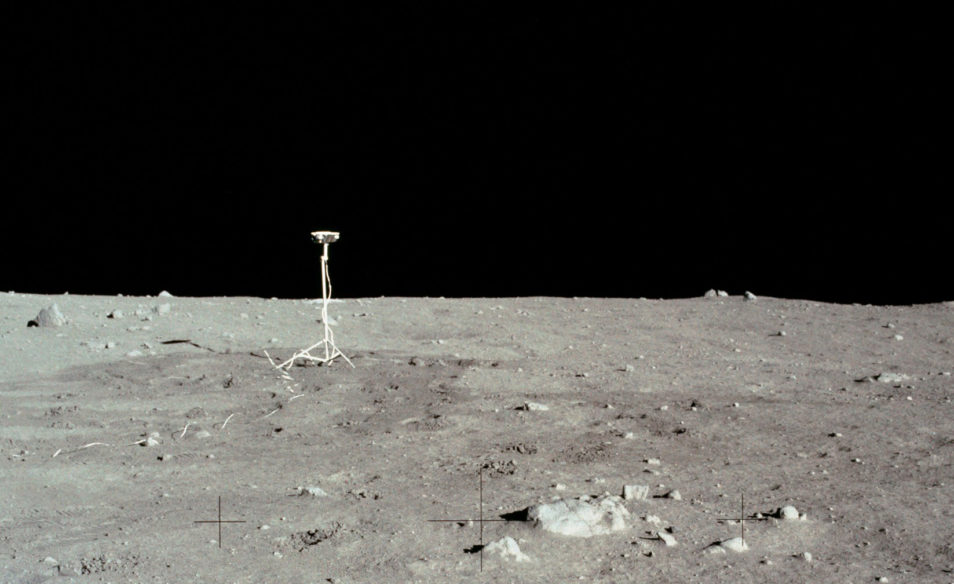

Feeling lonely? The TV camera from Apollo 11 remains on the moon. Credit: NASA.

This week we donated Australia’s official copy of the 1969 Apollo 11 Moon landing TV broadcast to the National Film & Sound Archive (NFSA) for their safekeeping.

It’s one of three archive-quality copies produced by NASA and the only one outside the USA. So how did this important piece of history make the epic journey from the Moon’s surface to us, then on to the NFSA? It’s a long story…

Lights, Camera, Apollo!

The Apollo program was the USA’s $25 billion bid to reach the Moon.

Every gram on Apollo 11’s lunar module had to be accounted for. Keeping flight weight down was critical. So much so that the astronauts didn’t have seats! (Talk about doing it for the ‘gram).

But NASA’s director of Flight Operations during the Apollo program, Christopher Kraft, recognised the importance of broadcasting the event.

“I told them to go ahead and figure out how we can take [the television camera] along,” he said.

NASA didn’t know if sending a TV signal 384,000 kilometres back from the Moon was even possible. So the broadcast had to share bandwidth with other data signals.

Neil Armstrong practises using the specially built Apollo 11 TV camera before the mission. Credit NASA.

Thankfully it was possible. 600 million people watched those first steps on the Moon. Incredibly, that broadcast all came from one 66-centimetre radio dish on top of the lunar module. It used just 20 watts of power – that’s the same energy output as two standard LED light bulbs!

But you won’t find the camera that captured Neil Armstrong’s famous first steps anywhere on Earth. It’s right where Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin left it. Attached to a tripod standing on the Moon. Bringing back Moon rocks and other samples meant as much equipment as possible had to be left behind. That included the Apollo 11 TV camera.

Behind the scenes of the footage that stopped the world

Three facilities proved critical to receiving the Apollo 11 moonwalk broadcast and sending it around the world: NASA’s own facilities in Goldstone, California and Honeysuckle Creek, near Canberra – as well as our Parkes radio telescope.

The Parkes observatory had served as the model for NASA’s Goldstone dish. Both were 64 metres across and could detect and receive weaker signals than smaller antennas. This meant that during the tightly-scheduled first moonwalk the astronauts didn’t have to spend valuable time setting up a large antenna to make the TV broadcast possible.

For the first nine minutes of the broadcast, NASA switched between the signals from its facilities at Goldstone and Honeysuckle Creek. The latter capturing the first foot-step on the Moon.

Chief of the CSIRO Radiophysics Division, Dr Edward ‘Taffy’ Bowen, with Dr John Shimmins, deputy director of Parkes Observatory, in the control room watching the moonwalk (21 July 1969).

The signal being received by our Parkes radio telescope was then used to share, as Houston said, the “best images yet” for the remainder of the two-and-a-half-hour broadcast to the world. This was, in part, due to its larger surface area and greater sensitivity.

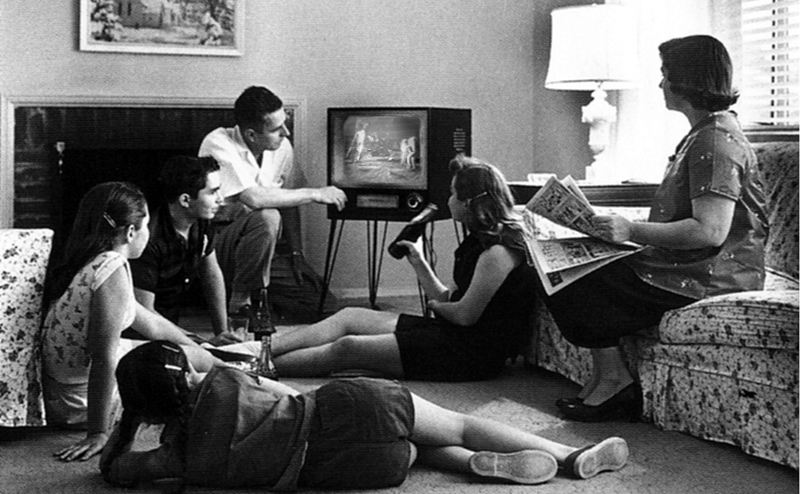

Millions tuned in to watch the iconic moments. But it was the ground station engineers that saw the raw footage arrive from the Moon.

These engineers – in California, Honeysuckle Creek and Parkes – saw clear, crisp video on special slow-scan television monitors. Regular TV viewers never got to experience that.

To get the signal onto their TV sets, it had to be converted. As a technical trade-off this process also downgraded the feeds’ quality.

Black and white image of family watching the moon landing on TV as it happened.

A global spectacle. Credit: Seeing Science

More recently, as part of an effort to showcase the best possible video from the Apollo 11 moonwalk, NASA enhanced the footage. They did this through a company that specialises in restoring old Hollywood movies. It then produced three official copies. One went to the US government archives, one went to NASA’s Johnson Space Centre in Houston, Texas, and the last was gifted to us. As a reminder of Australia’s critical role helping share the moonwalk around the world.

Back to the future

It’s Australia’s copy of these restored recordings that the National Film and Sound Archive of Australia now has in its collection.

The Apollo 11 Moon landing inspired humanity to dream and rethink what we are capable of achieving. In the same way, the missions of today and tomorrow will inspire future generations to push space exploration beyond what is imaginable now.

In our technologically-connected world, there’s no doubt all eyes will be skywards come our next venture to the Moon.

23rd July 2019 at 3:05 pm

The photo of the control room is back the front. The other people are (from right to left in your photo): John Bolton (Director of the Parkes Observatory), Jasper Wall (John’s PhD student) and four NASA engineers/technicians.

22nd July 2019 at 4:19 pm

The TV downlink has a separate S-band transmitter, because the telemetry (plus ranging & audio) already used all the 1MHz bandwidth on the primary transmitter. Or so I was told by the Honeysuckle veterans yesterday.