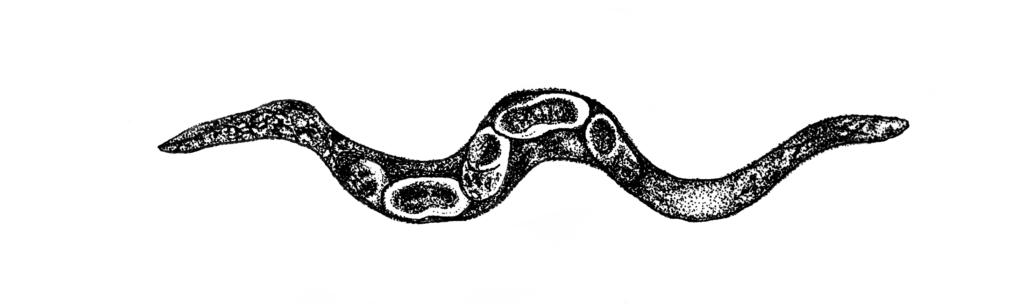

Haycocknema perxplexum, the cause of a curious disease investigated over the past two decades by Dave Spratt of our Australian National Wildlife Collection. Illustration by Natasha Mansfield, CSIRO.

At different times in the 1990s, a botanist and a firefighter went to hospital with a set of generic symptoms including a feeling of discomfort, muscle pain, general illness and unease. After medical examination, they were found to have polymyositis—a chronic inflammation of the muscles—and wasting away of muscle density.

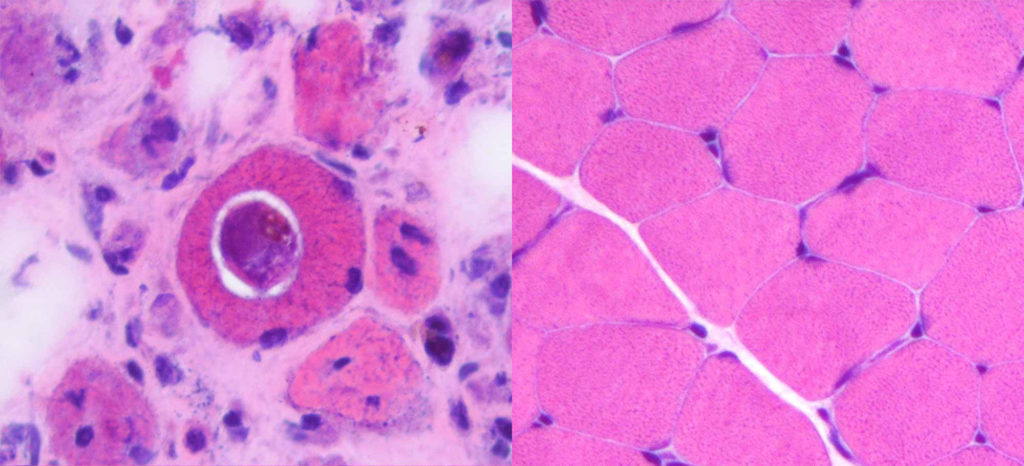

In both cases, biopsies of the wasting muscles revealed something growing and reproducing inside the muscle tissue. Despite an initial misdiagnosis of one of the cases, both patients were eventually understood to have had infections of a previously unidentified microscopic nematode (also known as a roundworm).

(Left) A section of muscle cells under a microscope showing an infecting H. perplexum parasite—the round structure with the white halo inside the larger mid-pink structure of the muscle cell. The patient has significant muscle deterioration—most of the dark blue/purple spots are muscle cell nuclei and in a healthy muscle (right), would have a full, muscle cells around them. Image adapted from: Dr Thomas Robertson, with permission.

The parasite was described in 1999 by Dave Spratt and colleagues as Haycocknema perplexum—the species name alluding to the mysterious nature of the nematode, its unknown origin, and some unusual physical features of the female. To date, only a handful of further cases of infection have been reported, and only in North Queensland and Tasmania.

There is currently little to no understanding on how any of the patients were infected.

Symptoms after infection appear gradually over several years. Diagnosing an infection has so far relied on a pathologist spotting the nematodes when looking at muscle biopsies under a microscope. Last year, however, a group of scientists, including Dave Spratt, published a newly-developed DNA-based test that will help to identify suspected human cases in the future.

There is currently little to no understanding on how any of the patients were infected.

The nematode is tiny. The female is only about 0.4 millimetres long and the male is about 0.3 millimetres. We don’t know very much about its life cycle yet, but we do know that H. perplexum reproduces by ‘matricidal hatching’. This is where the eggs develop into larvae, hatch inside the female and burst from her head to infect additional muscle cells. Talk about a mother’s love!

If you do end up becoming infected (rare as that would be), there is a broad-spectrum drug called albendazole that appears to be effective in wiping out the infection. And while being treated with sheep drench sounds a bit unpleasant, if the infection is left untreated, the muscle wastage will lead to breathing difficulties and eventual death.

This article was published with permission, Australian Academy of Science. Read the original article.

13th January 2018 at 11:23 am

I am in awe of the Human organism as a fortress constantly fighting off attack.

Of the Human brain that evolved to enable scientific understanding and methods for that organism to protect its host using chemical warfare. Or the possibility there were two separate organisms historically balanced within a human host that have been put on a path to self destruction by the development of the large human brain.Or is this human brain simply in need of more medication?

10th January 2018 at 11:53 pm

Sound frighteningly similar to Toxoplasma Gondii (well sort of) but sounds a little more similar to Sarcosporidia (or Sarcosporidiosis which ever you prefer to call it)…

9th January 2018 at 3:20 pm

Good old Albendazole to the rescue again. Helps in cases of Gardia to.