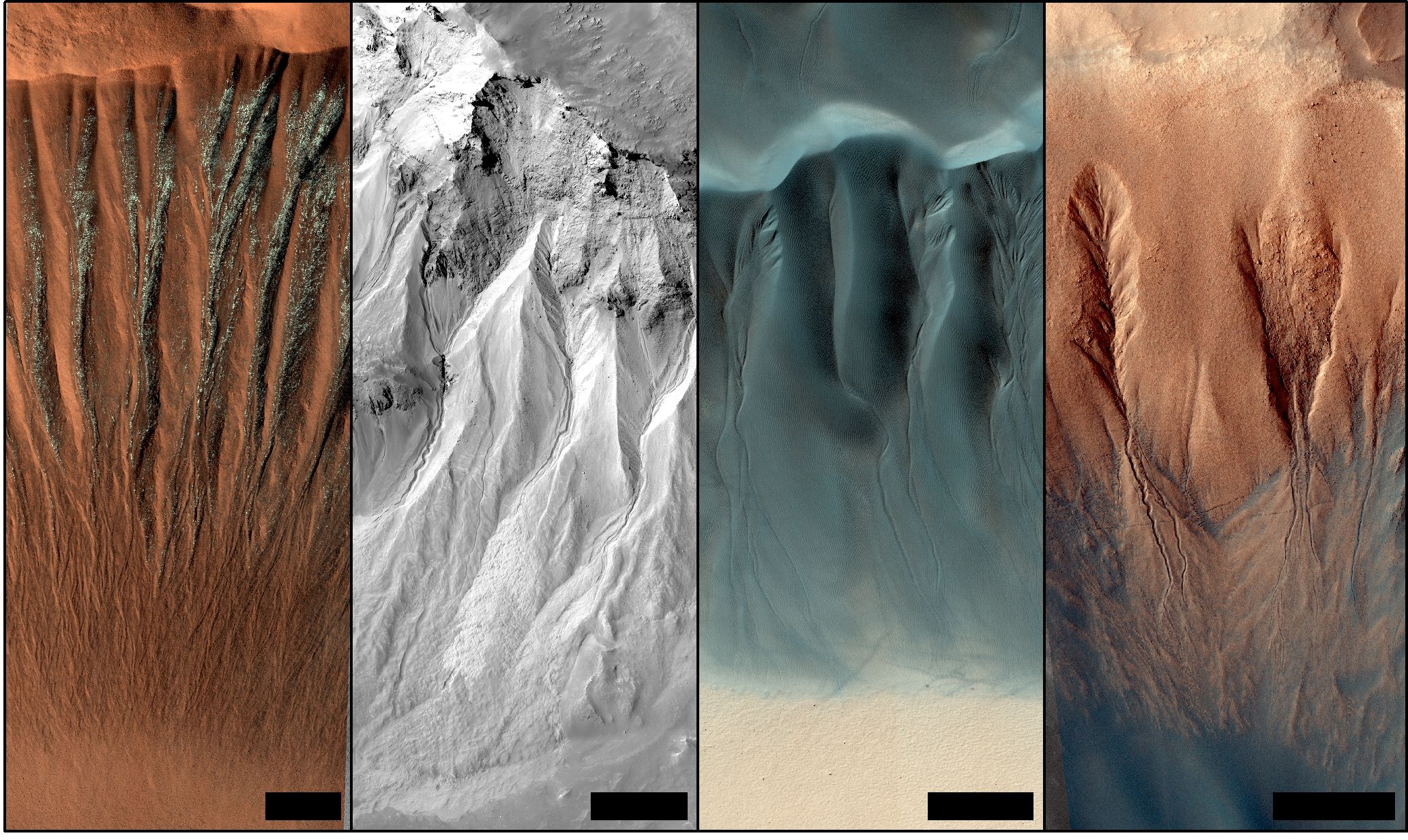

Close up of Martian gullies. Each scale bar is 300 metres long. Credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona

For decades scientists have been staring into space looking for signs of life on Mars. Even the landforms on the Red Planet were thought to be dead. Now, thanks to 19 years of observations of Martian gullies, researchers have discovered they’re actually being changed by erosion.

“Mars is not a dead planet,” British researcher Dr Susan Conway from the University of Nantes in France said.

Dr Conway told an international symposium in Townsville that Mars is an active planet.

“Repeated observations have now revealed that sediments are being transported in gullies today,” she said.

Gullies were first reported on Mars in 2000. Initially they were thought to have been caused by groundwater flowing from under the Martian surface.

“Mars is believed to have been hyper-arid for the past billion years. The possibility that aquifers could exist on Mars, providing a potential oasis for life, was big news,” Dr Conway told the International Symposium on Gully Erosion.

Now the truth is out that sediments are moving in the gullies. They tend to occur at the coldest times of year when temperatures can be more than 100 degrees Celsius below freezing. This has led scientists to think that liquid water is not involved. Instead it points to carbon dioxide ice which changes directly from ice to gas (known as sublimating) as the culprit.

“In our recent work, my collaborators and I have been further exploring the role that carbon dioxide ice could play in mobilising sediment flows in Martian gullies.”

Back down to Earth

Gully erosion causes sediment to be delivered to rivers and other bodies of water. This natural hazard can be accelerated by climate change, extreme events and human land-use.

Unfortunately, we’ve seen this increase in sediment flowing into the Great Barrier Reef. This is a concern because it can affect the water quality in the area resulting in damage to inshore coral reefs and seagrass beds.

Dr Scott Wilkinson is one of our researchers who organised the symposium. He researches the sources of river basin sediment and nutrient loads, their causes and how to manage them. His work has included defining the importance of gully erosion in tropical rangelands which drain to the Great Barrier Reef.

Heavy rain around North Queensland in February 2019 caused many gullies to erode, removing soil from grazing land and elevating sediment loads in the Burdekin and Bowen Rivers, where they come together is shown in this photo. Credit: Matt Curnock, CSIRO

Dr Wilkinson designed the catchment model used to report the effectiveness of public investments in reducing pollutant loads to the Great Barrier Reef lagoon.

“On Earth, gully erosion indicates an imbalance between the erosive power of runoff and the resistance offered by vegetation. Improving Great Barrier Reef water quality is one important application for this knowledge,” Dr Wilkinson said.

“Susan’s work with gullies on Mars demonstrates the rapid advance in technologies now being applied to investigate and monitor gully erosion. And this symposium is helping to get new approaches into more hands.”

We organised with symposium with our collaborators to bring together experts from Australia and around the world to connect people working in the reef catchments with expertise from around the world.

“Sharing results of scientific studies in this symposium, and bringing together different disciplines to learn from each other, is how we can improve management of gully erosion across the world, and beyond,” Dr Wilkinson said.