The World Health Organization has confirmed the current outbreak of Ebola virus in Africa is the largest recorded outbreak, killing 672 of the 1201 confirmed cases since February this year.

So it’s no surprise that there’s increasing global concern about the spread of this virus – the situation is undeniably scary. Here’s what you need to know.

What is Ebola virus?

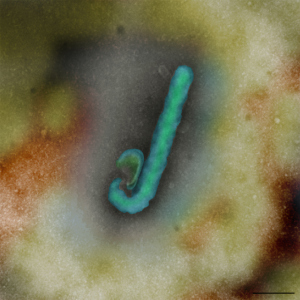

Ebola virus, also known as Ebola hemorrhagic fever, is a highly infectious illness with a fatality rate of up to 90 per cent. The virus is feared for its rapid and aggressive nature. Symptoms initially include a sudden fever as well as joint and muscle aches and then typically progress to vomiting, diarrhoea and, in some cases, internal and external bleeding. Contrary to Hollywood’s depictions, many people do not suffer massive and dramatic blood loss. They instead die from the shutdown of vital organs like the liver and kidneys.

Prior to this current situation, the largest outbreak of Ebola virus involved 425 people in Uganda, in 2000.

Ebola virus is a zoonotic disease – one that passes from animals to people. As with the respiratory diseases SARS and Hendra virus, bats have been identified as the natural host. There is good evidence to suggest other mammals like gorillas, chimpanzees and antelopes are most likely the transmission host to people but the way the infection passes to them from the fruit bats is still not clear.

Why is it called Ebola?

The virus was first discovered in 1976, with two simultaneous outbreaks of the disease – one near the Ebola River in Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of Congo), and the other in Nzara, Sudan. Since then more than 1600 deaths have been recorded.

How does the virus spread?

The virus is transmitted from wild animals to people. It can then spread through contact with bodily fluids from someone who is infected, or from exposure to objects like contaminated needles. People most at risk include health workers and family members or others who are in contact with the infected people.

Are there any treatments available?

There is no vaccine or known cure for Ebola virus infection. As with many emerging infectious diseases, treatment is limited to pain management and supportive therapies to counter symptoms like dehydration and lack of oxygen. Public awareness and infection control measures are vital to controlling the spread of disease.

What is CSIRO doing?

We have been researching the Reston ebolavirus strain, which is endemic in parts of Asia, for several years at the Australian Animal Health Laboratory (AAHL) as part of our mandate to study new and emerging infectious diseases to ensure we’re prepared should they ever reach Australia.

In 2013, following approval from the Australian government, we imported several Ebola virus isolates including the Zaire ebolavirus strain from Africa for research purposes. We’re investigating the pathogenicity, or disease causing ability, of these viruses, to understand why the African strains have a high fatality rate in people, compared to the Asian strain, which does not cause human disease.

There are strict international protocols, government approvals and security measures in place to ensure such viruses are transported and imported safely. At AAHL, all work with Ebola viruses is at the highest level of biocontainment, deep within the facility’s solid walls. Our specialist staff must work on the virus wearing fully encapsulated suits with their own external air supply.

Although most of our research is in cell and tissue culture, in the coming weeks our scientists plan to work with ferrets, which have shown human-like responses to infection with other high-risk pathogens, to understand what makes the Ebola virus pathogenic. We believe that understanding the differences in virulence between the two closely related strains of Ebola may hold the key to developing an effective vaccine to prevent this deadly disease, or therapeutics to treat it.

Why is CSIRO involved in the global response to fight this deadly disease?

AAHL has highly specialised capabilities for working with zoonotic diseases. Scientists at AAHL first identified and characterised the deadly Hendra virus, which, like Ebola viruses, is classified as a ‘biosafety level four (BSL4) pathogen’- the most dangerous of viruses, without a known cure or vaccine. The team has since been integral in the development of the Equivac HeV vaccine, now being administered to protect horses and people in Australia.

Located in Geelong, AAHL is one of a handful of high-containment laboratories in the world capable of working on BSL4 pathogens. The facility was built to ensure the containment of the most infectious agents known. It is designed and equipped to enable the safe handling of disease agents such as Ebola virus, at the necessary high containment level.

For more information about the Ebola virus, see the World Health Organization fact sheet.

6th August 2014 at 8:55 am

Do antibodies developed from infection by the relatively harmless Asian strain confer any immunity against the more harmful strains?

7th August 2014 at 11:34 am

It would seem not. The only known attempts to test this hypothesis returned inconclusive results. Not surprisingly it would be hard to get ethics committee approval for a large-scale trial.

6th August 2014 at 2:17 am

¡Gracias por la información, como bibliotecaria del área clínica les reenviaré a los médicos este artículo en especial a los infectó logos. Espero seguir recibiendo vuestros artículos

Norma Monterrey Caro

5th August 2014 at 4:52 pm

I can think of no stronger argument for investing in research than the Hendra / Ebola story. Ebola was discovered in the 1970’s yet we know so little about it. Hendra came out in 1994 nearly 20 years later and we appear to have a far better understanding of what it is, how its transmitted and how to deal with it. Clearly 2 different viruses very much an apple vs pear argument but I can’t help but wonder what would have happened if in 1994 Ebola had been found in Australian fruit bats.

5th August 2014 at 3:16 pm

Could you please give a description of the virus at the molecular level. Clinical information is media-worthy but scientists should have some of the insight available from the ICTV reports.

5th August 2014 at 5:05 pm

It’s a ssRNA negative-strand virus with a genome about 19kb.

virus genome sequencing project:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioproject/PRJNA257197

partial genome sequence data example for recent outbreak:

http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/KM233035.1

look in genbank for accession: KM233035

5th August 2014 at 5:19 pm

Thanks, Keith. Appreciate your assistance. I was busy on something else and hadn’t had time to find out more answers.

4th August 2014 at 4:02 pm

Nice story and best of luck with the vaccine, but you need to find out more about the way people in west Africa live out in the villages. A mining friend of mine returned to Australia last year after 20 years living in Guinea and Ghana. He tells me every village in Guinea has a big mango or fig tree at the centre of town. Under this big fruit tree is where people gather to meet, greet and eat. Unfortunately this is also where lots of fruit bats also gather to meet and eat, dropping their faeces and urine down on to people below. Get the picture? Another example, this time in the capital Conakry, would be taxis. My friend used to travel by taxi a lot. The driver would always wait until the taxi had as many people crammed into it as possible before moving off. Pretty good if you enjoy close personal contact with strangers.