instruments into a well-deserved warm bath where they are calibrated until the data is downloaded.

The challenge for the oceanographers then becomes decoding 18 months of fresh data to help inform understanding of the variability in the EAC.

Mooring deployment

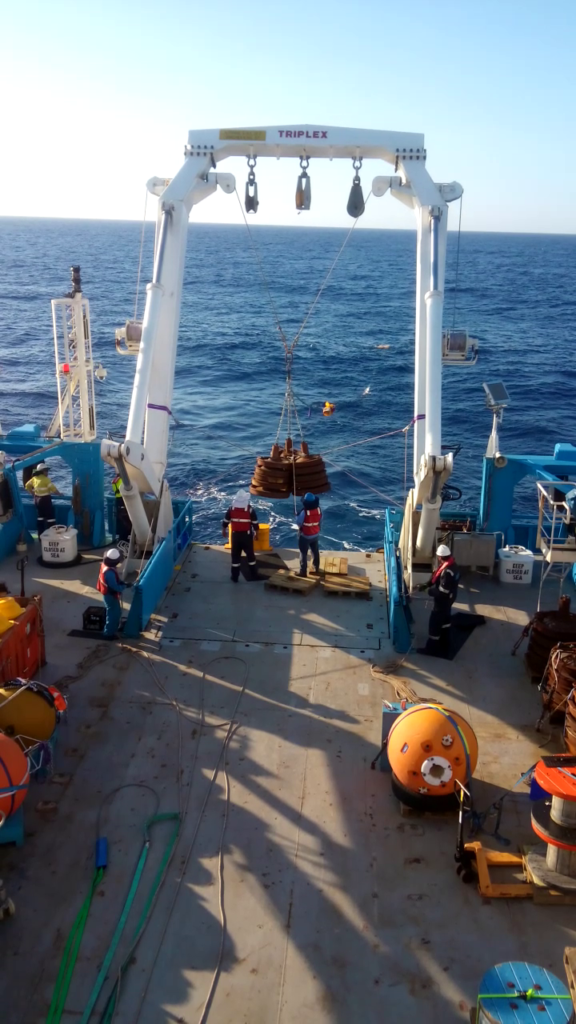

Mooring deployment is like the recovery in reverse. New instruments are ready to dive again in the deep waters of the Pacific Ocean to record what’s happening in the waters of the EAC. The science teams job in this process is to bring the instruments to the deck in perfect order. As the mooring is deployed, we create a beautiful tail of yellow floats hanging from the back of the ship across the surface of the ocean. The last things that we hang from the line are the release, which will allow us to recover the mooring next time, and an anchor made up of old train wheels which weigh 4.5 tonnes. This anchor is tied to a parachute that helps it to sink gently to the bottom.

The most important part of a deployment is to drop the mooring in the right spot, especially when you’re operating on the edge of the continental shelf. If you’re not on target, it can end up in water that is too deep or too shallow. Factors like currents and wind make anchor deployment an exact science to ensure it lands in the right position.

Anchors away! 4.5 tonnes of train wheels anchor moorings to the sea floor.

The crew of Investigator are amazing in the precision with which they manage these operations and all the deployments have been on target. I think there’s a sense of excitement and achievement from all to have the instruments gently dive up to 4800m to their correct positions on the ocean floor. Finishing a deployment always makes you feel like clapping! Some members of the voyage are searching for the appropriate piece of music that will be played for the last deployment.

It’s been a really successful voyage and the science team has enjoyed every moment of learning and discovering. Importantly, the hard work is always balanced with down time to relax, chat with colleagues and crew, exercise, read and watch movies. We even managed to get into the spirit of the Melbourne Cup with a bit of creative hard hat artistry!

If you’re looking for the data that is collected, check out the Australian Ocean Data Network (AODN) Portal. The Marine National Facility policy requires that data gathered on the ship is made publicly available and this allows marine and climate scientists, and other users to discover and explore IMOS data streams coming from these mooring networks.

To find out more about other important marine research enabled by Investigator, visit the Marine National Facility website.