Knee deep in war, something extraordinarily progressive happened in Australia in 1916. Watch the speech, find out about the exhibition, and help us celebrate 100 years of Aussie innovation.

Volunteers at Federal Government House in St Kilda Road, Melbourne in 1916, the location of State Headquarters of Red Cross for some of the war years. The women were packing items to be sent in parcels to troops at the front. Courtesy Australian War Memorial, ID J00346

Knee deep in war, something extraordinarily progressive happened in Australia in 1916. In this image, Red Cross volunteers in Melbourne pack parcels for troops at the front. Image courtesy Australian War Memorial, ID J00346

Usually on this blog we ask you to think of tomorrow, to embrace and be excited about what sci-tech can do (and is doing) for our collective futures. Not today. Today, we’re asking you to step back in time – exactly 100 years ago to the Australia of 1916. Because at this time, a decision was made that has changed the course of Australian history – and made CSIRO what it is today.

Australia, 1916. The population was just about to tip five million, and life was hard. Australia was 18 months into a war on the other side of the world. Our losses on the Western Front were heavy and almost every family was affected in some way. There was a raging political debate about military conscription that was dividing our political parties. The cost of food and groceries had jumped 35 per cent in two years. There was a shortage of teachers (and paper) in schools. Life expectancy for both sexes hovered at 60 years.

And yet… the Sydney Conservatorium of Music welcomed its first students. Henry Lawson published the poem ‘Black Bonnets’ on his path to becoming one of our most revered poets and writers.

In science, William and Lawrence Bragg were awarded a Nobel Prize for their pioneering work in X-ray crystallography. And Headlie Taylor was putting Australian agriculture on the map with his mechanical inventions.

And so out of this time of hardship, the rough shape of Australian identity was forming.

It’s no surprise then what happened next.

Prime Minister Billy Hughes, looking to the future and to Australian prosperity, made a speech to Parliament that would have a fundamental impact on science and research forever:

To the rejection of shams, indeed! Apart from being an impressive and eloquent speech that we wanted to share, it also had a big impact on Australia’s future. It led to the founding of the Advisory Council of Science and Industry, a precursor to the CSIRO.

Without this speech and the eventual founding of the CSIR in 1926, there may never have been a national scientific agency in Australia. Think of all the things that would be missing in our world if that had been the case!

Wifi, we hear you exclaim. Yes, without CSIRO there may never have been wireless local area network (WLAN) innovation, the precursor to modern WiFi. And we’re not the only ones who think this is one of our most important achievements.

This week, it was announced that the National Museum of Australia in Canberra will be hosting a travelling exhibition from the British Museum – A History of the World in 100 Objects.

In its only east coast venue, 100 Objects will showcase items from around the globe to explore the last two million years of human history, sourcing the oldest objects from the British Museum’s collection and incorporating those from the present day.

The National Museum has chosen to include a 101st object representing a globally recognised Australian innovation. You guessed right – they’ve chosen WLAN.

The WLAN invention increased indoor wireless data transmission rates from 10 megabits per second (10 Mbits/s) to greater than 50 megabits per second (50 Mbits/s) and prevented the distortion of the signal, as the radio waves bounced off walls and furniture.

The story of the WLAN invention is a fascinating one because few people know it came out of our work in radiophysics.

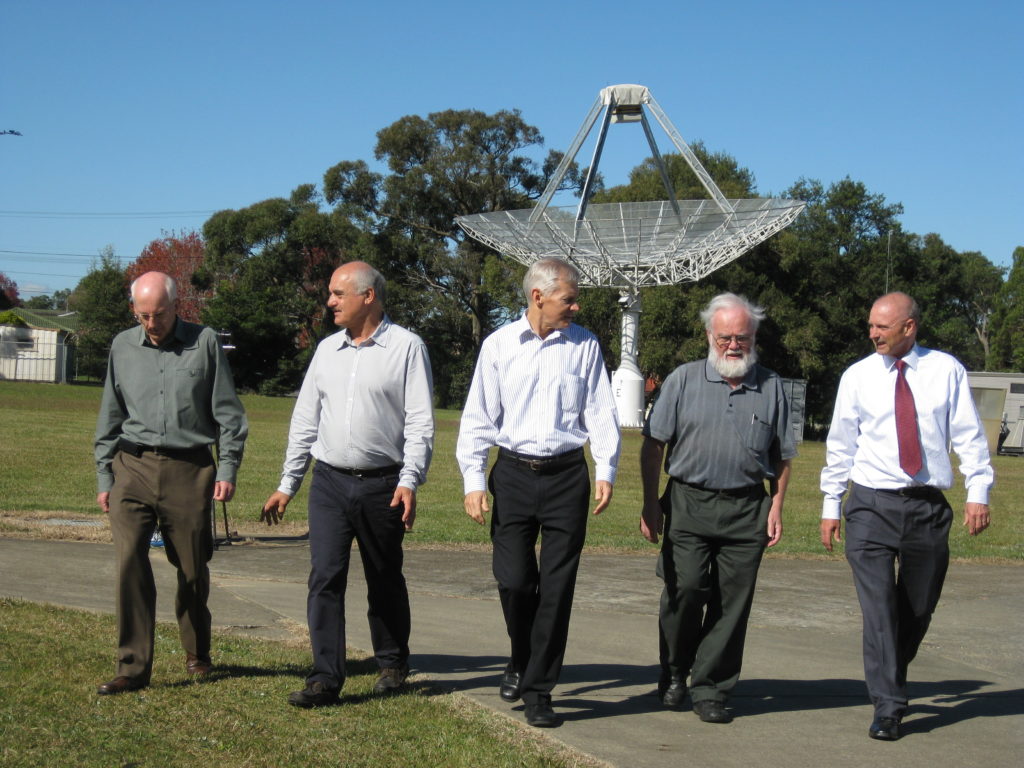

SIRO's WLAN team in May 2012. From left, Graham Daniels, Diet Ostry, Terry Percival, John Deane and John O'Sullivan.

CSIRO’s WLAN team in May 2012. From left, Graham Daniels, Diet Ostry, Terry Percival, John Deane and John O’Sullivan.

The 100 Objects exhibition opens on the 9th of September. You won’t want to miss it.

In the meantime, test your knowledge of yours truly with our short and sharp quiz… or treat yourself to a centenary t-shirt. We’re celebrating, after all.

29th November 2016 at 12:27 pm

A small comment – the article is great, however the Bragg’s were awarded the 1915 Nobel Prize for Physics and not the 1916 Prize – https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1915/index.html