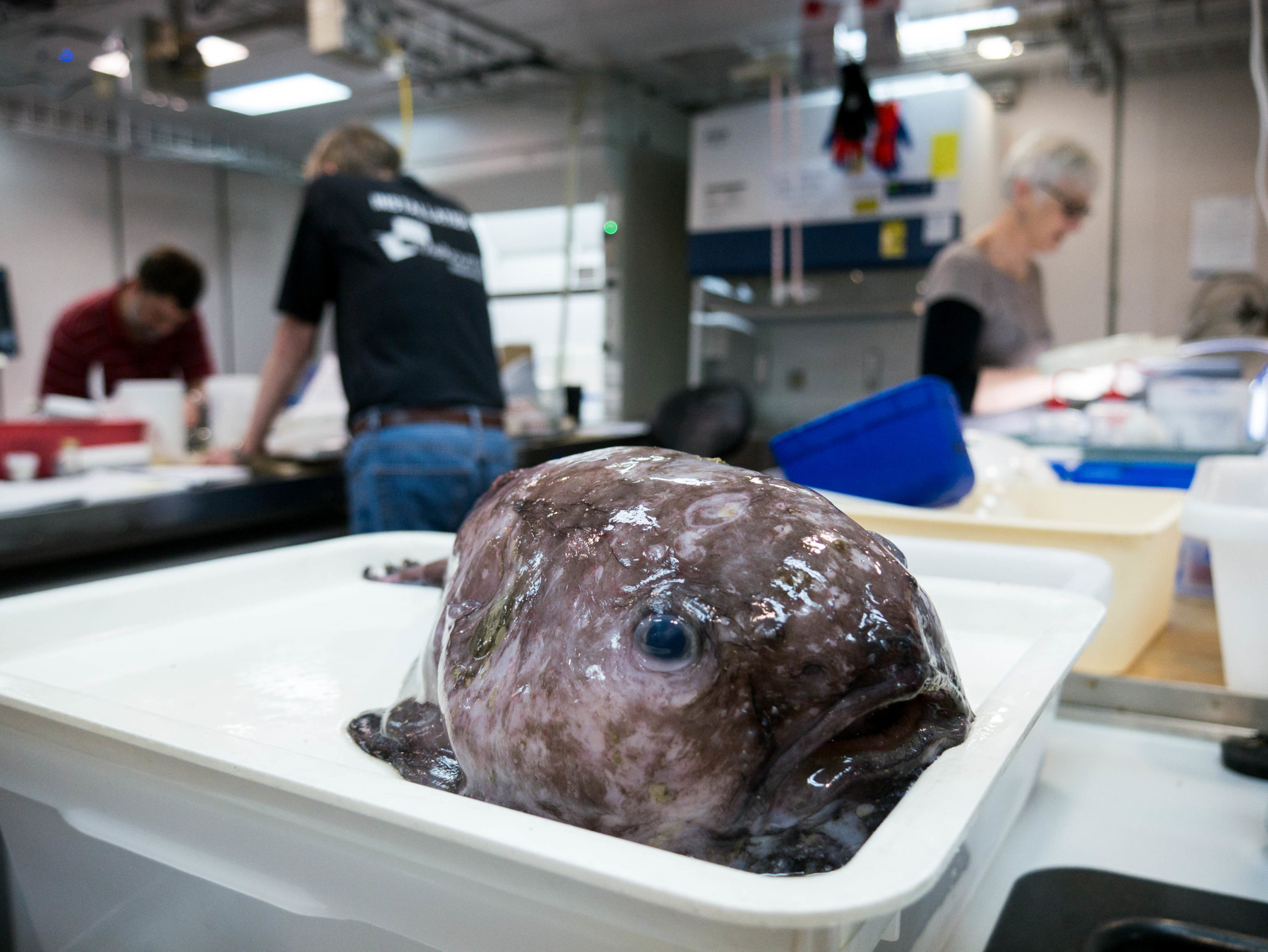

My cousin was voted World’s Ugliest Fish in 2013! This blob fish was collected from a depth of 2.5km off New South Wales. Image Asher Flatt/Marine National Facility.

How do you name a fish from the abyss, especially if that fish is faceless? That’s the question that a team of Australian scientists have gathered at the Australian National Fish Collection in Hobart to answer.

Last year, an international team of 40 scientists were led by Museums Victoria on a world first survey to explore marine biodiversity in the abyssal waters off the east coast of Australia. Called Sampling the Abyss, the voyage aimed to increase our understanding of one of the most inaccessible and unexplored environments on the planet.

Understanding which fish species occur where, and identifying new fish species, is the starting point to managing marine biodiversity. The voyage made both unusual and important discoveries.

A faceless fish from the abyss. Image: Asher Flatt

A faceless fish from the abyss. Image: Asher Flatt

Top of the list was the rediscovery of the faceless fish, a deep sea fish with no visible eyes and a mouth on the underside of its head. This species led the charge of bizarre creatures that rose from the dark, crushing depths of the abyss.

Other mysterious creatures discovered in the deep included at least three new Australian records of gelatinous cusk eels; blob fishes, cousins of Mr Blobby who was voted the World’s Ugliest Fish in 2013; bioluminescent cookie-cutter sharks; a haul of frightening lizard fish; and graceful tripod fish, which prop on the sea floor on their long fins waiting for food to drift within reach.

The abyss is the largest and deepest habitat on the planet, covering half the world’s oceans and one third of Australia’s territory, but is the least explored area on Earth.

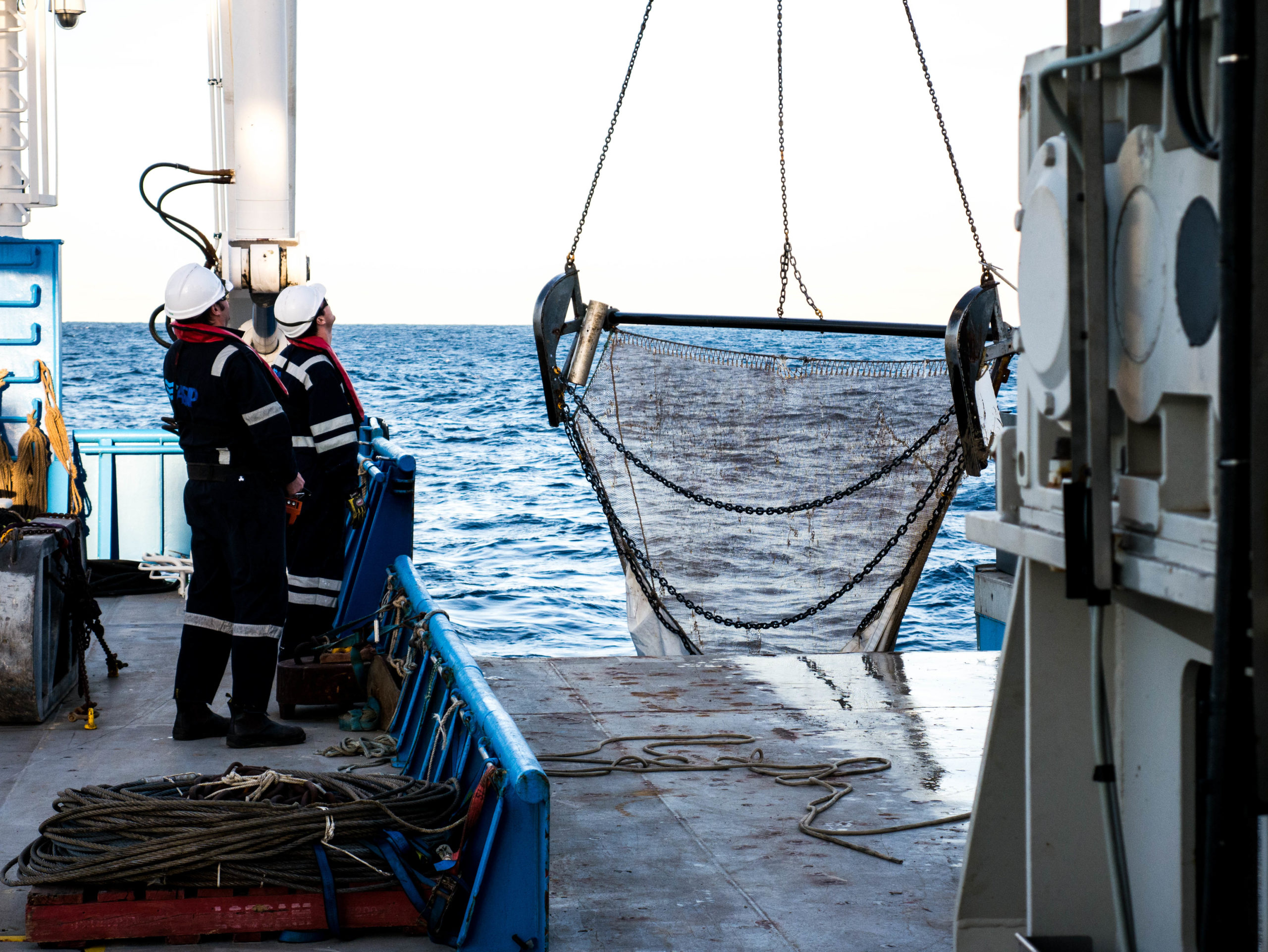

Aboard RV Investigator, researchers used a beam trawl and other equipment to collect these fishes from depths down to nearly 5km, which is a new capability for an Australian research vessel. In this line of work, scientists play the long game – it can take up to three hours or more to lower equipment to such depths! After an hour on the sea floor, the catch is hauled up and onto the deck, sorted and taken to labs on board Investigator for processing.

Scientists then spend many more hours processing the catch on board, separating different species, photographing specimens to record their colours, extracting muscle samples for DNA analysis, preserving specimens in formalin then ethanol, and freezing some of the catch for later processing.

And this is just the beginning of the journey for many of the specimens.

At our Australian National Fish Collection this week, scientists from CSIRO and Museums Victoria are using a mix of morphological (what it looks like) and molecular (what it’s made up of) approaches to identify the species of fishes collected. This careful and thorough examination is vital because deep water species are typically poorly known to science.

In all, scientists have now identified over 100 different fish species from the voyage, and possibly some that are new to science.

The task of identifying these fishes is a truly international effort, with specimens already being sent to scientists in Denmark who specialise in abyssal fishes. They will compare specimens from different ocean basins to determine if the fishes collected during the voyage are new species.

This frontier science to the edges of our known world is vital for improving our understanding and management of the deep sea environment.

Female scientist standing in rows of jars on shelves and examining jar.

The Australian National Fish Collection is an important natural history collection both nationally and internationally.

Specimens from the voyage have been shared between five Australian collections (Museums Victoria, Australian Museum, Queensland Museum, Tasmanian Museum & Art Gallery and CSIRO Australian National Fish Collection), and are available to the international research community for study. It is anticipated that new discoveries will continue to be made from collected samples for decades.

11th October 2018 at 2:55 pm

I did some lab work for the Antarctic Division in Kingston Tasmania as a Marine Biologist. I studied these creatures and identified the contents of their stomachs and otoliths (fish ear bones). Antarctic Division is a great place to work……

8th March 2018 at 11:08 am

Wow! What fascinating but scary looking creatures. You’ve got to wonder what else there is down at those depths.

Are you going to publish a photo books of the other specimens that were collected? I’d like to see more of these exciting discoveries. When articles are published with the outcomes of the research work in available can you please give an update and include links to publications please?

Thank you ladies and gentlemen for all your research and hard work.

8th March 2018 at 11:05 am

Simply incredible research. People do tend to treat our oceans as the place for dumping all sorts of waste. Out of sight, out of mind. This research will provide evidence of these effects.