By Tom Measham, Senior Research Scientist and David Fleming, Research Economist

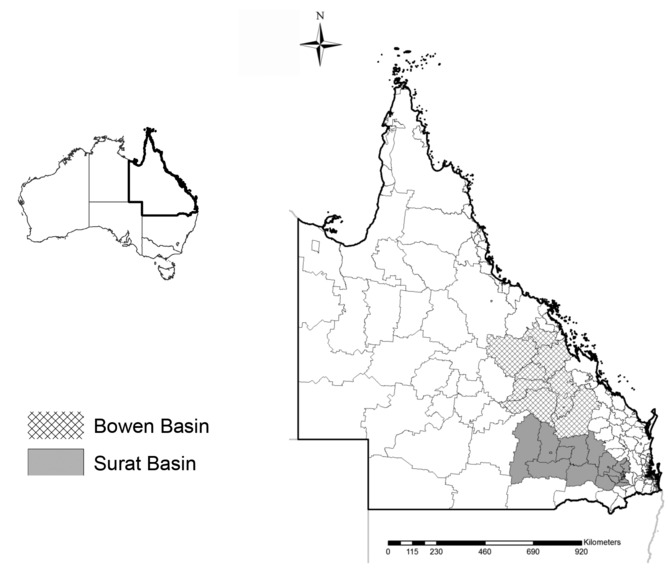

Why would young Australians buck international trends and move to the country? According to our research, a growing youth population has been observed in coal seam gas (CSG) development areas within the Surat and Bowen Basin regions of Queensland in recent years.

In contrast to other rural areas of Queensland, where the youth population is not growing, those two regions taking in areas such as Chinchilla and Moranbah have seen their youth population grow.

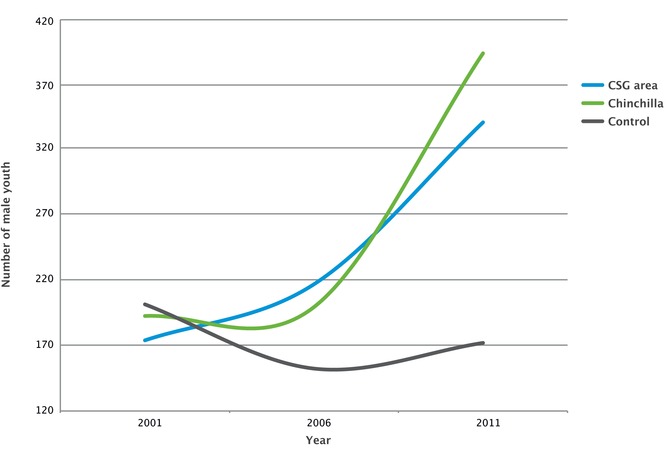

For example, in Chinchilla there were 1,112 young people aged 15 to 29 years old in 2006; just five years later, the number of young people had increased by about 46% to 1618. Out of that total, the male youth population in Chinchilla jumped 53% (to 978 young men), while the female youth population rose by 36% (to 640 young women).

This noteworthy increase in rural youth – for both men and women – is also seen in the broader regions of the Surat and Bowen basins, where CSG development is happening.

Figure 1. Regions in Bowen and Surat basins, Queensland.

Over the same period, family incomes have grown and overall employment has increased.

However, in studying the impacts of unconventional gas development, the one negative trend we found was that agricultural employment had decreased more than the rest of rural Queensland during the expansion of the coal seam gas industry.

A re-injection of youth

Declining populations in rural regions is a worldwide phenomenon. That’s because young people are usually the first to leave, seeking employment, training and education opportunities in cities.

After gaining new skills and experience, 20-somethings tend to stay in urban areas rather than return to their rural homelands. And women are more likely to leave rural areas than men.

The combined impact of these trends is a reduction in the skills base of rural areas and a skewed population, with more older people and far more men.

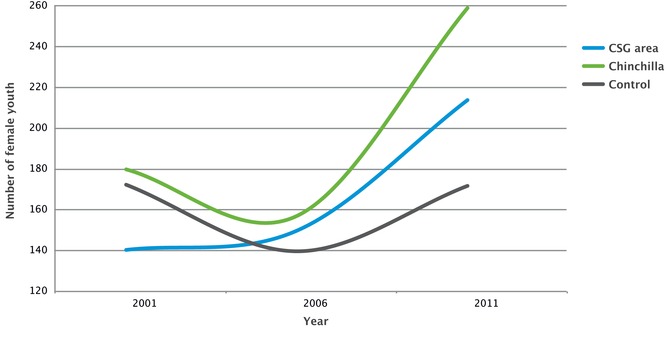

In figures 2 and 3, we track the age group which was 15-19 in 2001 though time up until 2011. In the control group, which is made up of other comparable rural Queensland regions (dark grey line), the youth population is at its lowest when this group hits their early 20s. By contrast, for communities in coal seam gas areas (blue line) the youth population is increasing throughout their 20s as more people stay in the region and others come to the region as CSG development takes off.

Figure 2. Changes in female youth over time (ABS 2013). The blue line is the average for towns and communities where CSG development occurs. The dark grey line is the average for regions without CSG development (control). The green line represents Chinchilla.

Figure 3. Changes in male youth over time (ABS 2013). The blue line is the average for towns and communities where CSG development occurs. The dark grey line is the average for regions without CSG development (control). The green line represents Chinchilla.

We’ve singled out the case of Chinchilla (green line) as an example of a turn-around in about 2006 from losing young people to gaining young people as the pace of CSG development speeds up.

Because these increases occurred in male and female populations, the research suggests that the wider rural population are experiencing social and economic benefits from the CSG sector, rather than just a male workforce commuting from distant cities, as can happen with fly-in fly-out workforces in other contexts.

The fact that rural youth populations have grown in regions with CSG development is a significant finding and an important contributor to the health of rural communities.

In terms of the long-term future of rural communities,re-injection of youth may indeed be more important than the focus on jobs, which has traditionally been the main way that the industry has sought to demonstrate its benefit to rural communities.

More jobs in resources sector, but fewer in agriculture

Our research also found that jobs have increased in regions where CSG development has occurred.

During the ten years between 2001 and 2011, jobs in the resources sector across rural Queensland increased; notably this increase was about 31% more in CSG regions than in other rural Queensland regions. This figure is even higher when looking only at the Surat region, where it has grown by 45%.

For every new job in the resources sector there has been around two new jobs created in the related sectors of construction and professional services. By contrast, for each new job in the resources sector there has been a reduction of 1.7 jobs in agriculture.

These new jobs in CSG areas are not just restricted to males. Focusing on Chinchilla, total female employment increased 26% from 1204 in 2006 to 1516 in 2011. Over those five years, women left some agriculture and manufacturing jobs, but increased their employment in mining, construction and hospitality.

Family income and community welfare

Another important finding is that family income has increased more in regions where CSG development has occurred.

Family income increased by around 15% in the average region with CSG development when compared to other rural regions in Queensland. Family income is a useful measure of benefit because it provides an indicator of income that stays in the region, compared with other measures that may be affected by long-distance commuting workforces, who spend their income elsewhere.

However, while family income is up, this also has to be balanced against higher housing costs in some CSG regions such as Chinchilla.

We found that CSG regions had slightly more educated populations, but mostly among men. Poverty reduction was also observed in CSG regions, concentrated particularly in Chinchilla.

Finally, it is also important to consider the impacts of CSG development on other aspects of community well-being, such as noise and stress. These issues are currently being explored in related projects conducted by CSIRO.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. Read the original article.

2nd May 2018 at 4:52 pm

Short term gain for long term environmental desecration.

20th October 2014 at 11:30 pm

The headline should be: “for each new job in the resources sector there has been a reduction of 1.7 jobs in agriculture”

That kills the idea of co-existence right there!

5th October 2014 at 1:28 am

When are CSIRO going to update the information. The young people are all leaving again as the projects are being completed and they’ve gone back to their homes on the coast.

Very misleading article. Shame.

23rd July 2014 at 7:52 am

Maybe the csiro would like to update this chinchilla rubbish as there are now well over 200 rental properties vacant. At anything up to ten people living in each of these hot bed properties I believe this data is now totally misleading to the public the csiro had a history of serving. A hot bed property is a property where the night shift climb into a bed vacated by the day shift for those who do not know.

17th January 2014 at 4:44 pm

Thats all well and good – but try the harder research how is coal seam affecting the aquifer and also ground water