Have you got questions about jellyfish? We've got answers (and some good tips to help you avoid the sting)!

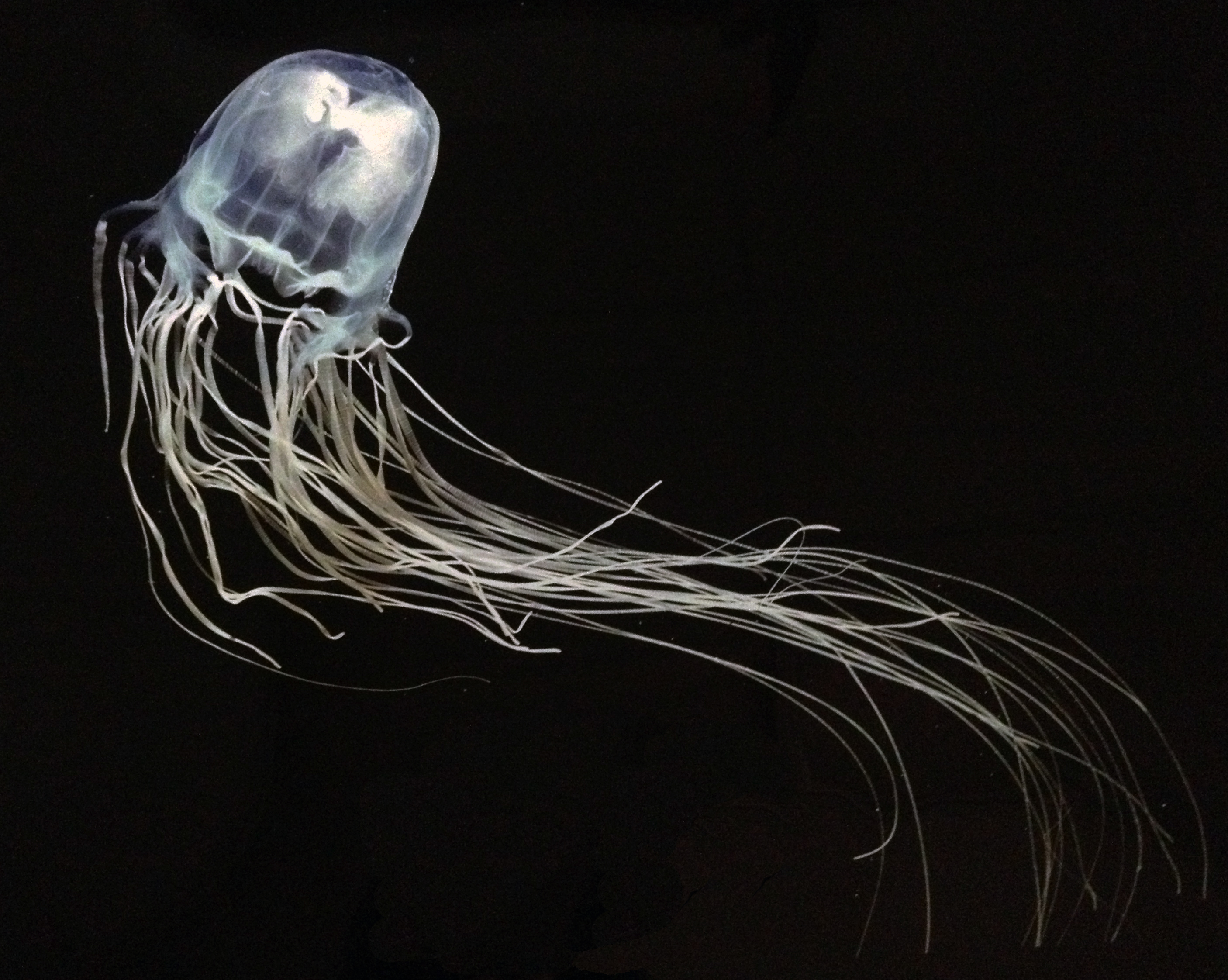

Chironex fleckeri (box jellyfish) Photo by Dr. Robert Hartwick

Chironex fleckeri (box jellyfish) Image – Dr. Robert Hartwick

What’s the difference between a box jellyfish and an Irukandji? Quite a bit really! Do jellyfish have brains? Short answer, no! Should I really get someone to pee on me if I’m stung? Also no: thanks a lot Friends!

If you’ve been plagued by these questions and can’t sleep at night because of it – don’t worry, we’re here to help with a little explainer on all things jellyfish!

Boxies and Hand-murderers

If you’ve been in Australia for longer than five minutes, then you’ve probably heard of the box jellyfish (if you’ve only just arrived, welcome to the land down under!). The box jellyfish (Chironex fleckeri) has four distinct sides (hence its name), and they’re most common throughout the tropics of the world. They can grow to be pretty big too – about the size of a man’s head – with up to 60 tentacles, each about two to three metres long. Chironex has the distinction of being the world’s most venomous animal – even its name suggests the hand of death: derived from the Greek `cheiro’ meaning `hand’, and the Latin `nex’ meaning `murderer’.

While their name and look isn’t very creative, the way that they sting is still pretty amazing. They have millions of harpoon-like microscopic stinging cells on their tentacles, each with a hair-trigger mechanism that injects venom into the victim. Worst case scenario you’ve got about two minutes until it’s all up – your heart will lock into a contracted state. In fact, their venom is the only thing in the natural world that can do that.

Boxies may be big, but Irukandji jellyfish (Carukia barnesi) are almost invisible to the naked eye. Irukandji contain a venom which, when injected into humans results in the following not-so-pleasant list of symptoms: excruciating muscle cramps in the arms and legs, severe pain in the back and kidneys, a burning sensation of the skin and face, nausea, vomiting, difficulty breathing, sweating, restlessness, headaches, a sharp increase in heart rate and blood pressure, and psychological phenomena such as the feeling of impending doom.

Irukandji jellyfish Image -

GondwanaGirl/Wikipedia

Carukia barnesi (Irukandji jellyfish) are very small and transparent. Image – GondwanaGirl/Wikipedia

Avoid the sting

It’s not all doom and gloom though as there some easy ways to avoid these painful stings:

- Swim at a patrolled beach: if there is a sign up telling you not to swim in the water because there are deadly jellyfish present, don’t swim in the water;

- For an extra measure of protection, get yourself into a full-body lycra suit – the stinging cells’ harpoons are really short, so if you’re wearing something that’s even a 10th of a millimetre thick, you’ll be better protected;

- If you do happen to get stung in the tropics, the Australian Resuscitation Council guidelines recommend dousing the sting with vinegar to neutralise the undischarged stinging cells.

Studying our stinging jellyfish

So, why should we study jellyfish at all if they’re so pesky and painful? Well, we don’t have a robust long term global data set because nobody really thought that jellyfish were very important. But it turns out that jellyfish blooms are causing all kinds of problems around the world: they’re stinging fisherman (and fish!), they’re eating the eggs and larvae of other species, not to mention getting sucked into power and desalination plant pipes and wreaking havoc with fisheries in many places, such as the Sea of Japan.

9th June 2017 at 3:15 pm

Interesting article! I was stung by what probably was a jelly fish at Cottesloe Beach in WA. From what I know though, we don’t really have any super toxic jelly fish. I had a welt on my stomach where I was stung. The following 24 hours were really tough. I had a fever, had trouble standing (dizzy and weak muscles) and my neck ended up really locked up. I could barely drive home from university that day. Is it possible a jelly fish floated down to the south of WA and I was just unlucky to encounter it? Or are there some jelly fish in the local waters which can lead to these symptoms?

6th June 2017 at 10:58 am

And after the vinegar, remove the tentacles. So the nematocysts don’t sting again. But vinegar triggers release more trouble in ordinary jellyfish, hey?