You might think that solar panels would work best in summer, when there’s more sunshine. But how hot is too hot for effective solar generation?

We have plenty of sunshine in Australia, and in summer, we have extra daylight hours and even higher solar exposure. So, what does this mean for the production of solar energy?

Renewables are playing an increasingly important part in our energy mix. So, how do seasonal variations affect our ability to generate solar when we need it most?

How do solar panels work?

Solar photovoltaic (PV) panels adorn over two million household rooftops across Australia. This is one of the highest levels of solar uptake in the world. Australia always punches above our weight on the world stage, if it’s not cricket or surfing it now includes renewable energy – Go Australia!

Solar panels capture sunlight. How? First, light energy from the sun strikes the surface of the active material that makes up the solar cells (typically a semiconductor made from silicon). This excites electrons in the material, which we then capture as electricity.

You might think solar panels would work best in summer, when there’s more sunshine. But how hot is too hot for effective solar generation? Are long, cloudless days in autumn or winter the true friends of solar PV?

We asked our solar technologies expert, Professor Gregory Wilson and his research team in Newcastle to investigate.

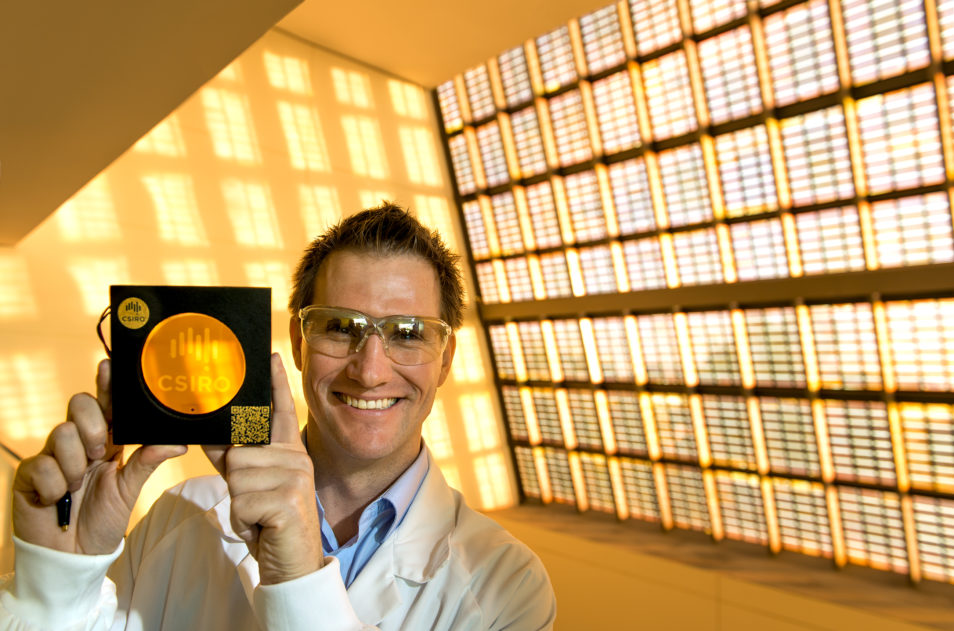

Gregory Wilson is the lead of CSIRO’s Solar Technologies group.

Is summer or winter better for solar?

“Our Newcastle site has more than 300 kW of installed solar panels and quite possibly the most accurate solar ground station in Australia,” Gregory told us. “We took a close look at data from the few days around the winter and summer solstices (the peaks of each season). From that we can understand the effects of a ‘typical’ summer and winter day on how much solar energy we can capture.”

We noticed that the amount of solar energy (solar irradiance) on a clear day in summer is about double the sunlight we receive in winter.

Despite the fact temperatures outdoors are higher in summer (sometimes over 40 °C), the amount of light converted to electrical energy is still far higher in summer than in winter. In fact, the electrical energy output on a very cloudy summer’s day, is still higher than a clear, sunny day in winter.

“Simply put, summer generates a lot more electrical energy,” Gregory said. “There are many factors that affect the amount energy generated by solar PV. In summer these factors come together with more daylight hours, generally sunnier days, and even daylight savings creating a shift in energy usage.”

If you’re energetic about energy, you can check out the graphs showing this research.

Solar panels on the roof of our Newcastle office. In the background you can see the heliostat fields for our concentrated solar thermal research.

Good afternoon, sunshine

If you visit our Energy Centre in Newcastle, you’ll see west-facing solar panels on the main building, to maximise the solar energy captured in the afternoon. Why do we do this?

“This approach to energy generation is a practical example of ‘peak-shift’,” Gregory said.

“It’s where we orientate the building and solar array so the peak time of solar energy collection is shifted from, say, a midday maximum to a mid-afternoon maximum. So, we collect energy late into the afternoon, as the sun sets in the west, to match most people’s larger energy needs in the afternoon and night time.”

“The array continues to generate electricity late in the afternoon, after 7pm around the summer solstice. But it’s clear that more energy is still captured in summer than in winter.” (See peak shift graph).

The façade of the Newcastle Energy Centre is a PV array featuring 22 kW of thin-film solar panels. It faces west to capture the afternoon sun.

Reaching new heats: solar in summer

While sunny warm days seem to be best for solar energy generation, silicon PV panels can become slightly less efficient as their temperature rises. Some silicon PV solar panels produce less energy when really hot. On the other hand, thin-film PV panels can generate slightly more energy on hot summer days.

So how do we avoid the solar panels overheating? Some suggest we float the solar arrays on dams and large bodies of water to keep them cool. We might also want to engineer new ways of cooling the panels with smart coatings that reflect the sun’s thermal energy or using new thin-film semiconductors (like our perovskites). Another idea is to put the thermal energy to good use and combine solar PV and solar thermal to create a ‘photovoltaic-thermal’ (PVT) panel that generates electricity and hot water. The ways we can innovate to make renewable energy work for us are only limited by our imagination!

Other bright ideas: better solar panels

It’s not just well-placed panels. Our scientists are working on next generation solar technologies, finding ways to capture even more energy from the sun.

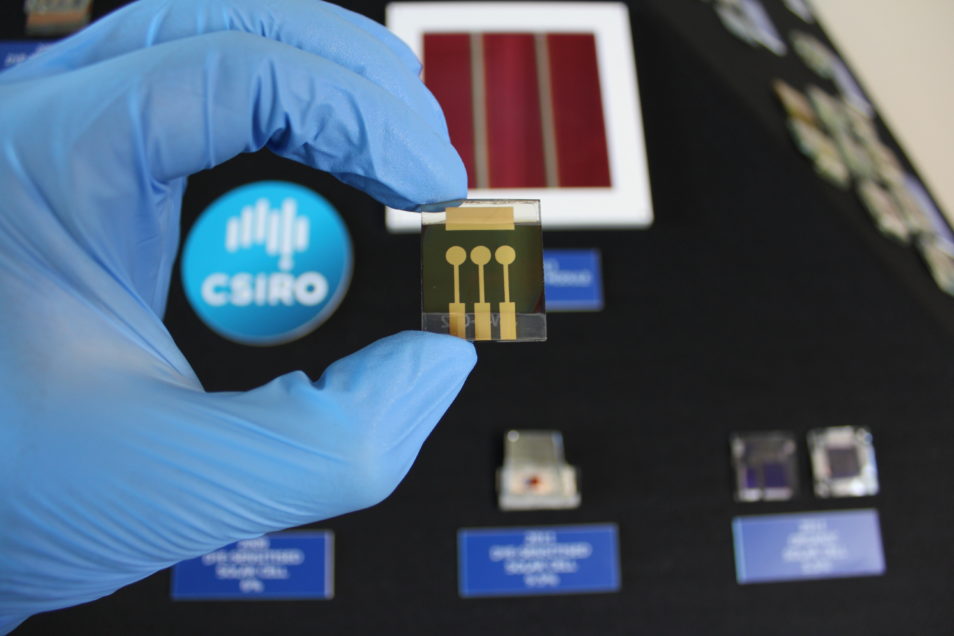

We’re testing solar cell panels and systems, and we’re looking into new high-efficiency, low-cost solar cells. One example using a new material based on perovskite semiconductors. This technology combines the light-capturing potential of perovskites with silicon into a ‘tandem solar cell’. It would increase overall absorption of energy from the sun, improving the solar cell performance and energy efficiency.

Perovskite semiconductors are a new type of thin-film solar cell technology that has the potential of increasing the performance and energy efficiency of solar panels for electricity generation.

This is good news for solar technology in Australia where we have the highest average solar irradiation per square meter of any continent globally, no matter what the season. We can capture our famous sunshine and use it on a journey toward a more sustainable energy future.

And with a warming climate, it’s vital that we incorporate several clean energy technologies into the mix. Solar will do its fair share, but we also need to think about what else we can use. For example, using the sun’s thermal energy to create electricity or industrial heat, or even solar fuels using concentrated solar thermal technologies. Then, we have to link them all together through networks and intelligent management systems like a virtual power plant.

31st July 2022 at 3:12 pm

I am being advised by my solar provider/installerthat the solar panel layout at my home can achieve an acceptable efficiency on frames at an angle of 10-12 degrees facing north. This seems to contradict the information I glean from the internet. My premises are on the east coast of NSW four hours south of Sydney which would indicate that the correct angle should be 35.0 degrees to the horizontal. Could you please comment.

3rd August 2022 at 4:35 pm

Hi Jim, I can appreciate the confusion here.

It might be worth going back to your installer and seeking a bit further clarification as the wording they have used may be the most important part to understand the information they have provided.

As an example you state ‘…can achieve an acceptable efficiency…’ which may be correct depending on your actual installation.

For instance, if you have a roofline with a low angle or a skillion roof, then a frame tilt angle that matches your roofline might provide the most affordable option and an acceptable efficiency. This could be in an effort to keep installation costs down, by reducing the amount of framing materials, they have suggested this type of angle/frame to install.

You are on the right track with your information you have looked into regarding preferred installation orientation. For an installation location in Australia, a north facing array would be the most effective. In addition, an ideal tilt angle would be one that orientates the flat surface of the panel to be normal (an angle of 90 degrees) to the position of the sun, so the incident light is ‘direct normal’ to the panel. This is typically estimated to be the latitude of the installation, in your instance/location this sounds like you are located at a latitude equivalent to 35 degrees.

Now, if you consider what the pitch of your roofline is, and in Australia this is between 15 degrees to 22.5 degrees, then a frame at 10-12 degrees would bring you close to that preferred tilt angle. In many instances the costs outweigh the benefits for payback on the additional cost for a frame that places it ideally at ’35 degrees’ so an economic compromise is to install the solar panels directly on the roof, which would then have the array tilt angle at 15 degrees or 22.5 degrees. Does this affect the overall annual energy yield? Yes, however there is only a marginal difference at this roofline tilt angle and the energy difference (as a cost of electrical supply from the grid for a net increased demand or export tariff for net export) would not be enough of a financial incentive to spend more money on the frame at installation. Hence, an acceptable efficiency.

So my advice is to contact your installer and have a conversation with them about what specifically they meant by the installation angle of the system and why this is an acceptable efficiency and I am certain you’ll feel much more informed and comfortable to make the decision you need.

24th May 2022 at 9:58 pm

Thanks for sharing such informative and useful content with us keep sharing.

Solar companies in Melbourne