Does your bread get the green light when it comes to the environment?

Simple question: how green is your bread? No, we’re not asking how mouldy it is (that’s another story). We’re talking about the environmental friendliness of a simple loaf of white bread, and it’s an important question to ask, with around three-quarters of Australian shoppers buying bread each week. The answer can be pretty tricky, and you have a vital part to play in the final result.

Adding it all up

Using a method known as a life cycle assessment, we can calculate the environmental impacts that occur throughout the bread’s existence.

To begin with, there are land use considerations from the biodiversity impact on native flora and fauna. Then there’s water use, and thankfully Australian rain-fed wheat crops use minimal additional water. But that isn’t the case for irrigated crops like sugarcane for the sugar that’s added to your jam (we’ll get back to that later).

Australia’s dryland farmers are among the world’s best, and are making carbon efficiency improvements of about 1 per cent each year. But on the farm, nitrogen fertilisers are still one of the biggest factors for carbon emissions and the wheat seed needs to be planted and then harvested –all using machinery that uses diesel.

By the time enough wheat to make a loaf of bread leaves the farm, it’ll have generated, on average, around 200g of greenhouse gases per kg of wheat.

A tractor and header harvesting wheat.

A fine wheat crop. Image by John Coppi

Add one part flour, two parts energy, and stir

After the wheat is taken to a mill to be ground down to flour, it’s transported to a bakery. At this stage the wheat for our bread will meet other ingredients such as yeast, canola oil and vinegar, which have all made similar production journeys.

These steps of milling and baking require significant amounts of electricity. In a country like Australia, where we have a predominantly coal-based power grid, our electricity has a high emissions footprint. As a result, a kg of flour has about 270g of “embedded” greenhouse gas emissions, including those of the wheat growing.

Bonus factors to consider: what about the bread’s packaging – is it paper or plastic? It then needs to be transported to the store, where electricity keeps the lights on and check-outs operating.

Time to add your contribution to this

Allow us to propose a toast…

Got a hankering for bread? It’s time to go to the shops! But will you walk, catch public transport, or drive yourself? Also, will you nip down to the shops just for the bread loaf; or will you go for your one big weekly shop? The latter will spread the environmental impact across multiple grocery items.

Back at home, if you toast your bread – versus eating it fresh – you’re using around 1000 watts of electricity, which is about 12kg of CO2 yearly if you eat toast for breakfast every morning, or about 30g of CO2 for two slices of toast.

Adding a spread on your bread also impacts on your bread’s carbon emissions. Remember the sugarcane we mentioned earlier? Having a jam or preserve with added sugar will increase the impact compared to other spreads. Oh, and do you like to butter your bread? That’ll be around an extra 125g of CO2 per slice (15 grams of butter).

Ultimately a loaf of supermarket bread can cost your hip pocket anywhere from $1 to $8, and the total environmental cost across the entire life cycle (from farm to tummy) may vary by about as much. But if we crunch the numbers, a reasonable assumption is around 550g of CO2 per loaf, or some 25g per slice, before you’ve even touched it. So don’t overdo it on the butter!

This story is going off

But it turns out the worst thing you can do after buying a loaf of bread is… nothing.

Just think about all the time, effort and resources that went into making that tasty, fibrey goodness. After adding up all those factors from the farm to your pantry, the worst thing you can do is let any food go to waste and throw it out.

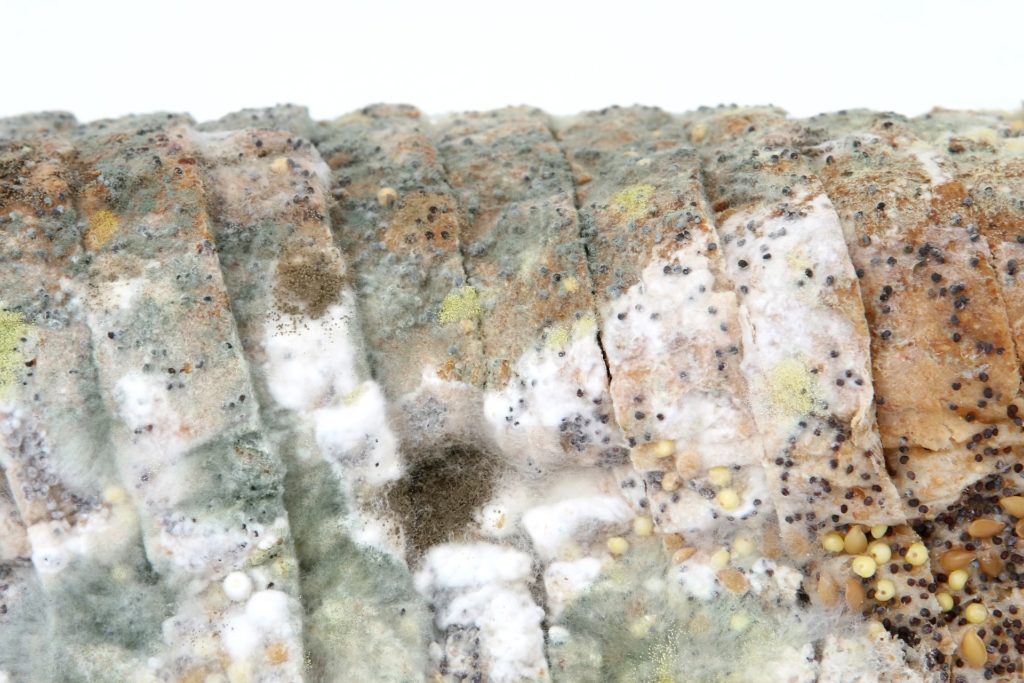

So the first step to making sure your loaf of bread has a big environmentally friendly green tick? Don’t let it turn green and mouldy.

Counting the cost

Life cycle assessments track the environmental impact of agricultural products.

4th May 2018 at 10:37 am

We bake most of our own Wholemeal/Multi-Grain Bread at home – we do not use a “Breadmaker”. Its all done by hand. None of it gets wasted or thrown out. No new loaf is started until the old one is finished Even if its just the final crust that gets eaten first.

We would love to be able to buy CSIRO’s “Barleymax” Barley, we’d pop it in a blender to make a very coarse flour!It would be more convenient if we could buy it ground!

Just what is it the commercial bakeries are putting in the bread they sell? When you see a, usually plastic-packed, loaf with a stamp telling you the “Use By” or “Best Before” date is three weeks away, surely we must ask ourselves what chemicals are they using.

It may take longer but making bread – and No, it doesn’t have to be airy-fairy so-called “Artisan Bread” – is a lot of Fun – sometimes it comes out almost perfect other times it looks like it’s had a fright!

4th May 2018 at 9:53 am

Given the high environmental cost of medical treatment and all that entails, an obesity epidemic underpinned by excess consumption of high carb and sugary foods, and indications that starchy food residues are the main cause of periodontal disease, allowing the bread to go mouldy (or leaving it on the shelf) could actually be the best outcome for the environment.

1st May 2018 at 2:10 pm

One of the problems with composting food is that the compost heap or bin attracts rats. Keep an eye out for these pests, they can cause heaps of damage if they get into your house.

27th April 2018 at 7:01 pm

Here in the UK our problems with bread are overcome by the purchase of untreated organic flour, organic yeast and fermenting with yeast for long periods, overnight at the least, to reduce the impact of lectins. Here, I learned about the problems lectins cause by creating leaky gut syndrome by reading; The Plant paradox by Stephen Gundry MD. Another book to read is The Iodine Crisis by Lynne Farrow, one part of which poses questions regarding the decision to remove Potassium Iodate from bread flour and replace it with chemicals that seem to have increased, for example, cancer three fold. Then, just to round this message off, particularly as the starting point was caused in Australia, everyone with a mind to solve problems caused by inaccurate understanding of motives should find and read The Borax Conspiracy. We have to turn back the clock and learn that recently, some aspects of nutrition have been plagued by a determined misrepresentation of facts by actors that place profit before their humanity; to the long term detriment of human health.

Back in the 1940’s here in the UK, George Henderson, in two books, The Farming Ladder and Farmers Progress, showed how he felt that the ideal farm size was ~200 acres and his methods, (he and his brother bought their farm in the 1920’s), showed how they increased their income from ~£5 per acre to £250 per acre using integrated use of their own fertilizer inputs to the soil, rather than vast quantities of artificial fertilizer. For example their 96 Tons per acre yield of Mangels to feed their own stock. We have to learn to look back to past success, as well as to ongoing research, if we, as a species; are to survive over the very long term.

20th April 2018 at 5:32 pm

…Just to finish off a good story, if by any reasons your bread deteriorates and goes bad, do not through away as garbage for bursting landfills. Buried in the ground to enrich your soil with carbon and complete the cycle. Even better feed the red worms with it to generate the best compost there is.