We’re bringing together Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western Science. Credit: Jo Myers/CSIRO

Go west. Life is peaceful there. Go west. That’s what we did, to one of Australia’s greatest natural wonders – the Kimberley.

The region encompasses more than three million hectares, offers a plethora of biodiversity and brings together four marine parks. It’s highly valued for its natural beauty, flora and fauna, cultural values, tourism and fisheries. And has been a place of importance for Indigenous Australians for thousands of years.

The Kimberley’s remoteness makes undertaking science there challenging. But its uniqueness and complex ecosystems make it a scientific hot spot. We’re bringing together Traditional Ecological Knowledge with Western science to enrich understanding of the region…in particular about life under the ocean surface.

Our research has been part of the Western Australian Marine Science Institution’s (WAMSI) Kimberley Marine Research Program. WAMSI has brought scientists together to assess threats in the region and collect scientific data to support future management decisions.

Integrating science and culture in the Kimberley

Our research in the Kimberley would not be possible without the knowledge, cooperation and trust from Indigenous rangers, traditional owners and research partners.

Perfect match: Traditional knowledge and Western science has enhanced our understanding of the Kimberley region. Credit: Jo Myers/CSIRO

We worked with the Bardi Jawi Rangers who welcomed our partnership and recognised the importance of integrating scientific and cultural knowledge to benefit ongoing management of the Kimberley.

Kevin George, a Bardi Jawi Indigenous Ranger said “there’s important animals and species that are living in the marine world and have been a big part of our world for years.”

“Some of the questions we’ve envisaged have been answered by CSIRO and the researchers that have been working with us. And the rangers have learnt more from the scientific world.”

Making tracks: DNA traces reveal marine life movements

As organisms move in the ocean, they carry a record of their origins in their unique DNA fingerprints. We used this DNA to find out how far marine life moves in the area and interacts with the geography. This is the first time ever that scientists have achieved this.

Samples were collected from seven species at 157 sites across the Kimberley with the help of research institutions, traditional owners and indigenous rangers. We were then able to analyse the samples for their genetic fingerprints.

We found that corals and seagrass tended to travel tens of kilometres or less. In contrast, the two fish species and the mollusc (sea snail) we investigated travelled much further – up to hundreds of kilometres. Ocean currents can influence this.

Look out, DNA in the water! We are using genetics to understand the movements of marine life in the Kimberly. © Kathryn McMahon, Edith Cowan University

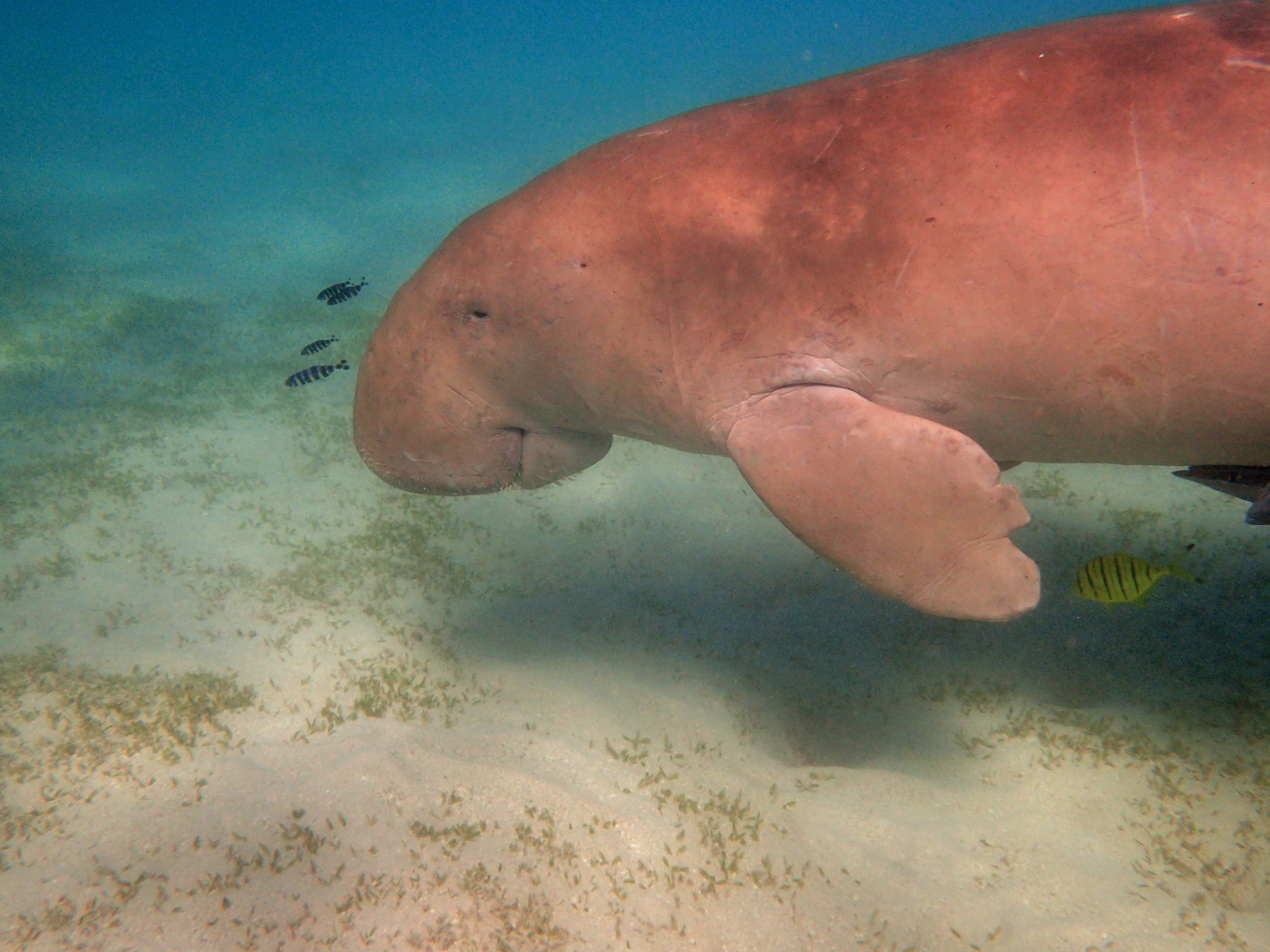

Cows of the sea moovements

The largest population of dugongs in the world are found in the Kimberley and Pilbara regions. They have high cultural value to Indigenous coastal communities.

We know dugongs can get big – up to 400 kilograms – but there has been limited information on their numbers and location. However, we now have the first baseline study of how many there are and where. This includes identifying critical habitats, environmental factors and pressures, and effective measuring and monitoring tools.

This research provides substantial data for dugong monitoring by Indigenous rangers and helps to assist with conservation of the species.

The world’s largest dugong population inhabits the Kimberly and Pibara regions. And it’s no wonder with the area rich in it’s favourite food, seagrass.

Take a closer look: microbial communities

We researched the microscopic plants and animals that reside in the water column, as well as those that live on the seafloor. This was to gain a better understanding of the marine food chain. And how changes to microscopic species can influence the productivity of others.

Any changes to ocean conditions from climate and land use will impact the smallest of species in the food chain. From plankton through to small invertebrates such as crabs and snails, and larger species like whales.

So like humans need nutrients for good health, so too do our oceans. They are the backbone for the marine food chain. And the impact of changes could flow up from seagrass meadows to top predators.

Let there be light: life on the seabed

Water turbidity (or water clarity) influences the amount of light in the water. This can impact how quickly and plentifully aquatic plants grow, especially on the seabed. This is particularly important for the marine animals that rely on the aquatic plants for food.

Satellite images are improving our knowledge on water turbidity and how changes can impact aquatic plants on the seabed.

We used satellite data and remote sensing to accurately measure water turbidity in the Kimberley and how it changes. This helps to identify vulnerability of plants living on the seabed.

We found that high tide means high turbid conditions. The turbidity was greatest during the winter months. This suggests that winter heat loss and increased wind stress during this time of year enhances the tidal effect.

Working with Curtin University and the Western Australian Department of Parks and Wildlife, our method was specifically designed for the Kimberley. It is built on 16 years of archived satellite data, to provide daily average maps. This has provided insights into natural variability and highlights changes to help with management of the marine ecosystem.

The research conducted in the Kimberley has informed our science and demonstrated the importance of integrating current science with deep Indigenous knowledge. We now can scientifically describe where marine life is, where they are going, and how to help manage marine reserves and fishing zones in the region. It’s also helping to understand future changes to ensure effective management of the coast and marine parks.

2nd August 2019 at 6:58 am

Loved the news on Kimberley marine research with Aboriginal perspectives.