A picture of heliostats.

The Energy Centre heliostat array, taken from Tower 2.

The run of sunny weather we’ve had in south-eastern Australia over the last few weeks has been breaking quite a few records – and not just on the weather charts.

A team of solar thermal engineers and scientists at our Energy Centre in Newcastle have used the ample sunlight flooding their solar fields to create what’s called ‘supercritical’ steam – an ultra-hot, ultra-pressurised steam that’s used to drive the world’s most advanced power plant turbines – at the highest levels of temperature and pressure EVER recorded with solar power.

They used heat from the sun, reflected off a field of heliostats (or mirrors) and concentrated onto a central receiver point to create the steam at these supercritical levels. The achievement is being described in the same terms as breaking the sound barrier, so impressive are its possible implications for solar thermal technology.

So what is it exactly that these Chuck Yaegers of the solar world have gone and done?

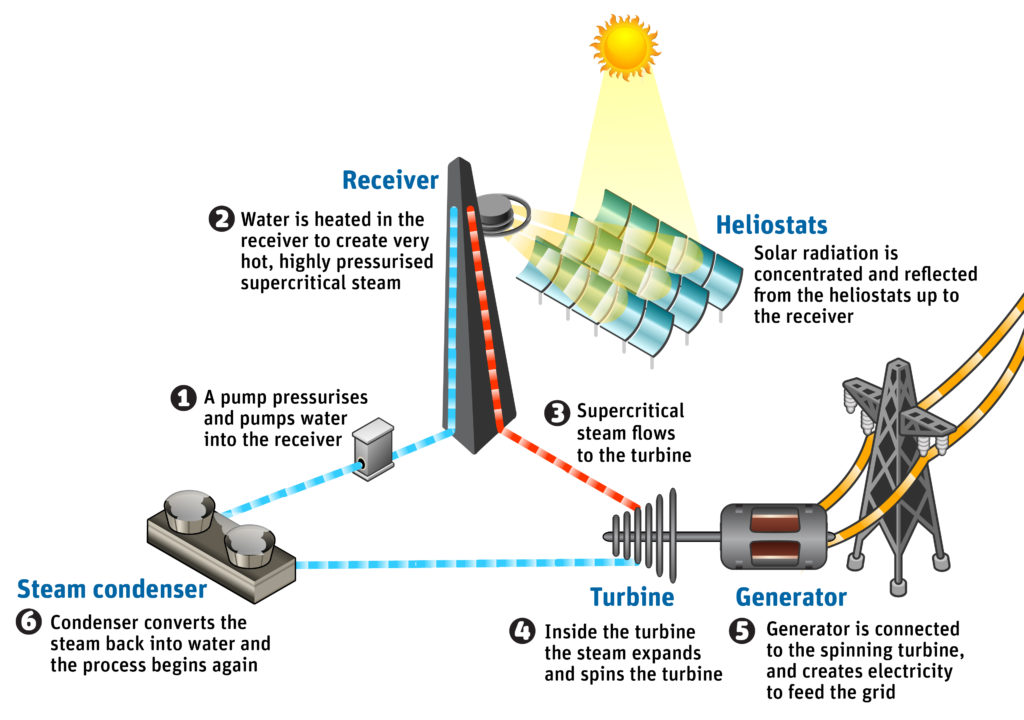

A graphic showing a solar thermal power plant works.

How a supercritical solar thermal power plant would work.

Put simply, the temperature of the steam they created (570° C) is about twice the maximum heat of your kitchen oven – or around the point where aluminium alloy would start melting. And the accompanying pressure (23.5 megapascals) is about 100 times as high as the pressure in your car tyres, or roughly what you’d experience if you were about 2 kilometres under the surface of the ocean.

That’s all impressive in itself. But when you take into consideration that this is the first time solar power has ever been used to create these ‘supercritical’ levels on this scale – traditionally only ever reached using the burning of fossil fuels – the real worth of this achievement begins to sink in.

Solar thermal, or concentrating solar power (CSP) power plants have traditionally only ever operated at ‘subcritical’ levels, meaning they could not match the efficiency or output of the world’s most state of the art fossil fuel power plants.

A picture of a solar thermal tower.

The solar thermal tower in action: check out the steam being generated.

Enter our team and their Advanced Solar Steam Receiver Project. To prove that solar thermal technology can match it with the best fossil fuel systems, they developed a fully automated control system which predicts the heat delivered from every mirror (or heliostat), allowing them to achieve maximum heat transfer, without overheating and fatiguing the receiver. With this amount of control, they were able to accurately recreate the temperature and pressures needed for supercritical success.

So instead of relying on burning coal to produce supercritical steam, this method demonstrates that the power plants of the future could be using the zero emission energy of the sun to reach peak efficiency levels – and at a cheaper price.

While the technology may be a fair way off commercial development, this achievement is a big step in paving the way for a low cost, low emission energy future.

The $5.68 million research program is supported by the Australian Renewable Energy Agency and is part of a broader collaboration with Abengoa Solar, the largest supplier of solar thermal electricity in the world.

For media inquiries, contact Simon Hunter – Phone: +61 3 9545 8412 Email: simon.hunter<at>csiro.au

21st June 2016 at 3:42 pm

Is there a risk to aircraft when the mirrors are moving?

16th December 2014 at 11:43 pm

I’m sorry, but this is a reality check.

Inasmuch as this technology is desireable, it is not economically viable.

All that apparatus produces about 20 horsepower.

Do the math.

17th June 2014 at 7:53 pm

Its an awesome technology and congratulation to CSIRO