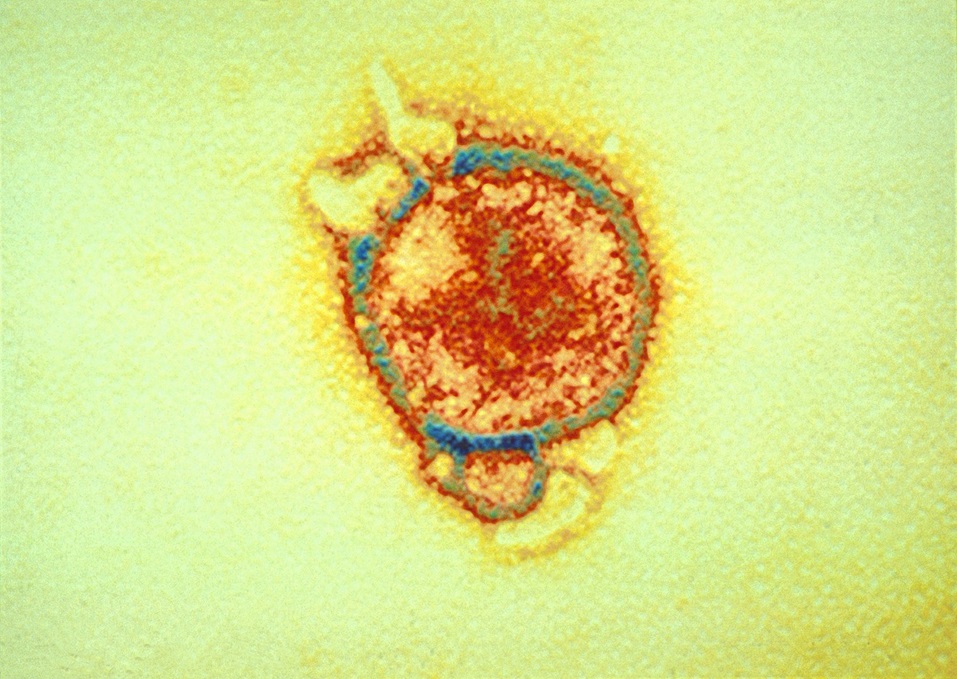

Electron micrograph of Hendra virus.

Infectious diseases kill more than 17 million people a year around the world. That’s a heavy statistic to picture. Billions more get infections from viruses, bacteria and parasites, and animal and plant infections add an extra layer of threat to our security and our environment. Diagnosing infectious diseases early and accurately is key to reducing their impact.

But there’s a problem: with current technology, many diseases can’t be detected until the late stages of infection.

Like trying to find Wally in a candy cane warehouse

Let’s look at an example.

Say Bob has been infected with a virus. There’s an incubation period for Bob before the disease kicks in, and during that period the viral particles will steadily increase in his system – but there still might not be enough for our current technology to spot them in his blood or bodily fluids yet.

Bob might get a false negative test result, just when it’s most important to detect the infection so it can be treated or prevented from spreading to others.

So it’s crucial we find ways to improve early detection of infectious agents, so we can provide timely treatment to heal people and timely biocontainment to stop diseases spreading further.

In the case of Hendra, it’d be fantastic to test a horse for the disease before it even becomes infectious or shows signs of the disease.

Fortunately, our scientists are working on that.

Researchers David Williams, Chris Cowled, Christina Rootes, Andrew Bean, and Cameron Stewart are working on finding a solution.

An early warning signal: from the horse’s mouth, er, molecules

Our researchers Cameron Stewart, Chris Cowled and Andrew Bean, based at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory in Geelong, Victoria, have been studying the Hendra virus. Carried by local flying foxes, the virus can be lethal to people and horses.

So far, every human Hendra case has come from contact with infected horses. But infected horses don’t actually show signs of the virus (such as elevated heart rates or temperatures) until the virus is advanced enough to be found in their bodily fluids – so horses can potentially spread the disease to people before tests can show they’re infected.

But our scientists’ new study, which has just been published in Scientific Reports, has shown promising signs of identifying an early warning signal of Hendra virus in horses – signs we’ve never seen before.

Rather than detecting the virus itself, our researchers measured levels of microRNA molecules produced by horses in response to Hendra virus infection.

MicroRNAs are small RNA molecules that can be readily measured in bodily fluids such as blood, semen or urine. We found that horse blood contains more than 700 different microRNAs, and when a horse is infected with Hendra, about 5 per cent of those molecules display an altered profile.

What happens next?

This finding, while promising, needs more testing on a larger scale to see whether the response is unique to Hendra virus.

If it is, it could potentially be used to develop a test that could detect Hendra in horses much earlier than our current tests allow.

Such a test could be useful, not as a replacement for existing tests but as an early warning to quarantine a horse. For instance, if there was an outbreak of Hendra on a property, neighbours could possibly test their own horses for an early indicator of whether the virus had spread, and to improve quarantine measures. Or it could be used to test horses planned for transport, to prevent other horses or even humans being exposed to potentially infected animals.

How microRNA profiles change in response to health status may represent a signature response that could be used to spot pre-clinical disease in humans and other animals.

29th August 2017 at 8:51 am

See articles on immune-RNA

14th August 2017 at 8:54 am

What would really be useful is if the test ends up being in a format that horse owners can use themselves, seeing as vets are so reluctant to come anywhere close to anything that reeks of Hendra. That way you could test your own horse (or at least take your own sample in a standardised way) if a vet won’t come out to your property.