A sailor went to sea, sea, sea. To see what he could see, see, see. But all that he could see, see, see was… fishing gear.

That’s right, it turns out our oceans are littered with abandoned, lost or discarded fishing gear. Known as ‘ghost gear’, this debris significantly impacts our marine environment and wildlife.

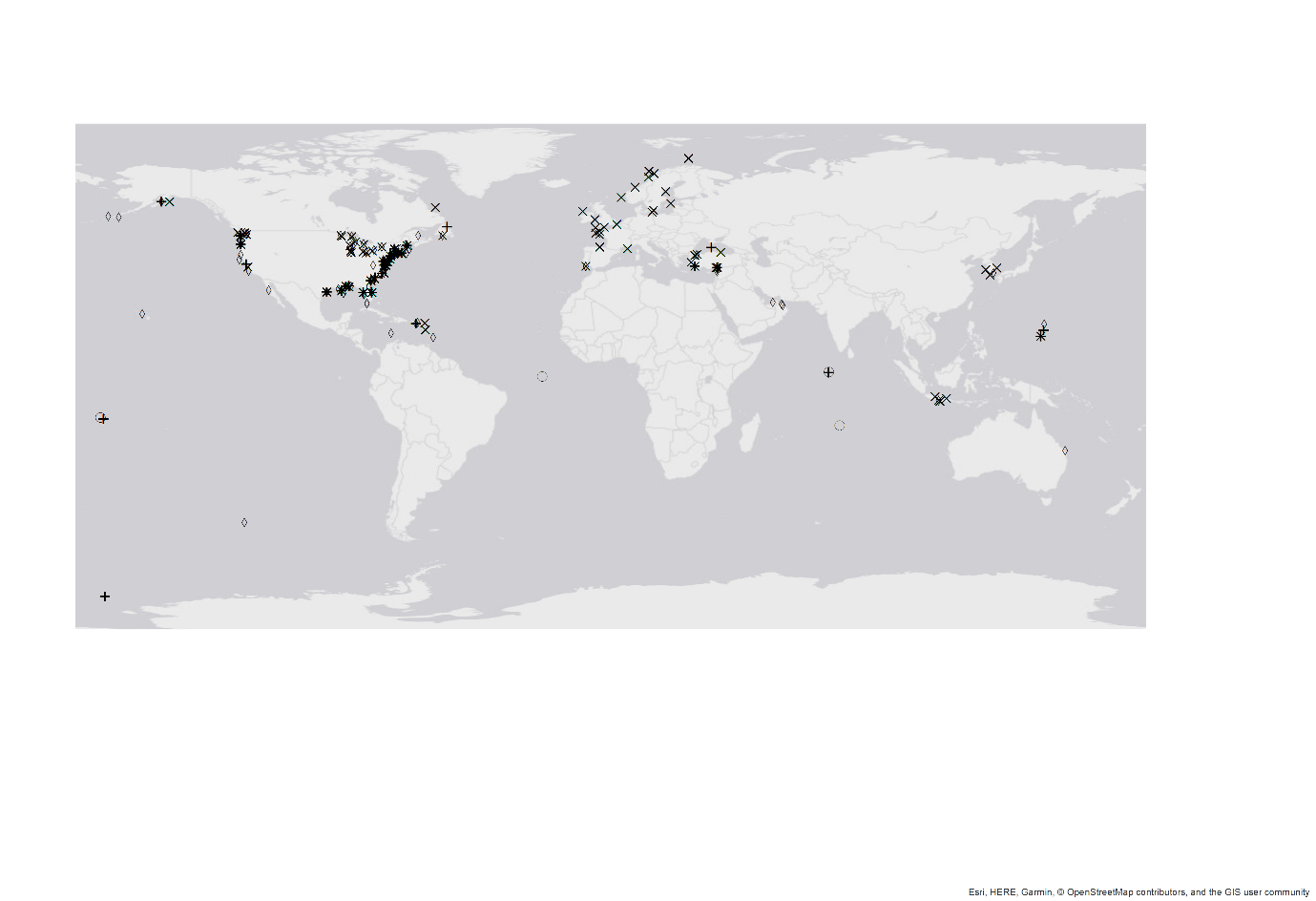

To help reduce marine pollution, we have generated the first ever global estimate of how much fishing gear ends up in our world’s oceans.

Marine sleuths: we have produced the first ever estimate of fishing gear lost in our world’s oceans. Credit: World Animal Protection Dean Sewell

Hook, line and sinker: what fishing gear is lost at sea?

To crunch the numbers for these estimates, we used data from all studies published between 1975 and 2017 (68 in total). We looked at the type of fishing gear used including nets, fishing line, and pots and traps.

Here’s what we found that is lost or discarded into our oceans each year:

- 6 per cent of all fishing nets

- 9 per cent of all traps

- 29 per cent of all lines.

And what influences fishing gear loss?

The most common reasons fishing gear is lost includes bad weather, gear becoming ensnared on the seafloor, and gear interfering with other equipment (known as gear conflict).

It’s estimated that over 40 million people are employed in fisheries globally so all that lost gear can quickly add up.

Caught up in it all

When fishing gear becomes marine pollution, it has significant consequences for marine life and habitats. It can take hundreds of years to breakdown.

Marine life can become entangled in it or think it’s food and eat it. The health of fragile ecosystems can be compromised. It can also be a navigation hazard for boats and ships, particularly if propellers get tangled in nets and lines.

Fishing gear that ends up in our oceans as marine pollution can impact marine life and ecosystems. Credit: NOAA

Studies on gear losses in Australian waters are few and far between. We were able to use one study that included estimates of gear loss in blue swimmer crab fishery.

Findings from this global study can be applied in the Australian context to support research priorities, risks assessments and monitoring.

Fishing for marine pollution solutions

Reports of commercial fishing gear lost at sea has increased over time. This is most likely due to improved reporting procedures, increased fishing effort and increases in the number of studies.

These new global estimates on fishing gear losses fill a critical knowledge gap. By understanding where and why gear is lost, we can help target interventions to reduce fishing gear ending up in our oceans, and better understand what data exists. This is good for industry, good for the environment, and good for global food security.

Currently, much of the data on gear loss is from the United States and Europe. This work highlights the need for more information about gear losses in the African, Asian, South American and Oceania regions.

We used data from 1975-2017 to determine how much fishing gear is lost at sea including nets, lines, pots and traps.

This study was published in Fish and Fisheries.

The researchers would like to acknowledge the late Joanna Toole from the Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations for her contribution and support for this research.

21st October 2019 at 9:07 am

Our property is on the Southern Ocean in S.E. S.A. On beach clean ups, we bag a lot of the debris you describe, as well as the paraphernalia of cray fishing such as polystyrene floats and plastic baskets. However, a fair bit of what we bag is clearly thrown overboard from the large container ships that move on the horizon between Adelaide and Melbourne, from items of personal hygiene to fluorescent light tubes. All that we clean from the shore must be a fraction of what is dumped, as it has to make it through rough seas and offshore reefs. International commercial interests are not interested in paying to dump their rubbish once they arrive at a port. In the interests of the marine environment, perhaps Australia should offer some incentive/cost alleviation to help solve this problem?

23rd September 2019 at 11:38 am

An excellent piece of work. I’m wondering if you can expand on the report to provide estimated volumes for the items listed (what does 6 percent of all fishing nets look like) and potentially affix a financial cost on the lost equipment (is any of it claimed through insurance)? I’d imagine that adding this additional information might help build more interest from within the industry.

Thanks again for a great article and investigation.

20th September 2019 at 4:23 pm

Thats a great piece of work. Well done.