This article originally appeared in The Australian.

Australians are great inventors: as a nation, we’re responsible for more than 100 great inventions, such as fast WiFi, ultrasound for medical imaging and the Cochlear implant. But of those, only one has built a great domestic tech company. This is our innovation dilemma.

It is easy to confuse invention and innovation. Invention can often be an individual achievement but innovation is always a team sport. Innovation is about taking an idea and realising the value — along with all of the sweat, tears and pain it takes to get there. And innovation happens best at the intersection of different disciplines and different ways of thinking. Collaboration is the fuel that drives it.

Herein lies part of our dilemma: Australia has the lowest level of research collaboration in the OECD. This is for two reasons: we don’t collaborate enough with business, and we actively compete against each other in science.

Thankfully, there is some good news. For one, we are so inventive, and invention is the wellspring of innovation. Even more important, we have the fourth largest funds management industry in the world, with $2 trillion looking for things to fund. But overall, our innovation dilemma — fed by our lack of collaboration — is a critical national challenge. (I applaud The Australian for allowing a platform to talk about it.) We must do better. Lucky then that CSIRO’s sole purpose is to solve national challenges.

After spending a quarter of a century in Silicon Valley, I learnt to share my ideas early and get feedback. Other entrepreneurs didn’t steal those ideas. They made them better. The value wasn’t in the idea, it was on the delivery. I started six tech companies, and the ecosystem I operated in supported me: from universities such as Stanford and MIT to venture capital funds such as Sequoia and Accel. When I stumbled, that ecosystem picked me up and encouraged me to go again. When I got lucky, that ecosystem made sure I paid it forward.

The most resounding reward in my first initial public offering was seeing how many millionaires our employee stock ownership plan created in our team. Those millionaires went on to found new companies and create more value. This is the virtuous cycle of innovation. It’s why start-ups created 100 per cent of the jobs growth in the US over the past 35 years.

This is the nature of an ecosystem of support and collaboration, where value is created by pure entrepreneurial alchemy out of a blue ocean. We can create a similar ecosystem in Australia, but first we have to stop clawing at each other for scraps and work together to create enduring value.

CSIRO must help the 41 universities of our nation to deliver impact from their great science and inventions. We must meet industry halfway, providing solutions, not just science.

This is critical because universities should not be forced to divert from fundamental research. We know from history the greatest inventions come from out of left field — ultrasound for medical imaging, the silicon chip, optical fibre comms, the router, WiFi and the internet itself all came from fundamental deep tech breakthroughs in areas far from the markets they created — markets that didn’t exist when they started.

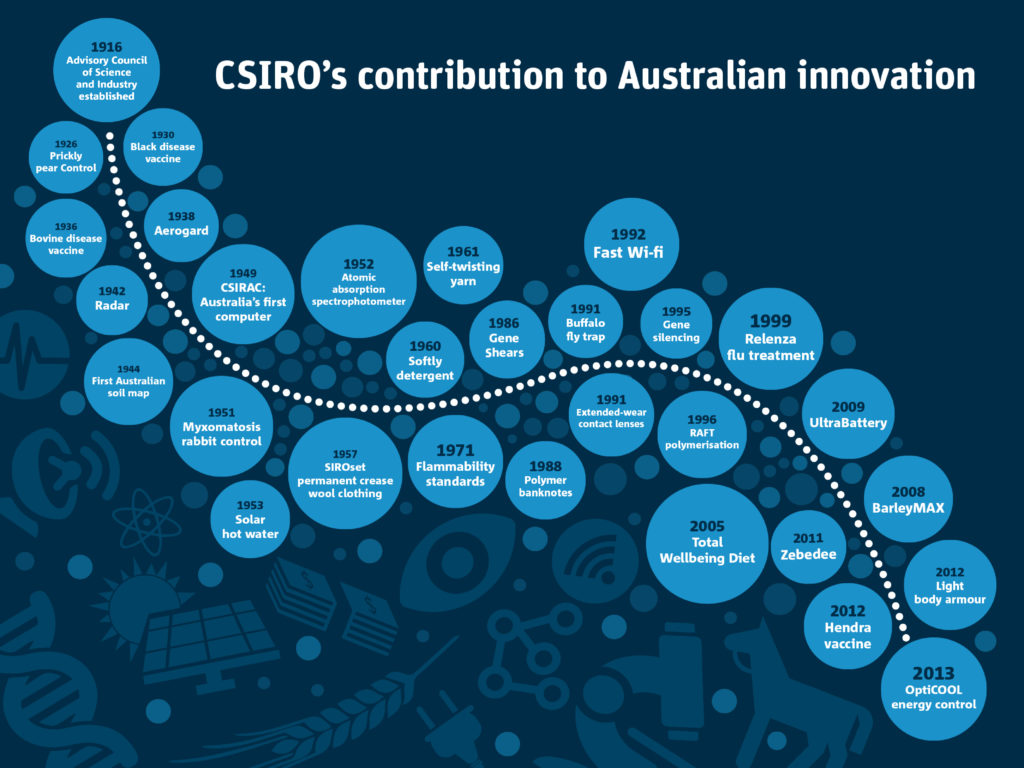

Almost 100 years of CSIRO innovation

While we at CSIRO are always looking how to solve problems, that capability will not always lie with us. When we collaborate great things happen: we helped professors at Macquarie University, in Sydney, create Radiata, Australia’s first WiFi company, and we helped Curtin University and the University of Western Australia create a global hub for metre-to-atomic-scale analyses of rock cores.

We helped the Queensland government, the University of Queensland and Griffith University create the urban water security research alliance to help address southeast Queensland’s urban water issues, and we helped Victoria’s Monash and Deakin universities 3D-print a jet engine.

People say CSIRO can be slow and cumbersome yet in 1942, isolated from the rest of the world by war and with no access to advanced technology or components, we created, in a matter of months, Australia’s first air-defence radar and defended Darwin. Innovation is hard; it’s meant to be that way. It’s what birthed the start-up nation, Israel. It’s what will transform Australia into a knowledge economy.

Most important, we provide a national platform to support science, technology, engineering and mathematics in schools through a unique volunteer network across publicly funded research organisations like CSIRO and the Defence Science and Technology Organisation, universities and companies like Cisco, BHP and Boeing.

We co-ordinate thousands of school visits to help our nation’s children better understand technology, maybe to pursue a career in STEM, to inspire them the way we were inspired by our teachers. Above all, to teach them that they can create our future.

Work with us to help solve Australia’s innovation dilemma. We partner with small and large companies, government and industry in Australia and around the world.

1st November 2015 at 8:39 pm

For the Innovation Challenge.

GIANT BATTERIES!!!

Can we drill hundred of holes into coal seams filling the holes with annodes.

Attach lighting rods or concider storage of clean energy.

What better use of coal that needs to stay in the ground.

Shaune.

7th September 2015 at 4:34 pm

Your message is definitely correct – great science, poor development.

“CSIRO must help the 41 universities of our nation …”, etc.

But it’s also individuals, businesses and government departments. For example BOM, Geosciences Australia, CSIRO, etc don’t seem to talk together. And who do individuals or small groups approach for help? Whose job is it to provide such coordination and encouragement?

I think CSIRO is in the ideal position.