Bringing together science and Indigenous and local knowledge, as well as supporting traditional practices that promote the survival of pollinators, forms an important part of the global response to pollinators under threat.

Lipotriches flavoviridis – a common native Australian bee. Image credit: flickr.com/jean_hort

UPDATE

The most thorough review of the state of the world’s pollinators has now reported and been reviewed in Nature. The landmark United Nations report on pollinator decline suggests policies that could be adopted by governments, including encouraging farmers to protect and manage wildlife that underpins crop production; mixing up monocultures to cut down on ‘green deserts’; and creating ‘bee highways’, providing habitat that links together to allow them to move across landscapes. This is what we reported in March when the work was underway.

What does a cappuccino and a zucchini have in common? The existence of both is reliant on industrious creatures called pollinators.

Pollinators help plants to grow fruit or seeds by transporting pollen from one part of a plant to another. Without this process, the plants could not reproduce, which makes pollinators vital to the production of many of the world’s most important crops, as well as millions of jobs and livelihoods that are dependent on this production.

More than three-quarters of the world’s food crops rely at least in part on pollination by insects and other animals and between US$235 billion and US$577 billion worth of annual global food production relies on direct contributions by pollinators.

Among the pollinators there are more than 20,000 species of wild bees alone, plus many species of butterflies, flies, moths, wasps, beetles, birds, bats and other animals.

But according to the first global assessment of pollinators, there is some cause for concern, with entire populations under pressure from things like habitat loss, diseases, pesticides, pollution, pathogens and climate change.

Last week, the The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)—which is for biodiversity what the Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) is for climate change—met in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia to discuss threats to pollinator species as part of the Thematic Assessment of Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production.

“Wild pollinators in certain regions, especially bees and butterflies, are being threatened by a variety of factors,” said IPBES Vice Chair Sir Robert Watson. “Their decline is primarily due to changes in land use, intensive agricultural practices and pesticide use, alien invasive species, diseases and pests, and climate change.”

“Without pollinators, many of us would no longer be able to enjoy coffee, chocolate and apples, among many other foods that are part of our daily lives,” said Simon Potts, the assessment co-chair and Professor of Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, University of Reading, UK.

Yolgnu Country, Arnhem Land. The Yolgnu people have totemic relationships that honour and protect stingless bees and their habitat. Image credit – Natasha Fijn

Indigenous and local knowledge helps provide a way forward

Chapter 5 of the assessment focuses on bringing Indigenous and local knowledge about pollinators together with scientific knowledge, while also investigating the broad socio-cultural values of pollinators and pollination.

“This is the first assessment from IPBES and the first global assessment of biodiversity to include information and recommendations on Indigenous and local knowledge,” said Dr Ro Hill, coordinating author of Chapter 5 and a researcher with our Biodiversity and Ecosystems Knowledge Systems program.

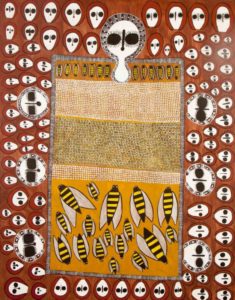

‘Wandjina and Waanungga’: Wandjina spirits keep country healthy for native bees and honey. Artworks like this one from the Kimberley region of Australia demonstrate the cultural importance of pollinators to Indigenous peoples.

© Sandra Mungulu / Licensed by Viscopy, 2015.

“The inclusion of Indigenous knowledge will be fundamental to the effective formulation of knowledge based policies for biodiversity into the future.”

Indigenous communities around the world understand local biodiversity in detail, and Dr Hill’s work provides examples from many locations where practices relevant to supporting pollinators and pollination are based on Indigenous and local knowledge.

“For example, the Yolgnu people in Arnhem Land, Australia, have totemic relationships that honour and protect stingless bees and their habitat,” she said.

The IPBES assessment found that bringing together science and Indigenous and local knowledge, as well as supporting traditional practices that promote the survival of pollinators, will form an important part of the global response to pollinators under threat.

The options identified by IPBES to help safeguard pollinators include:

- Maintaining or creating greater diversity of pollinator habitats in agricultural and urban landscapes;

- Supporting traditional practices that manage habitat patchiness, crop rotation, and coproduction between science and indigenous local knowledge;

- Education and exchange of knowledge among farmers, scientists, industry, communities, and the general public;

- Decreasing exposure of pollinators to pesticides by reducing their usage, seeking alternative forms of pest control, and adopting a range of specific application practices, including technologies to reduce pesticide drift; and

- Improving managed bee husbandry for pathogen control, coupled with better regulation of trade and use of commercial pollinators.

Find out more about our work relating to Indigenous knowledge and environmental management.

Pingback: Protecting the pollinators - and boosting farm production - ECOS

1st March 2016 at 5:20 pm

Knowledge transferred orally is notoriously vague and appears vulnerable to subjective interpretations through time – two tribes inhabiting same area may have differing accounts and understanding of the same phenomena, but possibly a good starting or reference point for possible avenues of objective investigation in the remaining few areas inhabited by keepers of indigenous lore.

1st March 2016 at 11:37 am

Wouldn’t it be great if councils and residents could tap into this knowledge to help select plants for footpaths, gardens, parks etc. Not only would it help the pollinators and crops, but the suburbs would actually take on a strong sense of place rather than than the usual rather uniform suburb look.

1st March 2016 at 8:30 pm

Suburban wild life reserves, local green space and home gardens and national parks and forest reserves are a very important means of preserving the endemic species of flora and fauna once common to any particular area in both the country and suburbia.Right throughout the world on both land and sea.