Over the last few years, hundreds of Victorians have found themselves with a mysterious affliction: a wound which just won’t heal.

It starts out as a harmless-looking spot. At first, it could be mistaken for an insect or a spider bite. Then it gradually morphs into a scab, a lump, and—most of the time—becomes a painful, swollen ulcer that gets bigger and bigger, and refuses to heal.

Treatment is possible, but it can be difficult. If left untreated, the ulcer can cause permanent scarring and damage.

Cases of the ulcer have increased significantly over the past few years. But no-one has definitively figured out know how it spreads, and how we can prevent it.

This is the mystery of Buruli ulcer.

Experimental Scientist Vicky Boyd is leading our lab work on Buruli ulcer.

Buruli ulcer, Bairnsdale ulcer, Daintree ulcer, flesh-eating bacteria … what is it?

Sometimes called the flesh-eating bacteria, Buruli ulcer is an infection of the skin and soft tissue. It’s caused by the Mycobacterium ulcerans bacterium, which is related to the bacteria species that cause leprosy and tuberculosis.

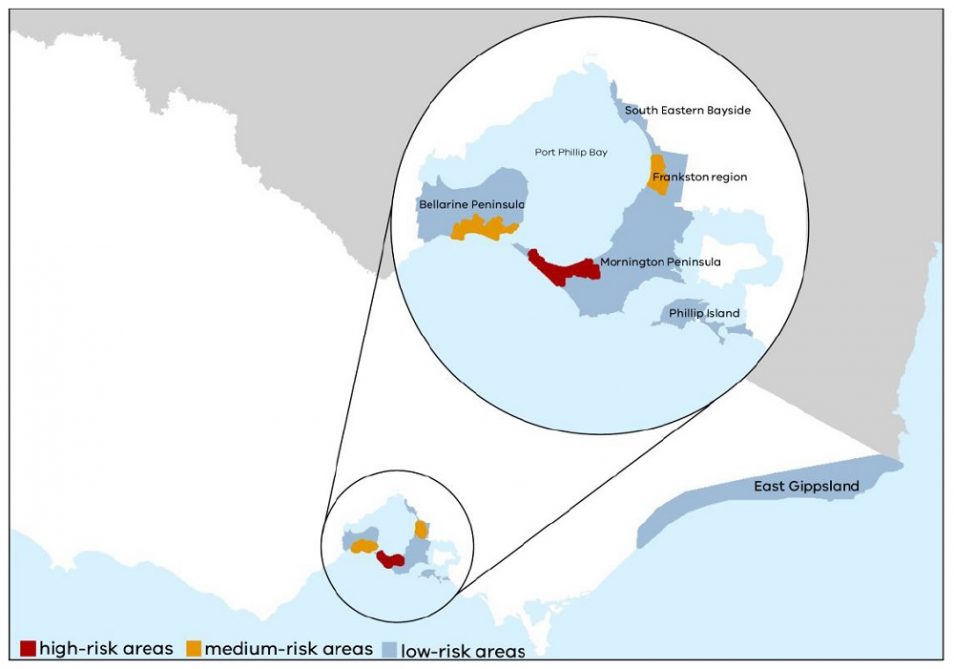

There are about 2000 cases of the ulcer reported worldwide every year—most cases come from tropical regions in Africa. Cases have been reported in Queensland, New South Wales, Western Australia and the Northern Territory over the years. But most Aussie cases have been in the temperate region of south-eastern Victoria, on the Mornington Peninsula, Bellarine Peninsula, South Eastern Bayside, Frankston, and surrounds.

Adding to the puzzle is the fact that Buruli cases in Australia have multiplied in recent years—there has been a 50% increase, year on year, since 2015. In 2017, 275 cases were reported, and last year the number of cases hit 340.

A doctor usually diagnoses Buruli based on where a person lives, their travel history, a physical examination, and swabs or a biopsy (examining a tissue sample). Treatment involves a course of special oral antibiotics, regular dressings, and occasionally surgery. Healing usually takes three to six months depending on how big the ulcer is—so early diagnosis and treatment is pretty important.

What do we know so far?

Scientists have worked on this puzzle for years. So far, we understand that people pick up the infection from the environment somehow, rather than picking it up from another person. But we don’t know exactly how the bacteria infects humans, or where the bacteria like to live in the environment.

It takes between two to nine months between exposure to the bacteria and the onset of symptoms (the average time is 4.5 months). It can also take a long time to get an accurate diagnosis. This delay makes it even harder to identify how a person may have picked up the bacteria in the first place.

Early research has shown that mozzies or other animals may be involved in spreading Buruli. But there may be other ways that the ulcer spreads—and this is the heart of the problem we’re trying to solve.

Areas in Victoria affected by Buruli ulcer. Credit: Department of Health and Human Services Victoria, Beating Buruli in Victoria

Solving the mystery to beat Buruli

We’re trying to better understand how Buruli ulcer is transmitted. And we want to find effective ways to prevent and reduce infections. We’re doing this through a joint partnership with Victoria’s Department of Health and Human Services. As well as the Doherty Institute, Barwon Health, Austin Health, Agribio, the University of Melbourne and Mornington Peninsula Shire.

Our infectious disease researchers are working with communities affected by the ulcer, to survey people who have, and haven’t, been infected.

Our researchers are also taking environmental samples including soil, water, insects and animal droppings from affected and non-affected areas, and analysing the samples at our Australian Centre for Disease Preparedness (formerly the Australian Animal Health Laboratory). This work is expected to wrap up by about early 2020.

We’re relying on the community to help us solve the Buruli puzzle. If you live in Victoria and were diagnosed with the disease after 10 June 2018, and you’d like to get involved in our study, please contact us via kim.blasdell@csiro.au. If you receive our questionnaire and haven’t had the infection, please fill it in as your answers are extremely valuable.

How to protect yourself from Buruli, in the meantime

While the rise of Buruli is a real concern, the overall risk of getting the infection is still low. Even in the areas where the infection is always around.

But if you are in the affected regions, it makes sense to protect yourself from potential sources. These include soil where the bacteria is naturally found. Also insect bites, and puncture injuries from thorns and plants. Try:

- Wearing gardening gloves and covering up arms and legs when gardening

- Using repellents and long clothing to stave off insect bites

- Treating and covering any cuts or abrasions

- Visiting your doctor if you have a skin lesion that won’t heal or is progressing quickly

- Mentioning the possibility of Buruli ulcer.

8th June 2020 at 10:35 am

This is also prevalent in West Africa,

If Cairo can extend their investigation here they can find answers too.

12th April 2019 at 10:40 am

I live in Kalimna West near Lakes Entrance. A couple of years ago I got the ulcer. As I don’t take antibiotics I tried something for myself and was very successful. My method was eyedropping 3% food grade hydrogen peroxide onto the ulcer which made it ‘gather its disgusting self into a grey-green disk the size of a fat $2 coin and over about 4 days it let go of the surrounding skin and I was able to brush it off with antiseptic cream. It left a hole that was not infected and my skin gradually healed back to normal. No scar, just slightly lighter skin. I do believe that hydrogen peroxide was widely used world wide before the ‘onslaught’ of antibiotics.

16th March 2021 at 2:10 am

Did the hydrogen peroxide sting the ulcer?

29th March 2019 at 8:00 am

It is a great shame that non of the clinicians that are treating the patients have opted for Maggot Debridement Therapy. I suspect this would resolve the ulcers very rapidly, resulting in less suffering and a better patient outcome, and save the patient a lot of money in the process. Maggot Debridement Therapy is a well established modality and should be considered in such cases.

11th February 2019 at 7:46 am

I’m sure I had one…not diagnosed as such. Start as a small itchy lump on my calf ,that I scratched. I assumed mossie bite. But straight away it was more like an ulcer. ( I have had bad ulcers before). Everyday I cleaned it out, betadined it and kept it covered. It ended up the size of a five cent piece and deep thru skin layers but not deep into tissue after 8 weeks , I went to doc and got antibiotics ..double dose..it finally closed up into skin layer and stopped producing pus. It took a few more weeks to heal completely. I thought I was extremely run down . I also was meticulous in cleaning it and I increased vitamin c thru berrocca and fresh juice, also I had oysters every week..zinc and selenium and fresh fruit and veggies.

You guys are aware that there are big Agricultural farms down here that grow veggies….continual tilling of soil (as well as many horse agistments). I wonder if they have changed their fertiliser practices

9th February 2019 at 11:39 am

Even if you find the cause it may be hardtop prevent just like preventing tooth decay that even with fluoridation, is still our most common disease where acid demineralisation exceeds remineralisation, mostly where food is trapped and brushing cannot reach. over 80% of cavities occur inside pit and fissure developmental faults in back teeth which dentists can prevent by placing costly sealants over chewing surfaces but only 12% of children aged 6-8 have at least one tooth with a sealant and personal sealants that relate to toothbrushing or before eating, may be the answer that the CSIRO should explore, and perhaps be part of STEM education in schools.