An autonomous torpedo shaped underwater glider has just completed a trip through the eastern waters of the Great Australian Bight, collecting valuable data on the ocean.

74 days at sea. Gliding beneath the gentle ocean waves. Oh the serenity.

An IMOS ocean glider, Image credit - Australian Institute of Marine Science

An IMOS ocean glider, Image credit – Australian Institute of Marine Science

Wrong.

An autonomous torpedo shaped underwater glider has just completed this trip, and it has the battle scars to show for it.

On its journey through the eastern waters of the Great Australian Bight the glider traversed 1,800 km of the sea, collecting data on temperature, salinity and other variables from the ocean surface to a depth of 1,000 metres. The Integrated Marine Observing System (IMOS) ocean glider made 344 dives, surfacing regularly to transmit data by satellite back to land where oceanographers have been analysing the data.

On at least one dive the glider was attacked by a shark. Bite marks and a damaged oxygen sensor provide evidence the yellow object was mistaken for food and preyed upon.

Or was the shark just trying to protect the secrets of the deep!?

Together with IMOS, our oceanographer Dr David Griffin has been tracking the glider’s mission, mapping the route and data during its travels.

This animation shows the path taken by the glider across the Great Australian Bight. The panels at right scroll through some of the data collected from the surface to 1000m. Source: IMOS OceanCurrent

“Data collected from the glider will help us better understand how and why the Bight’s ocean waters move, both horizontally and vertically”, said Dr Griffin.

Through the collaborative Great Australian Bight Research Program, we are working with South Australian Research Institute (SARDI) to investigate the currents that flow on the continental shelf and the deep shelf slope in the Bight. The summer upwelling in the eastern Bight is also important as it brings nutrient-rich waters to the surface.

When this water reaches the sunlit zone, it provides the perfect environment for the growth of tiny ocean plants known as phytoplankton. These plants are the base of the food web that extends from tiny marine creatures through to apex predators such as seals…but thankfully not gliders!

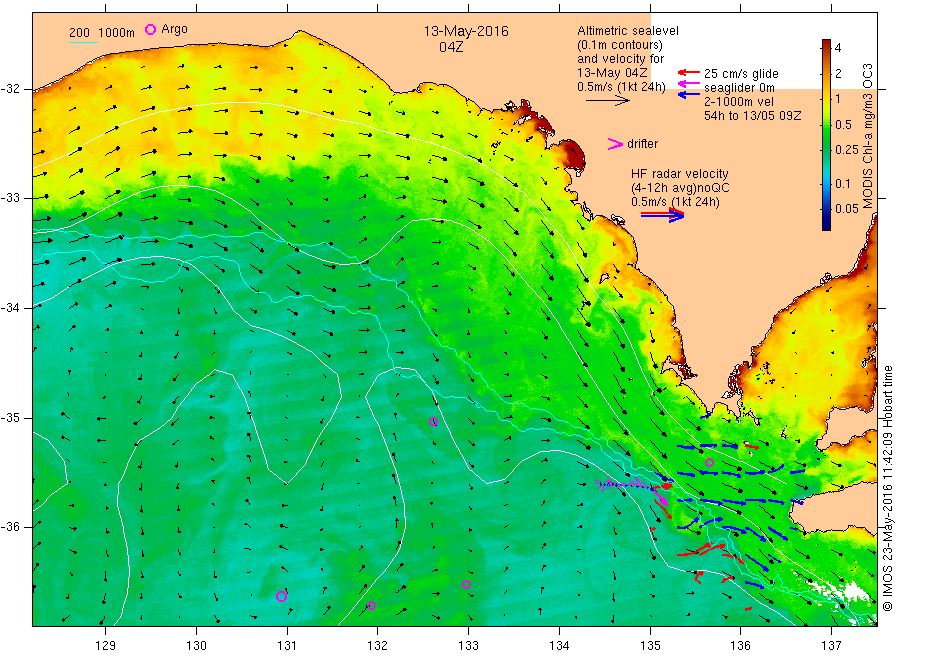

NASA MODIS image showing the chlorophyll concentration in the surface waters on 13 May 2016 towards the end of the glider mission (see glider at bottom right). Chlorophyll concentration is an indicator of the abundance of phytoplankton in the near-surface waters. Images such as this one help oceanographers interpret the detailed data from the glider. Source: IMOS OceanCurrent

NASA MODIS image showing the chlorophyll concentration in the surface waters on 13 May 2016 towards the end of the glider mission (see glider at bottom right). Chlorophyll concentration is an indicator of the abundance of phytoplankton in the near-surface waters. Images such as this one help oceanographers interpret the detailed data from the glider. Source: IMOS OceanCurrent

Information collected from the glider may also help to understand the relationship between waves and ocean circulation.

“Compared to other regions around Australia, the Great Australian Bight has stronger waves but weaker currents, so we suspect that the influences of waves may be more important for the marine ecosystem here than elsewhere,” said Dr Griffin.

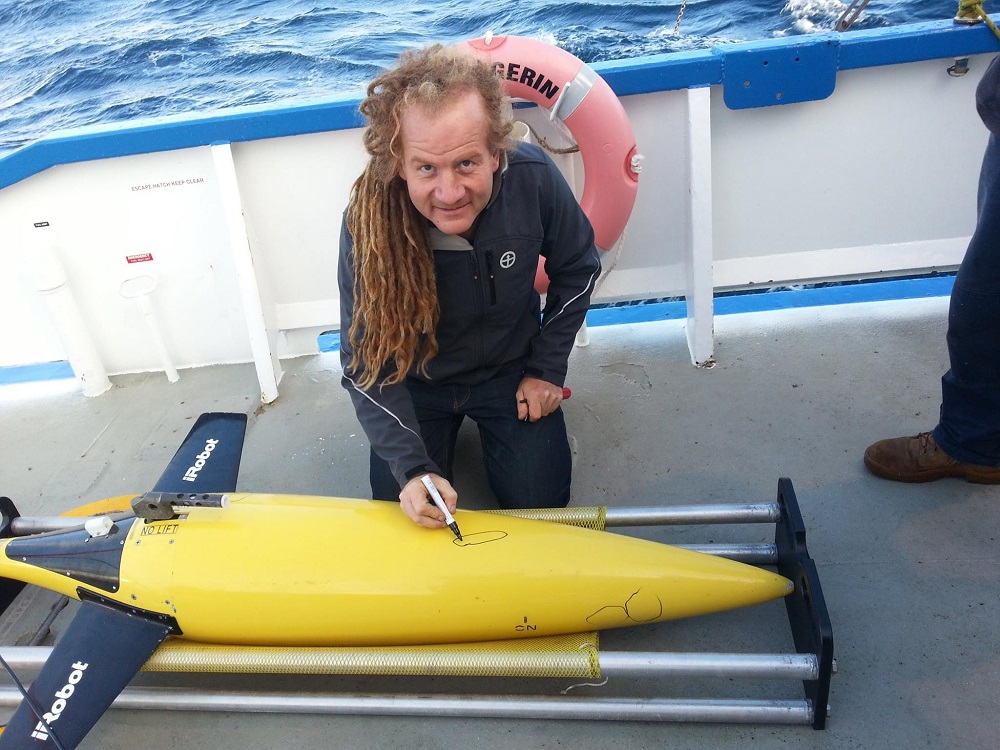

Ocean glider recovered after South Australian mission shows evidence of shark bite. Image Credit - Dennis Stanley, UWA.

Ocean glider recovered after South Australian mission shows evidence of shark bite. Image Credit – Dennis Stanley, UWA.

“Data from the glider and other similar missions is helping CSIRO and SARDI to understand how the Bight’s ocean waters move, and we now have more confidence that our numerical models can be used across the whole region to simulate some of the ecological processes.”

This project is part of larger efforts across the Great Australian Bight to further understand this unique marine region helping to inform decision makers and ensure future developments co-exist with the Bight’s environment, industries and community.

Find out more on our ocean research here.

The mission was part of the Great Australian Bight Research Program (GABRP), a collaboration between BP, CSIRO, the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI), the University of Adelaide and Flinders University. This four-year, $20 million research program aims to provide a whole-of-system understanding of the environmental, economic and social values of the region; providing an information source for all to use.

13th July 2016 at 3:46 pm

No doubt about it, a lot of technology contained in a small package, and functioning successfully in a hostile environment. Did it require servicing or guidance at times?

Frank La Fontaine

14th July 2016 at 10:57 am

It can’t be serviced mid-mission, but guidance is certainly possible. If something goes wrong (e.g. battery voltage falling faster than usual, as on an earlier mission), we tell it to come home. For this mission, it mostly just followed its pre-programmed set of waypoints using autopilot. In regions of stronger currents, however, it’s much harder to execute a planned mission using autopilot so daily decision-making by the mission operators and the project scientists is required.