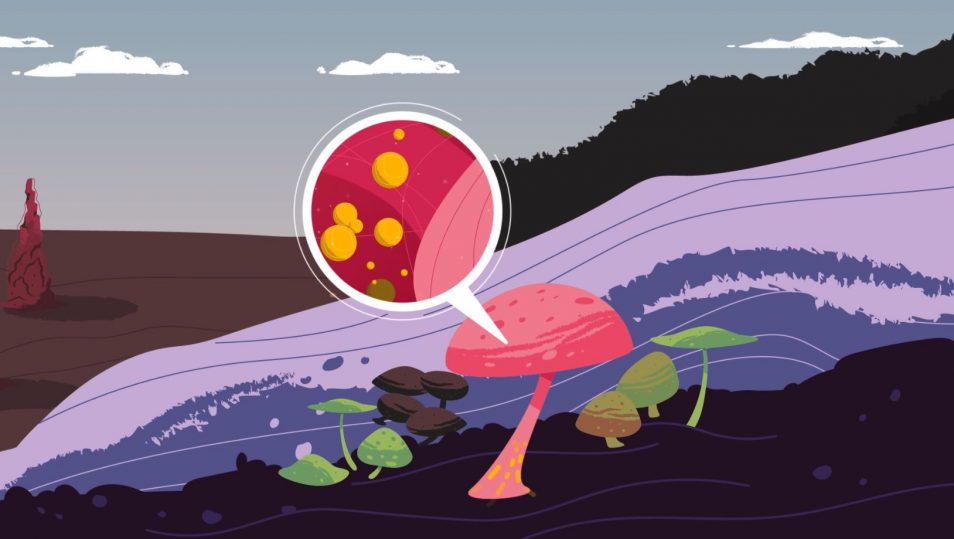

Is this a different type of magic mushroom?

Just last week, a Bendigo-based family struck gold by stumbling across a nugget worth $35,000 while walking their dog named Lucky. Lucky indeed, because such a prized find is rare – even on Australia’s gold-rich soils.

But there actually is a science to finding gold, and the ongoing modern-day search has led us to look in some bizarre and unlikely places.

Take our latest breakthrough, for example, where our scientists have discovered gold-coated fungi near Boddington in Western Australia.

Not to be mistaken with gold-capped mushrooms, this pink-flowering, thread-like fungi known as fusarium oxysporum is commonly found in soils around the globe

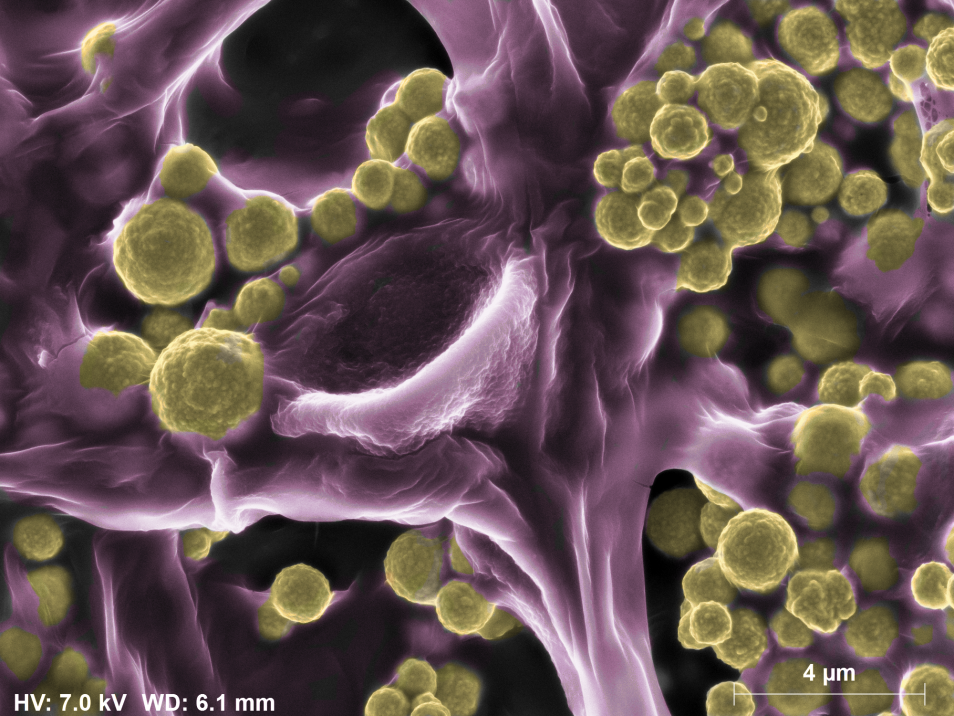

But if we zoom in on the fungi, it shows balls of gold fixed to its strands, much like baubles on the branches of a Christmas tree.

Fungi that’s fixated with gold

Coloured scanning electron microscope image of Fusarium oxsporium, which fixes gold balls to its strands, like baubles on a Christmas tree.

Our scientists discovered that the fungi attaches the gold to their strands through an oxidisation process – by dissolving and precipitating particles from their surroundings and fixing it to its threads.

And there appears to be a biological advantage in doing so.

Intriguingly, our scientists found that the gold-coated fungi grow larger and spread faster than those that don’t interact with the gold.

They also play a central role in a biodiverse soil community, meaning that the gold-coated fungi play host to a more diverse range of fungi, compared to those that don’t.

But hold your horses. Before you go out looking for fungi know that the particles of gold can only be seen under a scanning electron microscope.

Linking gold-coated fungi with a deposit below the surface

The research, published in Nature Communications, is the first evidence that fungi may play a role in the cycling of gold around the Earth’s surface.

While we don’t yet know why the fungi is so attracted to the gold, there is hope that it’s an indication of a deposit metres below the surface.

This may mean that fungi – and their functional genes – could be added to a growing list of nature’s clues at the surface that can be used to find gold underground.

Another example of this was we discovered that gum trees draw up tiny particles of gold via their root system and deposit them in their leaves. The exploration industry has had recent success hitting gold targets by sampling gum leaves.

Similarily, termites and ants are known to harbour gold in their mounds, which also has proven to be a useful indicator for explorers.

Adding fungi to the explorers tool-kit

Gold is an important export commodity for Australia – we are the world’s second largest gold producer today. But while gold production hit record peaks in 2018, forecasted estimates show that production will decline in the near future unless new gold deposits are found.

That’s why new, low-impact exploration tools are needed to make the next generation of discoveries and tackle the challenge of ensuring the world has a sustainable supply of resources.

We’re seeking to engage with Australia’s exploration industry to help us further this research and potentially develop an innovative fungi tool to lead the next generation of discoveries.

But, there are wider applications for this science too. Our scientists believe fungi could be used as a bioremediation tool to recover gold from waste.

Our discovery was made possible thanks to collaboration with the University of Western Australia, Murdoch University and Curtin University. The research involved a multi-disciplinary approach harnessing geology, molecular biology, informatics analysis and astrobiology.

To request a transcript please contact us.

3rd March 2020 at 1:04 pm

Species name typo, should be Fusarium oxysporum

10th March 2020 at 11:58 am

Thanks for letting us know Lam! We have updated this.

Georgia,

Team CSIRO